'Even the Animals are Asking for Help': A Conversation With Marine Biologist Phil Dustan

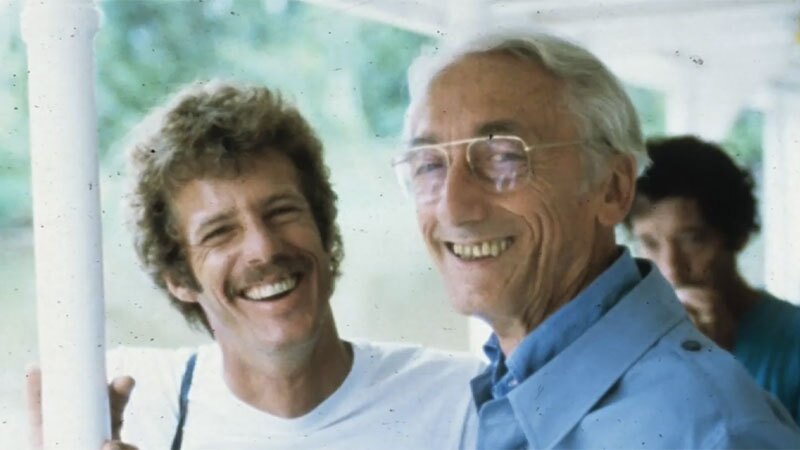

During the production of Earth Focus: Vanishing Coral, Philip Dustan, PhD, a marine biologist at College of Charleston, served as the film’s corals advisor. Phil has been studying coral reefs since 1969, and worked in his early years with undersea pioneer Jacques Cousteau.We spoke with Phil in April.

Chris Clarke: You worked with Jacques Cousteau on the Calypso. That’s an experience that those of us who grew up watching television in the 1960s and 1970s might envy very much. I wonder if you could say a little bit about how you happened into that connection, and what kind of influence it’s had on you.

Phil Dustan: Well I got asked to meet Captain Cousteau to talk to him about Caribbean coral reefs. They were making a documentary about reefs in the Caribbean, and they wanted somebody who knew the reefs.

I got a call one day. I was fresh out of graduate school, running a lab in Key Largo. I was coming back in [from the field]; one of the guys in the base station said “hey Phil, Captain Cousteau just called you. He wants to talk to you.” And I said “wow.”

It was actually somebody from the Cousteau Society. They wanted me to talk to Captain Cousteau about coral reefs, and to see if I could go with them on an expedition in the Caribbean. I met him in the Miami airport. We got along pretty well. That got me involved in two trips to the Caribbean: one to Belize and one to Jamaica, where we filmed a movie called Mysteries of the Hidden Reef.

About three or four years later, when I had just come to the College of Charleston, I got a call from Jacques Constans, who was the vice president of science for the Cousteau Society the French, sort of an industrial scientist. Really neat guy. The phone call went something like: “Phil, the Calypso is going to go to the Amazon. What equipment should we buy?” And I said “Well, what’s your question?” He said “Well, we are going to the Amazon. What equipment should we buy for science?”

And I said “Well, what’s your question? What are you trying to find out? If I know what the question is then I can help you with equipment.” And he said “Maybe you have one?” (Laughs) On the spot I said “You know JYC” — we used to call Cousteau “JYC” [pronounced “Zheek”], that’s his nickname — “he always talks about rivers as the roots of the ocean. So let’s look at how the Amazon contributes to the ocean. And we will essentially go all the way up the Amazon and look at chlorophyll concentration and the biological oceanography of the main river and the contribution of each little river to it. And that JYC said “Great! Join us.”

And so two and half months later I was the principal scientist on Calypso as she went up the Amazon River. (Laughs)

And you know, we all talk about how the Calypso is so glamorous, you want to stand on the bow and see the whales and the birds and the dolphins go by and the world is so great. And that happens about five minutes every day. The rest of the time you are down below working your butt off to get your science done. You’re hard core at work. That’s all business all the time.

CC: You started studying coral reefs in 1969. What kinds of changes have you seen since then?

PD: The people that start working on reefs today have no idea what those coral reefs looked like, especially in the Caribbean. In the Florida Keys we’ve lost over 90 percent of our live coral cover. Visit a reef today and it’s like going to a graveyard.

In Jamaica on the north coast, where we had the most magnificent reefs in the Caribbean — they were well known to science — we are probably down to 15-20 percent of what was there. Environmental devastation in all its different forms is having an impact on these systems. They are just coming apart structurally and biologically.

A large part of that is land-based sources of pollution, over-fishing, dynamite damage, and now we are seeing ocean acidification and the impacts of the thermal heating of the ocean.

CC: Aside from getting in the water yourself, is there any way to measure the damage on a global scale?

PD: Sure. Let me start from the beginning. The beginning of measuring coral reefs via remote monitoring started out of scientific curiosity, and the earliest studies are from the early 1970s. My data from Jamaica is like base line ground zero data; it’s the earliest point of the studies of reefs in Jamaica and the Florida Keys.

So we first started doing this underwater, with transects, and people would say “well, that’s just that reef that's changing. What about the reef over here? It’s fine.” So I began to try and see if we could use remote sensing to study reefs.

At one point in the Biosphere Foundation, Gaie Alling and myself and a whole coalition of people wanted to build and launch a satellite that was just dedicated to studying coral reefs and coral reef changes. Because we felt we could document the changes, and show the world what's happening. People would respond, and we could further coral conservation.

