Pushing for a Just Transition: Plains Tribes Versus Big Energy

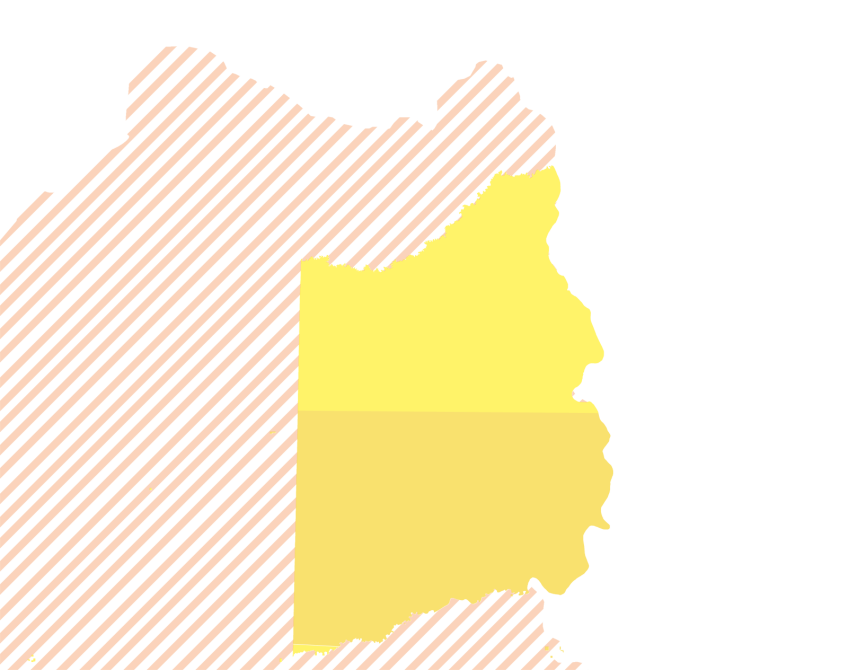

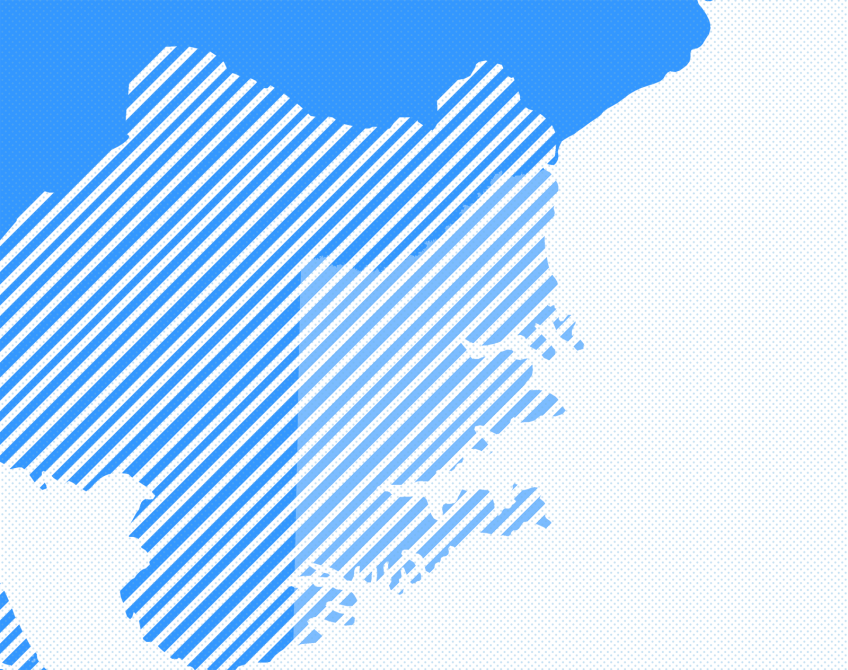

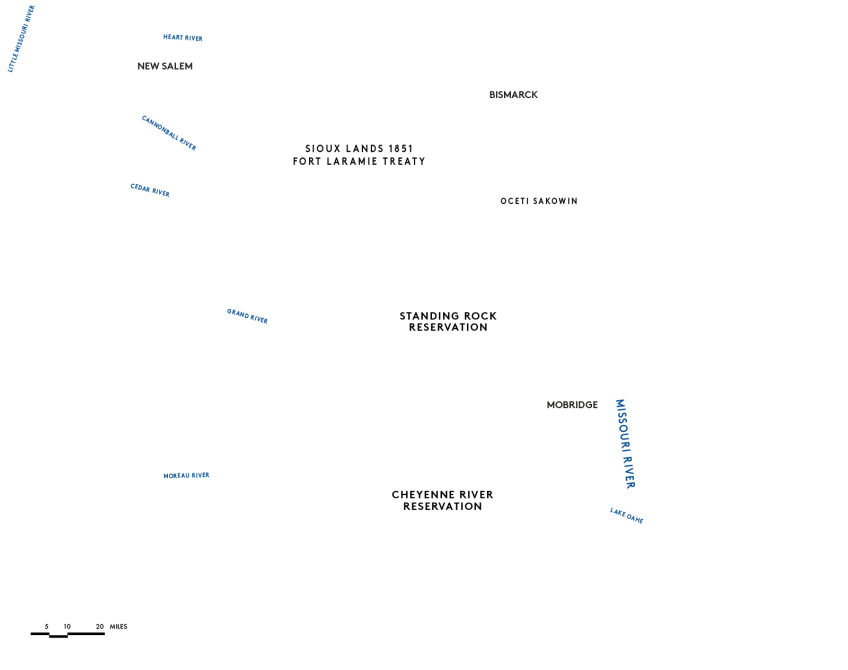

Last year, the Dakota Access pipeline became a rallying cry for the Indigenous rights and environmental movements. Members of hundreds of tribes descended on the Standing Rock Sioux reservation in North Dakota, and thousands of allies joined the cause to stop completion of the 1,172-mile pipeline, calling attention to impacts on the land, water and climate, as well as on sacred burial grounds.

Though the water protectors celebrated defeat of the pipeline in December, President Donald Trump gave the project the green light shortly after taking office. Current lawsuits notwithstanding, Energy Transfer Partners, the company behind the project, expects to begin interstate oil delivery on May 14.

The Dakota Access Pipeline is just one, albeit high-profile, example of the ways in which energy development impacts Native communities in the Great Plains region. In the case of the Standing Rock Sioux, the tribe says it was not adequately consulted for a project that was rerouted from a majority-white community to pass through historical Sioux lands, and expresses deep concern that the pipeline will jeopardize the Missouri River, under which it passes.

