Field of Dreams: The Cornfield Throughout Los Angeles History

It was Wednesday, August 2, 1769. Father Juan Crespi, a Franciscan priest, set out westward alongside a European expedition through California. On that day he spied “very large, very green bottomlands, seeming from afar to be Cornfield...”

Father Crespi’s description may just be a quirk of translation from Spanish to English, but water quality advocate, architect and former University of Southern California professor Arthur Golding likes to think that the explorer-missionary was marveling at a lush piece of land Angelenos now actually do call the Cornfield.

“This site is historic, beyond what is generally mentioned,” says Golding.

He would know. Almost twenty years ago, he was among the leading figures in a struggle to reclaim one of the last pieces of open land for the people of Los Angeles — what Angelenos would someday call Los Angeles State Historic Park (LASHP), a 34-acre park that opens this April 22, 2017 at 10 a.m.

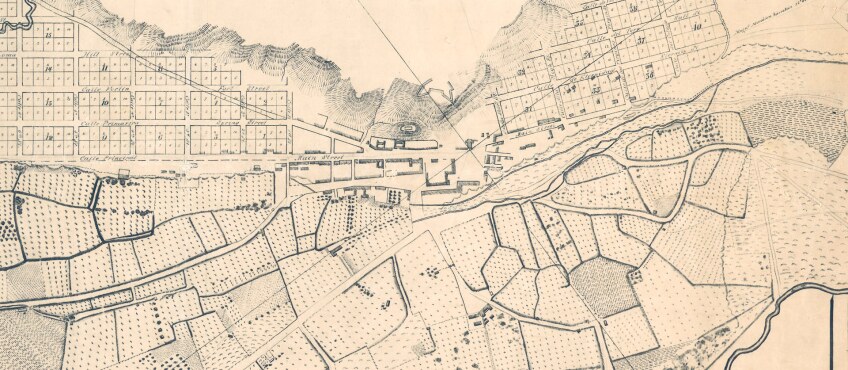

“The site was part of the floodplain of the Los Angeles River. It’s present even in the Ord map, the first map of the city of Los Angeles in 1849. If you look, you’ll even see the Zanja Madre [the original aqueduct that brought water to the city of Los Angeles from the LA River] running through the parcel,” continues Golding.

Since then — again and again — the Cornfield has woven itself through Los Angeles history, its fate intertwined with the city that surrounds it. Its transformations are a reminder of how far Los Angeles has come from being that humble pueblo Father Crespi first observed.

Placing the Cornfield in History

There is no clear reason why the land became known as the Cornfield. Some say it’s because of the corn seeds that used to tumble out of the rail cars and eventually grew around the land. Others say the wind carried corn seeds from the mill just south of the site. Or it could be because corn used to be the food of choice for the rail-riding hobos that grew their food on the nearby hillside.

What we do know is that in the 1800s, the land was part of a farming operation that grew corn and grapes, irrigated by the Los Angeles River. It lay between what is now Chinatown to the west and the Los Angeles River to the east.

Toward the latter part of the 19th century, it became a Southern Pacific Railroad freight depot and switching yard. Eventually the freight rail operations moved to the Inland Empire, leaving the old downtown rail yards empty and unused. Union Pacific bought the rail yards in 1991 and took over Southern Pacific in 1997. It was one of the last vast open spaces in the heart of Los Angeles that could still be developed.

