He Made Waves on the River: Lewis MacAdams Passes Away

Without Lewis MacAdams, an avowed poet, Los Angeles might have completely forgotten the river that birthed the city. “There would not be a movement to save or restore the L.A. river without him,” said Joe Edmiston, executive director of the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy. “He was able to provide some romance, some poetry, some vision that you didn’t see.”

Through his eyes and with his imagination, Angelenos re-awakened to their latent memories of the historic river Spain's Gaspar de Portola "discovered" during his explorations in 1769. Inspired, they are now creating for themselves a vision of a waterway that would carry Los Angeles into a lusher, more naturally connected 21st century.

“Nobody rises to Lewis’ level of gravitas. It mixes the visionary with irreverence for authority, but in a way that’s also politically skillful, so that he was able to get things done and change people’s minds,” said Sean Woods, former superintendent of California State Parks, Los Angeles Sector, and now chief of planning for the Los Angeles County Department of Parks and Recreation.

After more than three decades of work on the Los Angeles River, MacAdams leaves behind a legion of Los Angeles River advocates, significant victories on Los Angeles River-related projects, but most of all, a legacy of the power of art to drive politics. MacAdams passed away from complications from Parkinson’s disease April 21 at the age of 75. He is survived by his brother Alan, his sister Kathy; his sons Ocean, Will and Torii; his daughter Natalia; and his companion, Sissy Boyd.

Born in San Angelo, Texas, in 1944, MacAdams always straddled the world of politics and poetry. His parents were both politically inclined, and his time in New York "included advocating for civil rights as well as sleeping on people's couches, following poets around."

It wasn’t until he came to California, to a little town called Bolinas, however, that he found his calling. Bolinas Lagoon is a 1,100-acre tidal estuary that is home to diverse wildlife such as snowy egrets, warblers, seal pups and shrimp. When two oil tankers collided and caused an oil spill beneath the Golden Gate Bridge, MacAdams saw firsthand how the “whole town of a couple thousand people organized to keep this bunker oil out of the lagoon. And I saw in the three or four days that the community organized to successfully keep this oil mostly out of the lagoon that ... One, all politics is local. Two, that water politics is the foundation of all politics.” After his career in Northern California where he was a successful activist, he made his way to Southern California and was “captured by the river,” according to Edmiston.

MacAdams first saw the river while working as an editor for a short-lived but influential magazine, WET, which had the tagline “The magazine for gourmet bathing.” Young and broke, he would take the bus from the Downtown Arts District where he lived, to the magazine’s offices in Venice. The bus stop where he got on incidentally offered a view of the Los Angeles River. “I had never seen or heard anything really about the L.A. River,” said MacAdams in a 2013 interview, “but it was one of those strange moments when I knew that I would be involved with the Los Angeles River for the rest of my life. It brought together the major strains in my life: poetry and politics. I began to see that there was a way to combine together things that never before seemed to work together in my life.”

MacAdams seemed at first to be a strange cosmic choice to revive the ailing Los Angeles River in the 1980s, but it is precisely through his unconventional means that he was able to change people’s minds and perceptions. “He always had this goofy hat and walked around not really caring how he looked or what people thought,” recalled Edmiston. “A lot of us are projecting ourselves to the rest of the world. He didn’t need that. He was self-reflective.”

When he first began, MacAdams recalled, “everybody just laughed at me.” In 1985, he began his now famous 40-year art project with a one-man show at the Wallenboyd Theatre called “Friends of the Los Angeles River.” In it, he painted himself green, wore a white suit and became William Mulholland. By the second act, he would become by turns an owl, hawk, rattlesnake and frog — all river animals. His artistic gesture was a flop of epic proportions panned by the Los Angeles Times with the words, “with friends like MacAdams, the river needs no enemies.”

It turned out MacAdams was perhaps the best friend a river like Los Angeles' could have. By 1986, fortified by coffee and accompanied by friends Roger Wong and Pat Patterson, the three cut through the wire fencing on the Los Angeles River and declared it symbolically, artistically open. At the confluence of Arroyo Seco and the Los Angeles River, MacAdams asked if they could speak for the river and, having heard no negative response, thus began the organization Friends of the Los Angeles River (FoLAR).

