Birds, Kids, and Climate: Could Taylor Yard Become a Park That Serves Them All?

Created in partnership with Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.

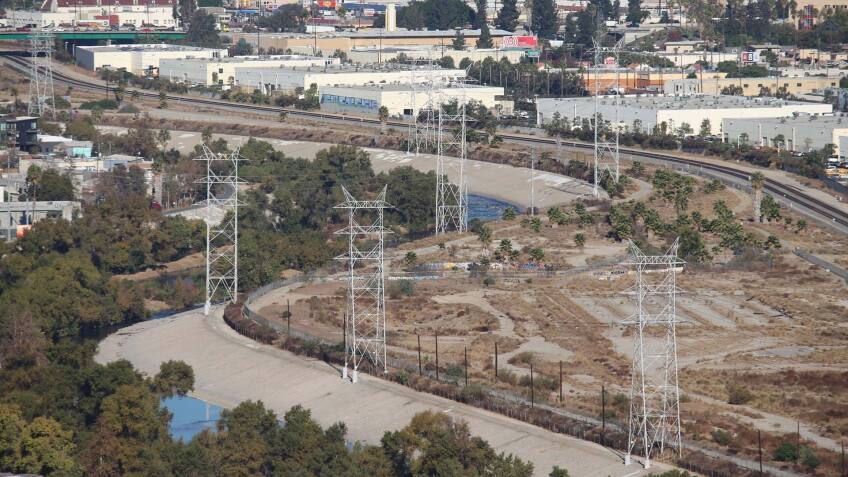

Two years ago, the city of Los Angeles purchased a portion of a former railyard for $60 million. This is the G2 parcel of Taylor Yard, one of the largest pieces of land on the L.A. river. The city plans to decontaminate the site and redevelop it as open space, which would be the most significant step so far in the increasingly real project to “restore” the river. This spring, the city released three conceptual designs for what this new park might look like.

Activists and planners have pushed for a park at Taylor Yard for decades, and their visions for the site don’t always align. Some see it as a potential new park in a park-poor neighborhood; some as a possible driver of Northeast L.A.’s ongoing gentrification; some as part of a 51-mile piece of water infrastructure, vital for managing Los Angeles floods and droughts in the face of climate change; and some as a place to rewild the river and bring nature back into a concrete metropolis. So it’s no surprise that the three designs set off a contentious debate about the future of Taylor Yard and the river. For its critics, the city’s plans didn’t follow through on Taylor Yard’s complex promise.

Now, the city has changed course. Rather than choose one of its three designs for G2, the city has announced that it will work with the State of California to plan for the whole, almost 100-acre Taylor Yard, including the adjacent Rio de Los Angeles State Park and Bowtie parcel, which will also become a park. The increased scale could give the city the space and the time to resolve the ecological and social conflicts that surround Taylor Yard, and to craft a unified vision for a grander site.

One of those conflicts concerns the famous concrete. Since the 1930s, the river has been paved for most of its length, to protect against floods. And since the 1980s, when activists introduced the idea of restoring the river, removing at least some of the concrete has been central to their vision. Concrete removal became an official priority when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineer and the city together endorsed a plan to restore habitat along 11 miles of the river, which specifically calls for widening the channel at Taylor Yard.