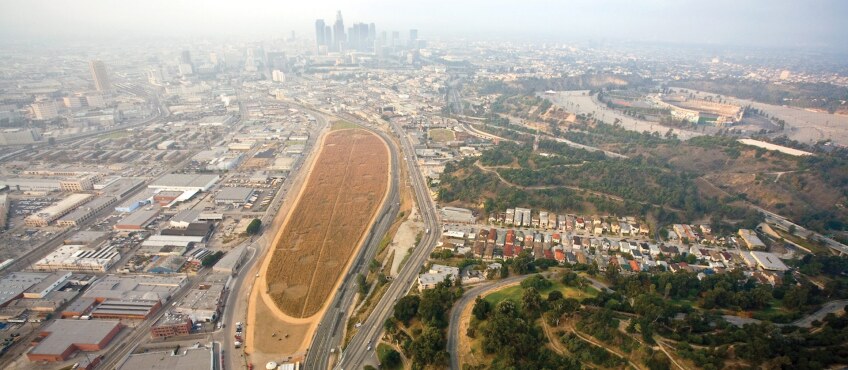

Its size and location made it priceless. The Cornfield is about the size of 25 football fields. It sits just a half mile north of Union Station, a transit hub that is even now making preparations to accommodate the California High Speed Rail. Four neighborhoods surround the site. On the north is Lincoln Heights. To the south is Chinatown. On the west is Solano Canyon. To the east is Dogtown, where Los Angeles’ oldest public housing development, William Mead Homes, is built on a former oil refinery.

There are at least 70,000 residents within these working class immigrant neighborhoods. As Sophia Cheng notes in her 2013 thesis, “Education and income in all neighborhoods is well below the citywide and county average. 28.3 percent of Chinatown and Solano Canyon residents, and 32 percent of Lincoln Heights residents live below the federal poverty line. 100 percent of the residents in the 450-unit William Mead Homes live below the federal poverty line.”

On this land, Majestic Realty Company, one of the country’s largest real estate developers, saw a chance to make a deal. Majestic already had the strong support of Mayor Richard Riordan and Councilmember Mike Hernandez. The company even had a $12 million pledge of financial support from the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), a key piece of funding.

The plan was to build the River Station Business Park, an $80-million “gigantic field of warehouses,” says Lewis MacAdams, founder of Friends of the Los Angeles River (FoLAR). The four buildings would total 909,200 square feet, half warehouses and the rest light manufacturing. Majestic promised to create 1,000 new jobs. Best of all, the proposal didn’t even have to change the site’s current industrial zoning, a process that could introduce delays. All the pieces seemed to align for Majestic Realty's owner Ed Roski Jr. “He basically had a done deal on his hands,” said Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) Senior Attorney Joel Reynolds.

What they didn’t count on was the growing sentiment that Los Angeles could do better.

The 1990s: Grassroots Planning and the Cornfield

In the '90s, James Rojas was just beginning his life in Los Angeles. He was renting a loft in Los Angeles at a now unbelievable price of $600 per month. “The city was changing,” says Rojas.

“It was an incredibly fertile time back then,” says Melanie Winter, director of The River Project. Now-luminary figures in environment and justice such as Dorothy Green, founder of Heal the Bay and an influential water quality activist, and Juanita Tate, a green justice activist, were already gaining momentum.

It was also an incredibly tumultuous time, when the Rodney King Riots of 1992 were fresh in the city’s memory. Suddenly, questions of justice, race, and environment were all intertwined amid the Los Angeles cityscape.

It was in this atmosphere that FoLAR, the Sierra Club, and the Urban Resources Partnership held the seminal River Through Downtown conference at the Central Library on February 28, 1998. “It was the first big attempt to view the role of the river historically and to see what it could be, should be, because of its natural functions,” says Winter, who was then the Executive Director of FoLAR. By setting up the conference, Golding, Winter, and MacAdams challenged attendees to see the river differently, not just as a concrete channel and possible freeway.

The conference, shaped by neighborhood focus groups held in January and February, was attended by the public and city and county legislators.

Winter says “We were able to bring together a lot of really good minds… to take a look at the possibilities near the river.” Architects, designers, community members, and river advocates in attendance were then able to plan not from a void, but armed with detailed background information. They got to hear what the community dreamed of for these sites, and plan with that reality in mind.

In the Cornfield they saw the “downtown Central Park for Los Angeles.” Instead of an abandoned railyard, they envisioned a new urban neighborhood that would link Chinatown to the Los Angeles River. Residences, offices, and shops would overlook a large park. Picnic areas peppered with trees, soccer fields, baseball diamonds, and a new middle school would inject life back into the new neighborhood called River Park. On one edge of the park, a new Zanja Madre would flow in parallel to a bikeway that would connect to Union Station, while a then-planned Blue Line to Pasadena would connect the community even further. “We knew that to make anything good happen, we had to make a compelling visual argument,” says Winter. They succeeded. The proposal was a win-win for the community, businesses, and the environment.