In those early days, FoLAR was indeed more an art project than an official organization, but perhaps therein lay its power. By prioritizing artistic possibility over political realities, MacAdams' unconventional methods gave others tacit permission to imagine as well. “I learned from Lewis that you don’t have to have all the answers. You can have this vision and goal, remove all the procedural confusion and just have an end result. And work backwards from there,” said Shelly Backlar, a longtime colleague at FoLAR and now vice president of programs at the organization.

By 1989, FoLAR had organized its inaugural Los Angeles River cleanup, attracting all of ten people. Since then, it has become an annual, signature affair for the organization and brings thousands to the riverbanks yearly. "The Los Angeles River runs through the heart of L.A., and these earth-bottom sections of the River are a vital green space we share. Every year, the CleanUp connects people from across the county by bringing them to the River which ties us together," said MacAdams in 2015.

By 1997, MacAdams became part of Los Angeles mythology by throwing himself in front of bulldozers meant to dredge the riverbed in Glendale Narrows, which would harm the wildlife that called the river home. This wasn’t his most legendary act, however. It was what came after.

MacAdams’ bold move led him to a meeting with Los Angeles County Department of Public Works where a fierce argument ensued over semantics. “He loooooved a good fight,” recalled Backlar. By design, and perhaps as a way to mentally distance people from the river, government documents and maps all called the Los Angeles River a “flood control channel.” Every time officials used the term “flood control channel” at that meeting, MacAdams would continually interject with the word “river.” By standing his ground at a meeting with the Los Angeles County Department of Public Works, he would chip away at the impersonal overtones the label “flood control channel” has imposed on the Los Angeles River.

FoLAR would continue this long-term effort to change the minds of people in all its projects. The next year for example, on February 28, 1998, FoLAR, the Sierra Club and the Urban Resources Partnership organized the River Through Downtown conference at the Central Library. “It was the first big attempt to view the role of the river historically and to see what it could be, should be, because of its natural functions,” said Melanie Winter, who was then the executive director of FoLAR and now the director of The River Project. By setting up the conference, Golding, Winter and MacAdams challenged attendees to see the river differently, not just as a concrete channel and possible freeway.

MacAdams was an artist with a political temperament. Though he excelled in finding ways to open people’s worldviews he also understood that he could not accomplish everything on his own. “Keeping the place going had to be done, but it was not his focus,” Backlar said. “His focus was elevating something that people thought was ridiculous and was a joke.” Instead, MacAdams found the people and allies that would help his advocacy for the river.

It was his gift to be able to see what is possible not just in the river, but in others. At the time that Backlar interviewed for her first position as managing director at FoLAR, she readily admits to being eager, naïve and overly optimistic but “Lewis saw something in me. The reality is that I wasn’t the perfect person for that job, but I was the person that could work directly with Lewis. I didn’t have much guidance, but I had him,” she said. Backlar continues to bring people to the river to this day through education, outreach and its mobile classroom, the River Rover, at FoLAR.

Success followed this visionary’s strange ways. Achievements weren't accomplished alone, but by building the groundswell for the river’s revitalization. In this way, MacAdams helped resurrect a long-dead river in the hearts and minds of Angelenos.

In 2000, MacAdams’ organization, FoLAR, was part of an alliance that would sue to stop warehouses from being built on the Cornfield — and surprisingly, they won. Not only did the environmental groups succeed in stopping the planned development, their actions also allowed for the purchase, clean up and eventual public opening of what is now known as the Los Angeles State Historic Park in 2017. Thanks to another lawsuit filed by FoLAR along with The River Project and other environmental and social justice organizations, California State Parks was also able to purchase the Rio de los Angeles State Park.

With MacAdams at the helm, FoLAR would be an important voice in all things Los Angeles River. Former City Council member and now Executive Director for River LA, Ed Reyes remembers seeing much of MacAdams while at the helm of the Ad Hoc Los Angeles River Committee he oversaw for over a decade. "There was an initial tension between us because of the role he played in questioning authority, but when he raised issues and saw that we were also addressing them, we learned how to work together," recalled Reyes. "We had this constant dialog formally and informally. Sometimes he was amicable; sometimes very emotional and aggressive, but that was just his way of being and I was fine with it."