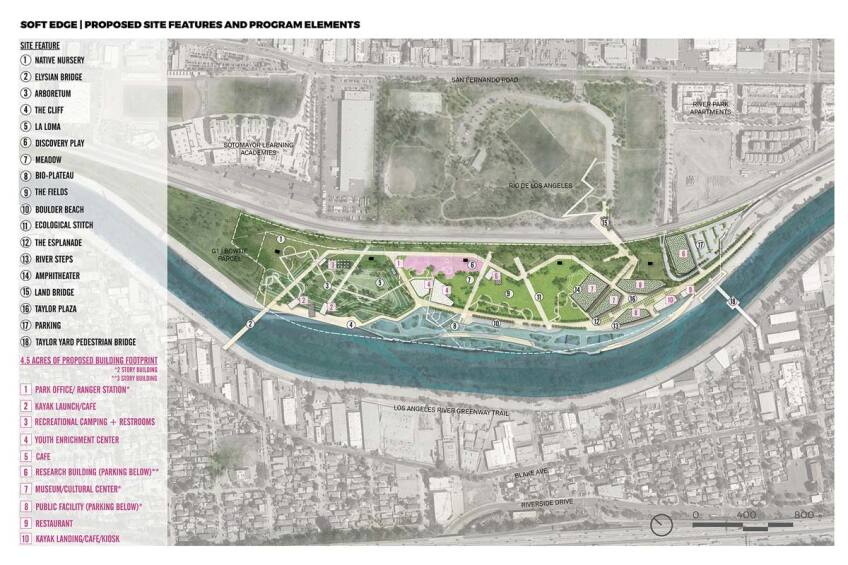

This plan for the river aligns with two of the city’s proposals for Taylor Yard, which imagine removing concrete from the site. One would involve cutting land away to create an island. The other, the “Soft Edge” concept, would widen the channel by creating a series of terraces that step down to the river. When stormwater fills the river these terraces would flood, creating wetland habitat and imitating, to some degree, the earlier ecology of the river, which regularly flooded the land surrounding it. Making an island would also serve to create new habitat, if it’s possible.

The city’s third design, however, calls into question how committed its planners are to this vision. Called “The Yards,” it would leave the concrete in place and the channel unchanged, essentially placing a new park above and beside the river. Unsurprisingly, some activists oppose what they see as a deviation from a necessary focus on park space and habitat. Friends of the L.A. River came out against “The Yards” idea with an op-ed for the L.A. Times and a “Crack the Concrete” campaign pushing the city to “liberate the river and reclaim our connection to nature” by removing concrete at G2 and elsewhere.

Others question whether a commitment to new parks and habitat requires removing concrete. Architect Frank Gehry, who has been working with Los Angeles County to update its river Master Plan, has said several times that he does not believe the concrete can be removed, and has apparently shifted his focus to building parks on platforms over the river. Instead of transforming the river itself, planners could look for opportunities to add parks and habitats around its margins.

City officials say that all three designs are intended to create the same quantity of new habitat; the Yards would do so by pumping river water into wetlands and gardens, and via areas focused on upland, rather than riverine, ecosystems. Still, they acknowledge that the Yards represents a different set of priorities. According to Michael Affeldt, director of the LARiverWorks team at the Mayor’s office, “The Yards is not a choice among equals.” Instead, “it’s a depiction of the realities of the constraints and opportunities of the site.”

The site’s constraints include the river channel and the floods it protects against — officials are clear that any plan for Taylor Yard must maintain or improve the channel’s capacity for flood control. Other challenges include the contaminated soil from G2’s railyard days that will need to be cleaned, removed, or covered; the active railway that still runs along the site’s eastern border; and a set of electric towers just next to the river channel that carry power to downtown L.A., which would need to be moved if any concrete is removed. So, The Yards is a kind of thought experiment that “takes those constraints and asks the ‘what if’ question: What if changing the river bank is not as feasible as we hoped it will be?” says Affeldt.

The city is eager to make something of Taylor Yard quickly. Deputy City Engineer Deborah Weintraub worried aloud at a recent public meeting that if the creation of the park is delayed, policymakers might change their minds. Some officials have said that their goal is to have the park ready by the 2028 Olympics, one of Mayor Eric Garcetti’s signature projects. If the city projects the cost of decontamination to be too high, or the risks created by a free-flowing river too great, or the time required to reshape the site too long, the Yards suggests ways to create park space and habitat — vital aspects of human health in a city that badly needs them — without fundamentally rethinking the river’s role as a flood channel only.

For some longtime river advocates, however, the whole point of restoration is to turn the river into something more; into a functional river. In other words, Taylor Yard could be something more than a park. Melanie Winter considers it “one of the most important sites in the city for climate adaptation.”

Winter is executive director and founder of The River Project, which advocates for what the group calls “watershed planning”: instead of single-used, concrete-based flood control, this approach looks for ways to reduce flooding and reclaim usable water, while creating habitat and recreation space, by building “with nature, rather than against it.” On this view, the river is a part of a huge hydrological and climatological system that must be transformed for the 21st century. And that means, in part, building public spaces that use soil and plants, rather than concrete, to absorb and filter water. Winter has spent decades arguing that Taylor Yard could be a model for this kind of planning.

Watershed planning is especially important there, says Winter, because the neighborhoods surrounding Taylor Yard face some of the most significant flood risk anywhere on the river. To address this, some planning documents have actually contemplated increasing the amount of concrete in the river, by lining the soft bottom of the Glendale Narrows near Taylor Yard — one of the few stretches of the river that supports plant and animal life and arguably the main reason river restoration is even a conversation today. Instead, Winter thinks Taylor Yard an opportunity to “reclaim the floodplain.”