The results presented at the conference galvanized the community and bonds across different groups were newly strengthened by the conference. So when Majestic unveiled its plans to purchase the Cornfield in early 1998 without much community outreach, angered activists and surprised community members were quick to take action.

Getting Organized

Golding, MacAdams, and Chi Mui (a Chinatown activist, a senior field deputy for state Senator Richard Polanco, and later San Gabriel Valley’s first mayor of Asian American descent) were called the Three Amigos of Cornfield, recalls Golding. They were the triumvirate that founded the Chinatown Yards Alliance, a coalition composed of over 30 community and environmental organizations, ranging from the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) to the Chinese Benevolent Association.

While FoLAR's Melanie Winter was organizing the opposition to Majestic's proposal, she was also working with Dorothy Green on a park bond effort that passed in June 2000. Winter was tasked to develop a list of priority River projects, create cost estimates, and then seek the support of state legislators. Winter and Green’s efforts helped turn an initial $1 million estimate into an $83.5 million bond allocation. (The idea of setting aside a portion of the bond for Los Angeles River projects was first proposed at the River Through Downtown conference.)

Winter and Green's role in making funds available would prove crucial as the struggle with Majestic came to a head.

“There were many roads open to us and we took every single one of them that we could think of,” says MacAdams.

One of the Chinatown Yards Alliance's most valuable assets was Chi Mui’s connections. “We never could have made it without Chi. We just didn’t know the language, and the people,” says MacAdams. Castelar Elementary School came on board because the principal had become Mui’s friend, for example.

The Alliance had no resources and no money. While Mui was rounding up support, especially in the Asian communities surrounding Cornfield, other activists sought support from neighbors and businesses, spreading the ideas developed at the River Through Downtown conference.

“We were just slowly building this thing. There was no magic to it, just stick-with-it-ness. Eventually, people weren’t so afraid of what we were doing,” says MacAdams.

The ad hoc steering committee met frequently over dim sum at Gourmet Carousel to strategize. Community meetings were held all around the Cornfield. Those meetings shaped the evolving plan for the Cornfield, which Golding and several teams of designers incorporated into successive renderings.

“We talked to a lot of people with a lot of different interests. We may have ended with too many facilities in the plan,” says Golding. At different points, the community proposal included a public school, a Shaolin institute, a museum to commemorate the Zanja Madre, a farmer’s market, soccer fields, and a three-story structure with an open-air traditional Chinese roof on top.

“Everybody had their own idea,” says MacAdams, but they also “gave each other the benefit of the doubt.” The community simply knew they didn’t want any more warehouses, and a public declaration issued by the Chinatown Yards Alliance during the early days of the opposition called this a “once-in-a-century opportunity…to support a plan to build a middle and high school, sports fields, a park, and a bikeway in a community where there are none, and much-needed housing.”

The Alliance’s vision made financial sense, thanks in part to the funding Winter helped marshal. As Reynolds recounted in a 2000 op-ed for the Los Angeles Times, voters had previously approved Propositions 12 and 13, park and water bonds that could be used to help purchase the Cornfield. Governor Gray Davis’ budget already included money for L.A. River restoration. State and federal funds paid for the cleanup of contamination from the Cornfield's railway era, which turned out to be minimal. Stan Finney, a geology professor from California State University Long Beach performed testing on the site and said in an oral interview, “We were surprised at how little contamination we found in the property… It was only limited to three different contaminants: arsenic, lead, and total petroleum hydrocarbons.”

With community support, and the possibility of raising enough money to purchase the land, the question became how to persuade local leaders and developers to see their point of view.

The answer, as it turned out, was the law. The Alliance mounted a multi-pronged legal effort.

The Legal Battle

“It was a campaign to create a willing seller,” said attorney Doug Carstens, managing partner of the public interest law firm Chatten-Brown & Carstens. Back then, Carstens was fresh out of graduate school and had just joined Jan Chatten-Brown at the practice she had opened in 1995.

The first prong was to the challenge the developer’s plans on environmental grounds. In July 2000, a city planning commission approved the River Station Business Park without conducting a full Environmental Impact Report (EIR) under the California Environmental Quality Act. The Alliance demanded a full EIR that considered the park as an alternative. On July 25, 2000, the newly formed Central Area Planning Commission voted to deny the Alliance’s appeal. The Alliance once again appealed to the City Council, which again voted against an EIR, though it did carve out eight acres of the development as a community park.