The pipeline’s potential impacts extend to other tribes as well.

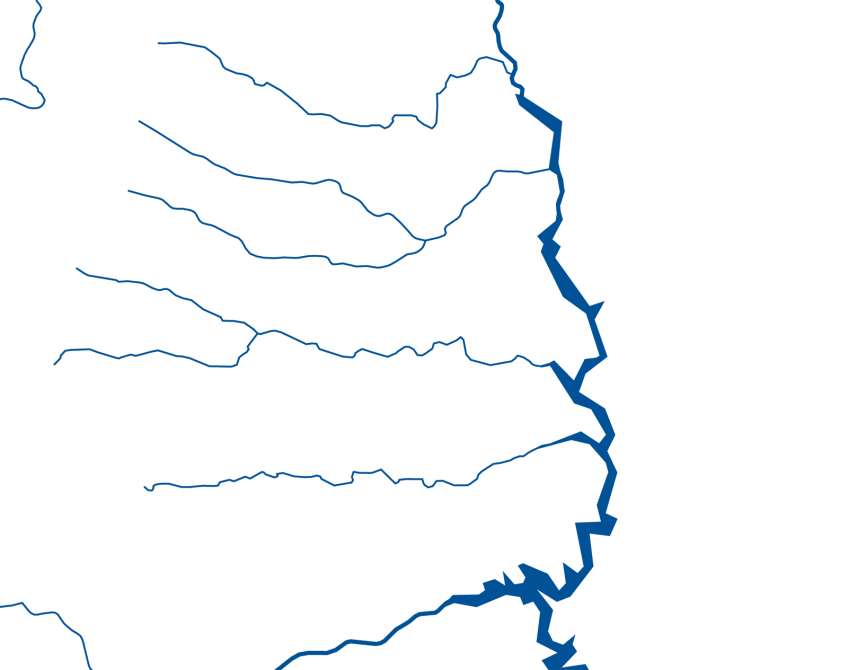

Research by Jennifer Veileux, of Florida International University in Miami, documents nine places where the Dakota Access pipeline crosses major rivers or streams in the Missouri River watershed, which means there are at least nine major places where an oil leak could contaminate that watershed. What’s more, she found that a pipeline failure could threaten the land of no fewer than 13 tribes along the route.

In other cases, the impacts of energy development on Native communities stem less from the transport of oil and gas near Native lands, but from extraction itself. Estimates vary as to exactly how much fossil fuel lies below Indian reservations, but by some calculations, nearly a third of all coal reserves west of the Mississippi River are on Native lands, in addition to twenty percent of known US oil and gas reserves (and 50 percent of potential uranium reserves). And though only a small percentage of American fossil fuel production currently takes place on Native lands, reservations in Wyoming, Colorado, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, Montana, Oklahoma, and New Mexico sit on substantial reserves. This includes parts of the Bakken oil play in North Dakota and Montana, from which the Dakota Access will soon begin transporting oil.