That would mean widening the channel and letting water flow into the parcels where it would percolate into the soil and support plants. According to Winter, this could mitigate flood risk in the neighborhoods downstream of Taylor Yard, by slowing flow rates and retaining water. “It would also, if you restore floodplain habitat on that site, absorb carbon. Wetlands and floodplains are some of the hardest workers for carbon sequestration. You don’t need special technology — they sequester carbon like crazy.” Slowing the river could also contribute to a larger effort to capture and filter water to reuse even a fraction of the millions of gallons of water currently flushed out to sea every day, in a city that imports 85% of its water.

Christopher Hawthorne, the city’s chief design officer, told the L.A. Times that the city sees G2 as, among other things, “a water reclamation project in a time of climate change.” But Winter and River Project see the city’s plans so far as a sign that the “the future of Parcel G2 may be diverging” from a vision focused on natural spaces and systems: “the designs they put on the table did not incorporate any scientific information” to indicate how they would affect the river’s hydrology or habitat; whereas they do include 4.5 acres of planned buildings. (City officials say these are the result of surveys indicating the public wants places to eat and conversations with policymakers interested in including a cultural institution, like a museum.) Winter points out that building these structures would itself increase the project’s carbon budget, at a time when L.A. is positioning itself as a leader on urban climate adaptation. “When you can have ecosystems that reduce rather than create carbon, you want to take advantage of that as much as possible.”

Much of the debate around Taylor Yard has focused on its role in the city’s and the river’s ecology. But as the city moves forward, the project’s social dimensions will also become more visible. Irma Muñoz, director of the nonprofit group Mujeres de la Tierra, has spoken with local residents as part of the city’s public outreach for the project. She says people are excited about the prospect of a new park. She has found Local Angelenos are eager for a park that could provide “a connection with the river” and with nature. But the two things people bring up most in her conversations are flood control and gentrification.

Indeed, debates around river revitalization have shifted in recent years to encompass concerns about L.A.’s housing crisis, for instance, with critics holding up projects like New York’s High Line as exemplars of the “green gentrification” that can accompany such huge public investments. At Taylor Yard a fight is brewing over a proposed housing development, which some see a chance to address the city’s housing shortage, while others see a land grab on behalf of private interests.

Taylor Yard’s planners have had little to say about gentrification so far; unsurprisingly, designers and engineers have mostly treated the site as a design and engineering problem. But researchers and activists have created models to address park planning and housing justice together. For instance, a new partnership called LA ROSAH (the Los Angeles Regional Open Space and Affordable Housing collaborative) advocates for planning that addresses park and housing inequities jointly, and includes as a partner at least one public agency (the Mountains Recreation & Conservation Authority) that has a role at Taylor Yard. L.A. County’s in-progress update of its “L.A. River Master Plan” includes a detailed section about how river projects can fight displacement and protect the people living near the river now.

In addition to a housing shortage, L.A. is also deprived of park space as well. It’s important to remember that whatever else it becomes, Taylor Yard will also be a neighborhood park in an area whose low-income, mostly nonwhite residents have often been neglected by large-scale planning. These needs — for green space, for livable space, for a stable climate — are in complex tension, and it’s difficult for planning to address them all.

But perhaps it can, if everyone is at the table. When the city started planning for Taylor Yard, youth sports groups pushed for soccer fields at the new park in place of habitat. With the city’s help, a coalition of groups including the Anahuak Youth Soccer Association and the Los Angeles River State Park Partners (LARSPP) agreed instead to find funding for improved soccer fields at Rio de Los Angeles State Park next door, thus preserving space at the G2 parcel for natural space. In this case, the 100 acres of Taylor Yard provided room for multiple human and nonhuman needs. For Patricia Pérez, chair of the LARSPP board of directors, that’s a model for what can be accomplished if planners look at Taylor Yard as a whole and work closely with people in the communities around it. “Many cities have great parks; very few have world-renowned urban river restoration projects that turn a concrete channel into vibrant habitat for nature and people.” Fewer have made economic justice an explicit part of their park planning.

Places like Taylor Yard are good for thinking about the social and ecological consequences of living together at scale. Planning that addresses those consequences head on could be as much a model for other cities as the new river and the new park.