Eventually, the Alliance filed a lawsuit to demand an EIR.

The second prong was a civil rights complaint. Robert Garcia of the Center for Law in the Public Interest (which has since become The City Project) had organized a civil rights challenge under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, which prohibits racial or ethnic discrimination in federally funded programs. He filed his complaint with HUD, which was providing loan guarantees to Majestic and helping pay for environmental cleanup.

Garcia argued that the fight for the Cornfield was part of the historic struggle for low-income people of color in Los Angeles to find livable communities with parks, playgrounds, schools, and recreation. Garcia cited the eviction of Latinos from Chavez Ravine to build Dodger Stadium and the relocation of Chinese families to make way for Union Station as examples of communities of color dislocated in the name of larger development goals. The Cornfield was not only a matter of environmental importance, but a matter of social justice.

Finally, there was the third, most personal prong. Much of Majestic’s business plan depended on that support from HUD.

The Alliance appealed to Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a senior attorney for NRDC in New York, a close friend of Reynolds. Andrew Cuomo, current Governor of New York who at the time was HUD Secretary, was then married to Kerry Kennedy, RFK, Jr.'s sister. “We put together a brief memo for him, and I said, ‘Bobby, take a look, talk to your brother-in-law. He doesn’t realize that this money is facilitating a project that will meet with tremendous opposition for the community. It’s not a project the community wants.’”

In an email conversation with Paul Stanton Kibel, professor of Law at Golden State University, Reynolds says that without the personal connection, it would have been highly unlikely for HUD, which is headquartered in Washington D.C., to intervene in a matter that would normally been left to HUD’s Los Angeles office.

Cuomo responded with alacrity, appointing a team to visit the Cornfield to assess the situation. Then, in a September 2000 Los Angeles visit, he announced that the $12 million package would not be released for the River Station without a full EIR. Cuomo's announcement meant a delay of a year or more, and put federal aid into question.

“When this happened, it changed the dynamic,” said Reynolds, “We began to talk about the possibility of selling the land to the state of California.” Majestic’s “done deal” seemed undone after all.

The Alliance’s quest to save the Cornfield also came during election season. Most of the candidates for mayor and city council seats expressed public support for turning the parcel into a park. One of these candidates was Ed Reyes, who was then working for Councilman Mike Hernandez. Reyes had come out in support of Cornfield Park because he “saw it as an opportunity to finally have a seat at the table, to use the planning police powers to raise the question, ‘What is the highest and best use for this land?’” Reyes eventually won the city council seat and went on to champion the Los Angeles River and other projects.

Three days before the lawsuit was to be heard by a judge, the Alliance and Majestic settled in April 2001. The Trust for Public Land (TPL) was brought in to purchase the land in the state’s stead, and in turn sell it to the State of California after cleaning up the property. If TPL failed to do so within a year, then the Alliance would agree to drop the lawsuit and Majestic would be free again to pursue its purchase.

At a December 21, 2001 press conference, Governor Davis announced that funds from Proposition 12 would help California State Parks acquire the property for $36 million. Santa Monica Mountain Conservancy would purchase the remaining acres. The purchase price was eventually set at $35 million from Proposition 12 funds and another $5 million for cleanup.

After 2001: Designing the Future

With the land purchased, the discussion shifted to what to put on the land. During the fight with developers, it was only necessary to build opposition to development, but not to agree on what exactly to build. The process of getting down to the details became thorny indeed.

A Los Angeles Downtown News article from 2003 characterizes the process as a “long-tangled process [that] has once again sparked disagreement among stakeholders, who are divided over how to develop the site.”

Three alternatives were proposed. The first would turn the site into a largely open space used for recreational activities. The second involved rebuilding historic structures, including a hotel and a train roundhouse. The third would develop most of the space to provide community services.

Meanwhile the land was used for pick-up games, overnight camping, music festivals and art shows. The community waited.

The Cornfield might have faded from public awareness had Lauren Bon not turned the land into an art piece. With $3 million from the Annenberg Foundation, Bon, a director of the foundation, turned the site from a brownfield into an actual cornfield. Ears of Indian corn swayed under the sunlight in 2005.