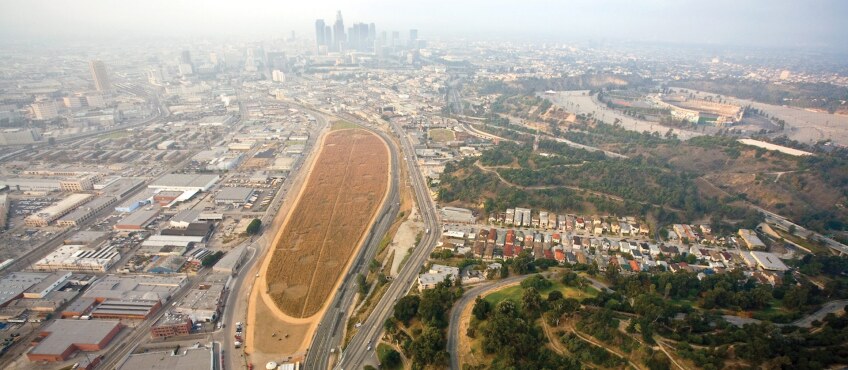

With a collection of groups working pro bono including Perkins and Will, Studio-MLA and Michael Maltzan Architecture, FoLAR also helped bring together a diverse group of people to work on a masterplan and vision for Piggyback Yard, the largest river-adjacent open space where restoration is possible. The site is now potentially included for development in time for the 2028 Olympics in Los Angeles. “He asked for a rendering,” said Leigh Christy, principal at Perkins and Will. “We ended up working together for about a year, leading the Piggyback Yard Vision and Master Plan — an effort that provided plenty of renderings, but also the researched substance to back up advocacy, further studies and funding. His focus on the vision, commitment to keeping it alive, and ability to navigate bureaucracies by inspiring the people within them — all were absolutely critical to the slow but steady revitalization changes now beginning to appear along the River.”

Piggyback Yard was in some sense a test run for how collaboration could look like along the Los Angeles River. “At that time, really robust conversations around active transportation and bike networks wasn’t pervasive,” Christy said. In this case, the Los Angeles River brought them together and continues to do so. “The River is a connector and not a divider,” according to Christy. This cross-functional collaboration would not have begun without MacAdams’ instigation.

Its role as an organization, which shows in its programs today, is to bring people to the river and allow the waterway to speak to its denizens. “[Lewis] always saw in the river this level of art and community and experience,” Backlar said, “He always referenced the song ‘Shall We Gather at the River.’” FoLAR’s current programs include facilitating river tours, encouraging community science along the river and bringing the river to schoolchildren via a mobile classroom. Because of MacAdams’ and FoLAR’s tireless advocacy, Los Angeles now has plans to restore river-adjacent areas and develop them with sound watershed principles in mind.

“He really has transformed the city and in the sense the world too by virtue of making ecology vital and not just a byproduct of the larger cultural conversation of design and civic infrastructure” said Julia Ingalls, author of a forthcoming book on the Los Angeles River revitalization.

MacAdams’ artful ways would inspire those who would come after him on the river, including Woods at California State Parks, who along with Julia Meltzer at Clockshop, would begin the Bowtie Project on the 18-acre post-industrial lot along the Los Angeles River, slated to be a developed as an open space one day.

“It would take an imagination of an artist to realize the full potential of a maligned and degraded flood control channel, and to see it restored into something of great value to the city,” Woods said. “[Lewis] was my inspiration in moving forward.”

Since 2014, the Bowtie Project has brought over 90 artist projects, performances and events, from campouts and audio tours by Rosten Woo to adobe structure building by contemporary artist Rafa Esparza.

“We had no funding for anything at [the Bowtie Parcel]. We had no funding for design, for remediation, but [Julia and I] thought this could be a great place to allow artists to come into the site, bring people out and have people start to imagine,” Woods said. Buoyed by the arts programs at Bowtie Parcel, California State Parks was able to raise $500,000 for a Bowtie Parcel conceptual design.

“Because of Lewis’ work, we’ve come to realize that art and arts programming is such a powerful tool in engaging urban communities,” Woods said. “That is probably Lewis’ greatest impact, changing the perception of the river, getting people to realize what a tremendous resource this is and how it connects so many of us in Los Angeles.”

In 2016, MacAdams stepped down from his role and turned over the reins to current Marissa Christiansen, president and CEO of FoLAR. “At the end of his days, I hope Lewis was cognizant of the impact he’s had on this world and on each of us,” said Christiansen in a statement. “He led such a winding, fabled, and momentous life — the kind that will live on in the memories of all he knew. May we all be so lucky to leave such a lasting and positive mark on the world.”

Top Image: Los Angeles River | U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service