In North Dakota, the development of these resources — part of which has been undertaken by the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation, also known as the Three Affiliated Tribes — has had far-reaching impacts on Native communities.

“It was and has been very negative from my perspective,” says Kandi Mossett, lead organizer with the Indigenous Environmental Network’s Extreme Energy and Just Transition campaign and a member of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation, referring to the impacts of the shale boom that began in 2008. “The impacts have all been horrific.”

She points to a range of social, environmental and health effects, including everything from an increase in sex-trafficking, to a spike in drug use, to growing violence against women.

“What I’ve seen is that when destruction of the earth happens… inevitably violence against the people happens… especially in the small rural communities that exist in North Dakota,” Mossett says.

Local infrastructure has also been over-burdened. As workers poured into the region, local schools were packed with new students, existing housing shortages were exacerbated, and roads literally crumbled under the pressure of the semis that rumbled through town. Mossett herself first began pushing back against the fracking industry when a friend was killed by one of these trucks nearly a decade ago.

Effects are felt across the region, but Mossett thinks they are amplified on reservations. “The thing I’ve observed is that it’s even worse on the reservations because the lack of regulations is even more prominent,” she says, and services from medical care, to police forces, to rehabilitation facilities, “just don’t exist.”

Meanwhile, people are getting sick. Mossett says there’s been an increase in asthma, and cancer in her community, and indeed, fracking-related air pollution has been linked to a variety of serious health issues, including respiratory problems, blood disorders, birth defects, nervous system issues, and cancer. High levels of toxins have been found in the bodies of those living near fracking sites, and a recent study pointed to increased mortality in newborns in fracking-intensive regions.

Dr. Kerry Hartman, an environmental scientistat Nueta Hidatsa Sahnish College in North Dakota, has been studying the impacts of energy development on both air and water on Fort Berthold Indian Reservation. He’s documented several air quality issues in the area, including those related to flaring (the process of burning off gases that are released during the oil production process), which he describes as releasing a “cocktail of hydrocarbon compounds,” including methane, and benzene. He also points to particulate matter, noting that the combination of increased traffic and unpaved roads in the area have caused a lot of dust. Breathing in the dust-filled air is “similar to breathing in a dust storm,” he says.

Fracking has also been linked to water contamination, both from leaking wells and produced water spills, which is especially worrisome given that fracking is not regulated under the federal Safe Drinking Water Act. (Fracking is water intensive, and results in large quantities of highly saline wastewater.) Water contamination can impact drinking water, as well as local habitat, wildlife, and livestock. Indeed, Hartman’s research indicates contamination of several water wells on the Fort Berthold reservation (though he says almost everyone on the reservation is connected to the water treatment plant). A separate 2015 study on the impact of saltwater spills in North Dakota, conducted by a Duke University team, found that they had left behind a legacy of radioactive soils, polluted streams, and poor aquatic health.

Lisa DeVille, president of Fort Berthold Protectors of Water and Earth Rights and a member of the Three Affiliated Tribes, underscores this point. She says that the site of a massive 2014 saltwater spill near the Fort Berthold reservation town of Manaree has had “no recovery.”

We are protectors of the earth,” she says. “So to see all this happening to us, and living with it every day — living with the health impacts, living with the environmental impacts — it hurts very much.”

Of course, not all tribes or tribal members are opposed to fossil fuel development on Native lands. In North Dakota, the Three Affiliated Tribes have actively developed their fossil fuel resources, as have the Crow in Montana, the Southern Ute in Colorado, and the Navajo Nation, located at the intersection of modern-day Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico. These tribes have received significant revenue for fossil fuel leases on their land, money that pays for infrastructure improvements and is distributed to tribal members as royalty checks.

Among many of these tribes, and others, there are also those pushing for a just transition away from fossil fuels and towards renewable energy development. The Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians, for example, seeing the destruction wrought by fracking in Fort Berthold, passed a fracking ban back in 2011. And other tribes, looking to their ample wind and solar capacity, are turning toward development of renewable energy resources. (Though renewable projects, too, can carry their own perils.)

Mossett, for one, thinks renewables are the way to go. “The resources when it comes to oil and gas, they’re finite,” she says. “It’s like we’re playing this game of Russian roulette, and we’re trying to see what’s going to last longer. It’s a really stupid game to play.”

Energy extraction has already resulted in extensive damage to Native lands and sacred sites, not to mention the global climate. Given the vast fossil fuel reserves that still exist both on and off reservations, here’s to hoping that the just transition begins sooner than later.

Map Feature Currently Unavailable