Today, it’s really possible to take the satellite imagery that’s available and collect it all around the world, and show reefs changing. It’s not rocket science anymore. But it takes money, and it takes political will. People really don’t want to know what’s really happening. That’s the real issue. You have to get the public to care and you have to get the politicians to care. The scientists care. The people who study the reefs care, the people that live on the reefs for a living have to care because they see their lives disappearing in the sea.

But on the other hand you really have to want to [help the reefs]. That would mean that we would have to have some game plan to do it once we find out what’s going on.

And that’s what we don’t want to do. If somebody came to me and said what will it take to save the reefs? I’d say “what will it take save the biosphere? I don’t know: three, four, five times the effort of World War II for twenty years? We might start to make a dent in what’s happened. People don’t want to commit to this mobilization towards saving our home.

CC: What kind of specific measures do you see on that scale that would help? I assume reducing CO2 emissions would be part of it.

PD: Yeah; we would have to reduce CO2 emissions. We would have to go back to conservative nature of ecosystems. Most ecosystems retain nutrients within them. Forests are essentially storage for nutrients. And when we come along and we destroy the forests, or we destroy the prairies, the stuff just bleeds into the ocean. So we have to go back to helping nature reconstruct the planet to get a functioning biosphere again.

I tell my students, “imagine you have an animal, and it’s a functioning organism, and then you sort of cut its belly open and it just bleeds out. That’s what we are doing to the Earth.” We are taking ecosystems and, one by one, just going in and chopping them up, and they are just bleeding out.

And we need to get off carbon. We would use solar energy and wind and other forms of natural energy and we would have a far healthier life.

CC: It’s interesting to think that things like sustainable forestry and soil conservation in agriculture are actually things that could directly help coral reefs to survive.

PD: Oh yeah. Reefs are like the canary in a coal mine. They are indicators of the quality of life in the ocean. They are probably the highest expression of life in the sea that we’ve discovered. They’re more different kinds of animals, and plants, and bacteria, and viruses and anything else you want to go look for on a vibrant coral reef then any place else.

So it’s the most sensitive indicator of the way the Earth is changing. And we haven’t been watching it, because it’s underwater. We didn’t even know reefs existed until Captain Cousteau made his films and brought them onto our television screens. We saw them in our living rooms and went “wow, look at those things!” Most people didn’t know that they existed, and now scuba diving is multi-billion dollar a year industry.

It’s kind of interesting that scuba divers go to see reefs, go to take pictures of reefs, they come home to tell stories about reefs, but the industry itself doesn’t really contribute to their conservation, except in a minimal way. It’s individual people that install the mooring buoys [to reduce anchor damage to reefs].

For the most part, the scuba diving industry is just selling equipment. They’re now involved in “free diving,” which is sort of become a new avant garde sport. They’re now selling spear guns again. “Let’s go out and spear more fish?” That’s ecologically irresponsible. So the people that use the resource aren’t even doing much to help save it. They just live off of it.

And I think a large part of that is because it is underwater. So you go down, you see it, you come back, everything's fine, you watch the sunset, you have a margarita.

CC: Is there anything that you see happening that makes you hopeful for coral reefs?

PD: I see more people interested in trying to tell the story the way it really is. I had a small part in Jeff Orlowski’s new film Chasing Coral. I met Jeff in the Florida Keys; I took him and Richard Vevers and I showed them the reef. They didn’t know what they were looking at, at first. I said “this was alive once, and now this is all dead." And it was like it clicked, and they put together a movie that is very powerful.

Vanishing Coral is that same sort of documentary. And so I see more interest from that point of view.

Phil Dustan encounters a moray eel on Dancing Lady Reef | Video: Liv Wheeler

Next we need somebody that wants to get involved from the standpoint of changing behavior. Sort of like how do we sell toilet paper? Or how we do we sell some skin softener or a fancy car: let's take that understanding and focus it into how do we save the planet. Because it’s not just reefs, it’s the planet.

CC: You’ve spent a lot of hours in among the reefs. When you think about all those hours, is there a particular experience that stands out in your memory?

PD: There’s one that almost gives me chills whenever I tell the story.

I left Discovery Bay in the 1970s. This was the reef that I’d grown up on, and had hundreds of dives on.

I went back in 2013. We went down and we dove into the reefs and we photographed them and we surveyed them. I was horrified by the changes I saw.

The very last dive, my dive partner and I decided that we would do a dive down in what we call the nose of Dancing Lady Reef. Now Dancing Lady Reef starts at the surface and goes down, and then there’s a drop off at about 180 feet. There’s sort of a ridge line that goes down to the drop off, and that’s what we call the nose. It was the most beautiful, calm day. The visibility was gorgeous, and when you get that deep it's blue. And it’s just really magical, and also you are aware of how dangerous it is.

At about 100 feet there’s an opening in the reef. And there was this huge green moray sitting there about a third of the way out of its hole looking at me saying “Hi, Phil, I'm glad you're back.”

In 1974 I had let a moray out of a fish trap on a mooring dock. That night on a night dive in that very same region of the reef I put my hand on a coral and pulled myself to look at something, and the moray was about six inches from my hand. And it wasn’t a particularly large moray but it was a healthy one.

And when I saw this moray this last dive, I could have sworn it was the same fish. And it just gave me chills. It was like “I had your back and you guys didn't help us! You need to do something.” And morays live over 80 years in captivity. It was about 40 years since I had visited that reef. So it could have been the same animal. I like to think of it as “there’s still some stuff left there that needs to be worked on. Come on, even the animals are saying ‘you need to help us.’”

Many thanks to intern Amanda Pinedo for transcribing this interview.