“When she did that, it made believers out of many folks, who felt this would only benefit the elite and wealthiest of people,” said Reyes.

The project not only kept the Cornfeld in the public eye, it also helped clean the land. Geologist Finney says that “When you grow corn in one area, the roots from the corn takes it out of the soil, but the contaminants don’t go into the corn ears. It’s a miracle plant. It absorbs bad chemicals, but doesn’t do anything to the corn ear.”

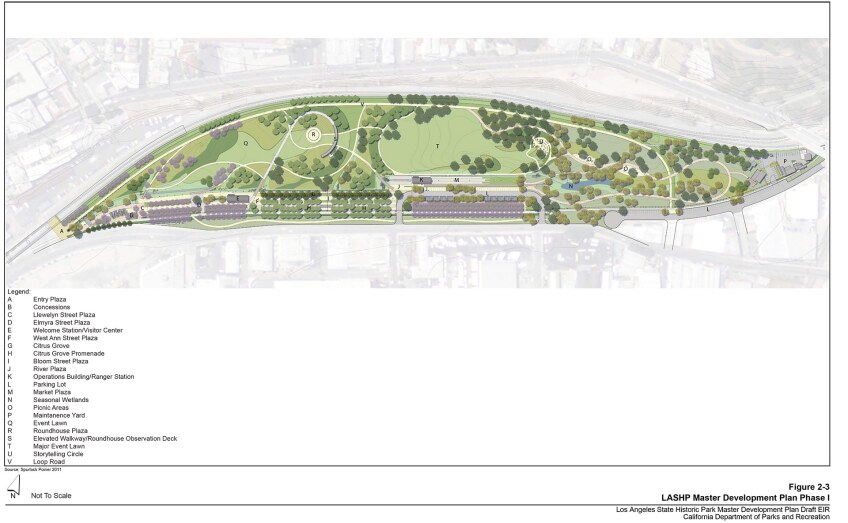

None of the three alternatives were realized because of the economic downturn. After the park came under the jurisdiction of the California State Parks, the design was in the hands of a 36-member Cornfields Advisory Committee. They eventually chose the proposal by San Francisco-based Hargreaves Associates, which combines a large public plaza, a lawn and a section of wetlands.

An in-house State Parks team eventually took over the design. This April, the public will be able to walk around an eye-shaped field, divided into three sections. At the southernmost tip, there will be a welcome pavilion, a children’s play area and a large meadow with walking trails and trees. A walkway will curve around the site of an old locomotive roundhouse, ascending to about 16 feet and providing views of the neighborhoods surrounding the park. A tree-lined promenade and a citrus grove might also play host to a farmer’s market. The park will have a two-acre wetland and river habitat area, which will include picnic spots.

MacAdams says that seeing the park finally open makes him “ecstatically happy, just because it’s a model for other communities organizing themselves.” He adds, “This thing has taken so long, it’s taken lifetimes. [The park] needs to be simple. Trees and grass. Grass and trees. Not gigantic video screens.”

Others are dissatisfied. Garcia lauds the victory — “This kicked off the green justice movement in Los Angeles,” he says — but laments the speed (or lack thereof) in development. “It’s been 17 years and that’s a long time in a life of a child without access to a park.”

Garcia adds that Cornfield Park is not the park he fought for because of the gentrification that has happened since 2001. “Since then, the people who lived in the neighborhood can’t afford to live and work nearby.”'

Winter also contends that the Alliance should not have settled and litigated instead, following the route Taylor Yards had taken, with the River Project in the lead. One of the provisions of the Cornfield settlement was that the value of the site would be based on the value of the land, had Los Angeles approved the River Station project. This upped the land value and consequently the purchase price for the brownfield. Winter worries that this increased purchase price has led to higher prices for other River-adjacent properties, hampering land acquisition for other Los Angeles River projects.

Nonetheless the legacy of the Cornfield remains. What is now a park, seemingly pristine and serene, has been at the crossroads of history for a long time now. On its canvas, the hopes and dreams of a community have been written and re-written. As it opens this month, one hopes that its historic legacy of diverse cooperation and engagement is something the city can continue to harness.

Top Image: Not A Cornfield