Elysian Valley Residents Prefer Low-Density and Affordable Housing, Says Report

Outreach is an integral part of any local project, but it's often been shoved to the backburner as an afterthought in the greater scheme of things -- perhaps because of lack of resources or time -- which then sometimes causes an uproar further down the line. Not so in the neighborhood of Elysian Valley, at least in this case.

Non-profit design organization LA Más has recently released its Futuro de Frogtown report, commissioned by Julia Meltzer of arts organization Clockshop and David Thorne of dining venue Elysian, outlining just what it is that Elysian Valley residents think, feel, and want to see, as their neighborhood changes in the face of looming redevelopment along the Los Angeles River.

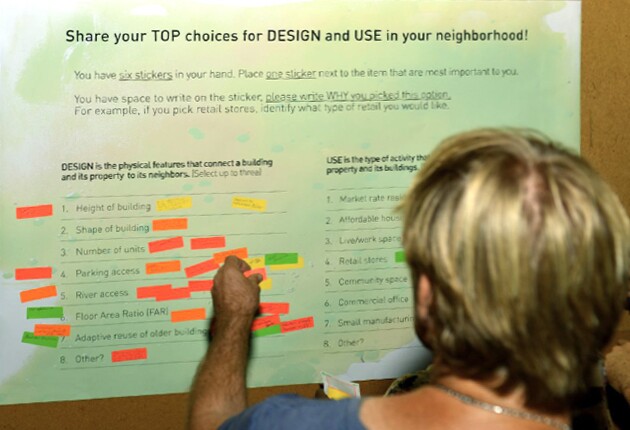

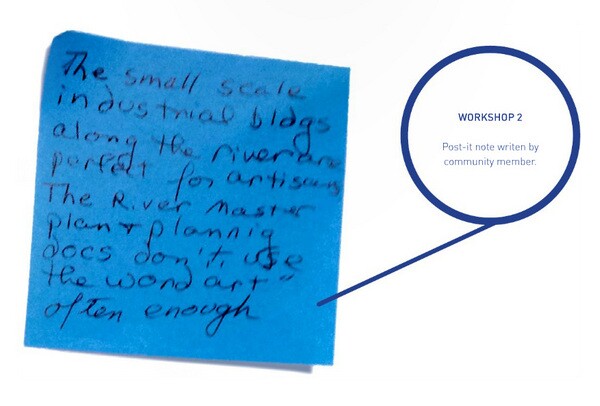

After five months, six weeks of interviews, and six community engagement workshops held in different venues, with ads and flyers in Spanish and English, the completed report found that the community was not receptive to high-density projects that would open up the quiet neighborhood to a larger population, especially considering its small streets and sparse mass transportation options. It would, however, consider adaptive re-use projects (development that would re-use the many industrial buildings in the community) and affordable housing projects. In addition, it wanted to see its homegrown businesses taken into consideration when looking into building the neighborhood economy.

The report found that addressing redevelopment by changing the neighborhood's Q Conditions -- additional regulations overlaid on a property, meant to ensure lower building heights or open space requirements -- is just the first step in a long, ongoing conversation about the community's future.

"In reality, Q conditions aren't enough to address all the issues the community has," says Helen Leung, LA Más' Director of Social Impact, and an involved member of the Elysian Valley community. "Let's broaden the conversation, take the conversation and provide different perspectives."

Leung grew up in the neighborhood, worked at then-Councilmember Garcetti's office, then was educated in The John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, and returned to work with the community through LA Más.

"Helen is someone from the community," says Elizabeth Timme, co-director of LA Más, "She's a broker between the working and creative class in the neighborhood." Though Timme and Leung both acknowledge that classifying residents as "working class" and "creative class" can be divisive, they do believe these labels can be helpful in highlighting the different views within the community. According to the report, Elysian Valley is a "predominantly Latino neighborhood that has been reshaped by the influx of creative neighbors, such as architectural firms, design shops, art studios, and restaurants."

The neighborhood's desires may seem like "pie in the sky" requests, balancing one benefit (affordability) versus another (low-density), but they were made by an informed neighborhood who understood exactly what they were requesting. This was LA Más's goal. Rather than asking the community what options they preferred to see in their neighborhood, the organization instead ingenuously created a hybrid education-outreach process, which resulted in informed neighbors making thoughtful requests. LA Más even hosted a workshop co-facilitated by Mott Smith, a developer and adjunct professor at the University of Southern California, who provided a real estate perspective.

"We partnered with the neighborhood watch, the neighborhood council. We put flyers in different places. We offered food and childcare. We tried to have meetings in different locations that were more welcoming. We put out dates early," says Leung. "We tried to appeal to the people who wouldn't normally resonate to neighborhood council format. As much as possible, we made the events fun and informative, which we think was successful. Once we got someone to show up, they'd bring a neighbor at the next one."

Though the community's requests seem difficult to achieve, the LA Más' report goes further by suggesting actual strategies that can be adopted by policy makers, developers, and the urban-minded to make these desires more plausible. Some of the organization's recommendations include: designating the primary use of buildings to commercial instead of residential, advocating preferential treatment for locals when it comes to rental or purchase options in the community, and requiring a community-wide infrastructure fund into which new development projects can pay.

Information such as this is a valuable guide for developers looking to build in the community, though it isn't meant to be an exhaustive checklist. Nevertheless, some of the report's suggestions can be seen in propositions such as the Elysian Valley Creative Campus, which aims to use local labor in its construction and offer discounted rates for non-profits, river, or community businesses.

Leung says about the proposed development, "Trying to look at just one development project is not as productive as thinking about the holistic development of the neighborhood." She says diplomatically that every development has different propositions within the community and have "different pros and cons." Discussing each specific project's merits and reducing the report to simply a laundry list defeats the report's greater purpose of facilitating true community understanding.

The recommendations are enlightening, and show creativity in finding new solutions based on community-focused needs. By the end of the 60-page report, readers are left with a better insight into the neighborhood, and perhaps a surer foot forward, when it comes to creating the future Elysian Valley. Leung says that is exactly what the report is supposed to achieve. It is geared toward those shaping policy, developers, and community organizations and leaders with an eye toward giving them insight into the neighborhood's rich history, assets, potential -- and what their role could be given what is already present.