The Kawana Family Keeps the Surimi Tradition Alive

Chances are you've had a number of surimi-based products without even knowing it. California rolls, seafood salads -- and even Mexican ceviche tostadas -- all usually have it as an ingredient.

So what is surimi? Simply put, it's what fish cakes are made out of. It's a part of Japanese tradition that goes back over 1,000 years. Developed as a means of preservation, the process involves filleting white fish -- traditionally pollock -- then washing and squeezing out the moisture and oils from the meat, leaving with essentially a tasteless, blank slate of protein. This can be molded into any shape or form with any flavor, from its most traditional form, kamaboko, to the more recent products that can be found in many everyday American foods.

Otoichi Kawana opened the Yamasa Fish Cake Company in Los Angeles in 1938. At the time the Japanese-American population in Southern California had grown large enough to support eight other kamaboko manufacturers in the area. Today Yamasa is one of only two left in the United States mainland.

"Kamaboko business unfortunately is a dying industry," says Frank Kawana, Otoichi's son and now-retired president of Yamasa Enterprises. "Young people, they are exposed to hamburgers, pizza pies and all this, and kamaboko is not that tasty in that sense."

It's a sentiment echoed by Teiji Kawana, Frank's oldest son and current head of the family business. "Immigrants, after second or third generation, they don't tend to eat traditional foods," he says.

Thirty years ago kamaboko was sold exclusively to the Japanese. Today, the percentage of sales to the Japanese Americans has declined, but now it's made up by the popularity within the Korean and Taiwanese population. But even that may not last for long, as Teiji believes that "as they become second and third generation, it will be [a similar situation]."

For the Kawanas and their surimi business, it's the delicate balance between upholding the Japanese tradition and embracing American culture that's been key to keeping the company and the family going on strong for three generations.

Frank Kawana was taught by his parents to not stand out in the crowd, and to generally blend in with the others. Like most other Japanese-Americans at the time, the devastating events following the outbreak of WWII had a lasting impact on Kawana's life.

"As a nisei young boy of 8 years old, growing up in this atmosphere, I felt like I was a second class citizen," Kawana remembers. "How can someone explain to a young boy what's happening, except [think to] yourself that we were different, we're not with the American people."

He continues, "our parents -- in fact all isseis -- told the nisei children to behave, don't do anything that's gonna pull you away from everyone else...don't make waves because you can get in trouble. That's how we were raised."

In contrast, Teiji Kawana and his two brothers were taught to embrace their identity as Americans. Frank is especially proud of this philosophy that he's instilled in his children: "They don't take crap from anybody. They feel that they're American. If anybody says anything that's contrary to that, talking about the Japanese race or whatever, they put up a fight."

He's quick to note that remembering the family's Japanese heritage and traditions is just as important as well. "I made a point that [my sons] understand and know who our relatives are, know the history of the family, where they came from," he says.

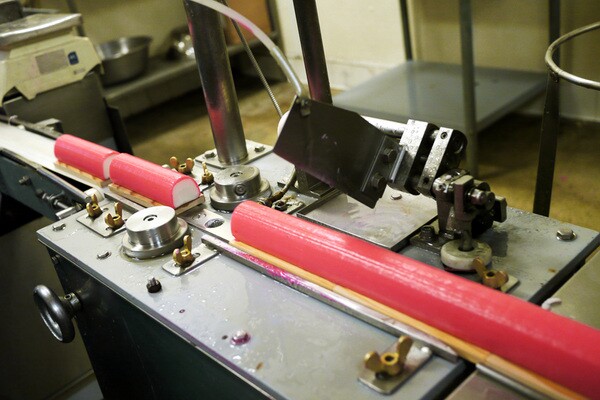

Frank Kawana knew early on that simply continuing the very Japanese tradition of kamaboko in America was't a good business model -- so he experimented. After such memorable failures as the Sea-lami and the Sea-sage -- salami and sausage made out of surimi -- Kawana hit big in the American market with another product, albeit something he did not invent: imitation crab. It's so ubiquitous now, you don't even think about how it ended up on the shelves of mainstream supermarkets everywhere. But if you must know -- Frank Kawana is the man responsible for bringing it to the United States.

Imitation crab was first developed in Japan in the early 1970s to counter the decline of kamaboko, which was not exclusive to America. As soon as he took a bite of the sample product, the astute Kawana knew that this was it -- this was what it will take to break into the American market.

