Love California's Mountain Forests? You Can Thank The Gobi Desert

California has long been renowned for its amazing forests, especially those scattered groves of giant Sequoias on the west slope of the Sierra Nevada. But California's big trees might not be what they are without an important contribution from East Asia.

That's according to a study by researchers from UC Riverside and other universities, who found that a crucial plant nutrient missing from native Sierra soils is blowing in as dust from across the Pacific Ocean. The nutrient, phosphorus, is crucial for root development, and a deficiency often leads to stunted growth and general ill health.

Scientists have long known that trees growing on the Sierra Nevada's phosphorus-deficient soils were getting the nutrient from somewhere, likely from dust blown in from other parts of California. The range does indeed receive some California dust. But as it turns out, higher elevations in the Sierra Nevada get almost half of their inflow of dust from the Gobi Desert, astride the border between China and Mongolia, 6,200 miles upwind of Yosemite.

The researchers' results were published March 28 in the journal Nature Communications.

According to the study, the Gobi and other Asian dust sources supply from 18-45 percent of the available phosphorus in Sierra Nevada soils. Much of the rest comes from California's Central Valley, whose soils are increasingly loosed into the atmosphere as dust by agricultural activity.

The scientists used innovative, low tech equipment to collect dust being deposited on the Sierra Nevada: bundt pans filled with quartz marbles. The pans, whose rims were coated with a sticky substance to deter perching birds, were deployed on six-foot poles at four sites in the Central Sierra. Site elevations ranged from 1,300 feet to 8,800 feet above sea level. The collectors were deployed on several occasions for a month at a time.

One collected, the dust was analyzed to determine which isotopes of the elements strontium and neodymium it contained. Different soil sources will have unique "fingerprints" of varying levels of those isotopes, allowing reserahcers to determine just where the dust came from.

At lower elevations, the Central Valley contributed as much as four fifths of the dust collected. But the percentage of dust from the Gobi rose at higher elevation sites, reaching as high as 45 percent.

A hundred fifty years ago, the amount of dust coming off the Central Valley was likely far lower: much of the Valley was vegetated, some of it heavily, reducing dust flow into the atmosphere. Wetland forests that crisscrossed the Valley would have trapped much of the dust blowing off the semiarid western hills. A century and a half of plowing has greatly increased the dust blowing off Valley soils.

Overgrazing and desiccation have increased the amount of dust blowing off the Gobi in recent decades as well, but paleontological records indicate that Gobi dust has been reaching the West Coast for more than a million years.

Researchers found that deposited dust accounted for far more available phosphorus than breakdown of the Sierra bedrock, especially along streams where washed-off dust would accumulate in bends and shallows. That means it's likely that the Gobi Desert has played a major role in providing Sierra Nevada plants with the phosphorus they need for hundreds of thousand of years.

“In recent years it has been a bit of mystery how all these big trees have been sustained in this ecosystem without a lot of phosphorus in the bedrock,” said UC Riverside's Emma Aronson, lead author of the study. “This work begins to unravel that mystery and show that dust may be shaping this iconic California ecosystem.”

Aronson and her colleagues point out that as global climate changes, more and more dust will likely be blown into the upper atmosphere, likely playing a greater and greater role in mountain forest ecosystems.

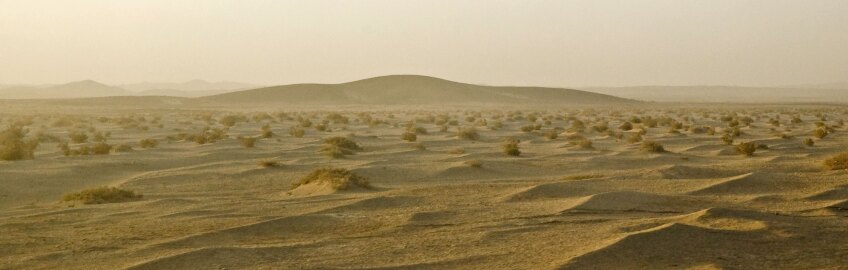

Banner: The Gobi Desert. Photo: chemophilic, some rights reserved