After importing a custom-made machine from Japan, Kawana and JAC Creative Foods (Japan, Alabama [where his partners were based], and California) cemented its place in retail seafood history. Each year since they began manufacturing the product in 1981, his imitation crab business almost doubled, from $600,000 to $1.5 million, then $3 million, $7-, $15-, and $22 million.

"It was a very exciting time of my life, I finally was able to make something that was acceptable in the American market," remembers Kawana.

The success happened fast. Kawana realized that if he didn't expand his operations, companies from Japan will come and take over the market in the U.S. So he began sharing the technology with other companies, to saturate the market with U.S. made products, all with the Kawana stamp of approval. Within a few years there were 15 imitation crab manufacturers in the U.S., half of them from Japan, half from U.S.

But the product being mass-produced just wasn't the same. And Frank Kawana wasn't having it. As one of the leaders of the surimi industry in the U.S., he would speak at seafood conferences. "Japan has a 1000 year history in the surimi industry -- we are in year 7 or 8," Kawana remembers telling his competitors, "and you guys are killing the industry. You are making junk. If we don't start competing in the quality, this industry will not last 10 years."

Kawana sold the business within a decade. "At that time in 1989 the [imitation crab] industry in the U.S. was about $400 million," Kawana says. "Today it's about $400 million. It has not grown. And it's exactly what I had said. They kept making junk... that's the market they created, a market that's accepting junk. They killed the industry."

Today, the Kawana family business is alive and well. Now in the hands of Frank's three sons, the focus has shifted to yakisoba, renamed "stir fry noodles" for the American market. But they continue to manufacture the trusty kamaboko, for the shrinking Japanese population and, they hope, for new non-Japanese customers as well.

So did Frank make it a requirement for the Kawana children to go into the family business?

"I don't think he pushed us," says oldest son Teiji Kawana, who fell into the role naturally. "Just the fact that you've been around it for so long -- it's something that grows on you. It's not something where if you ask anyone who's college age whether they wanted to get into food manufacturing -- it's not glamorous."

The 79-year old Frank Kawana now prefers a hands-off approach to the empire that he had built from the ground up. "I told my sons, you do whatever you wish with to do with the company," he says. "If you feel you want to expand, go ahead. If you want to make it smaller, sell the business, close the business if you want." It's the same thing his mother had told him when he began working in the family business. "She let me do whatever I wanted to do, and that's the way I felt I should do for my children. And that's exactly what I told them."

But Frank, in his own way, knows that it will be a sad day when the time comes for the family business to close. "Deep down inside yes, I'd like for them to continue and be successful," he says. "Get the freedom of being a successful businessman and do what you want, have vacation, watch your children play basketball."

The longer a tradition continues, the harder it gets to see an end to it. Perhaps subconsciously, Frank leaves his sons with grand expectations to continue on the family legacy for many more generations to come.

"It's sad in a way for the person who has to close the business, the burden that they have when they close the door," says Frank, referring to businesses in Japan that have continued for 10 generations or more. "That's gotta be...it's like letting down your whole family, letting down generations of all the struggles that have been done before. And to be the one who has to close the business, that's gotta be a tremendous burden."

Teiji understands, though he realizes that it's not easy. "There's a certain amount of pride that we're a family run operation and we make products that serve the local community," he says. "Every year there's less and less of us in the food manufacturing side that still have that family tie. Not too many of us left."

He continues, "We've been making kamaboko for 74 years now. Ten years ago we always thought maybe we should push it to 100 years. That would be a good number. But it's tough, not too many family businesses go over a 100 years. We've got another 26 years to go if we wanna do that. I don't know if I have enough energy to do that. It would definitely have to go to the next generation."

Frank Kawana will be the first to say that Little Tokyo today isn't what it used to be. "You can count on your hand how many Japanese owned stores are there," he says. "All the nisei markets are all gone. Only things left are the oteras (temples)... we've lost the olden days of Little Tokyo atmosphere. It's sad."

But of all the things in Little Tokyo that remains, there's one thing -- perhaps the most important one for the Kawana family -- that he's forgetting: kamaboko. Walk into any market, whether it be Korean-owned or Japanese corporation-owned, and you will find a variety of kamaboko products, many of them proudly wearing the Yamasa label. Walk into any Japanese restaurant in the area, and they will undoubtedly offer kamaboko products in their menu.

Thanks to the Kawana family, that is one constant in Little Tokyo that we can hopefully rely on to be around for many (or at least a few more) generations to come.