The Hood: Comic Book Creator Brings Back Hero to Battle Thugs and Structural Racism in L.A.

I first met Stephen Townsend in 1993. Back then he was an idealistic 22-year-old comic book artist with aspirations fueled by the recent ’92 civil unrest that had cut a wide swath across South Central. A native of the Crenshaw district and a UCLA grad, Stephen became determined to contribute to the rebuilding of the city through his art—creating a counter-narrative to the economic stagnation and street-level violence besieging black neighborhoods in the ‘90s. These things were not abstractions for him. Shortly after the unrest, a friend and fellow UCLA grad was killed in a carjacking that made local headlines. For Stephen it was a pivotal moment.

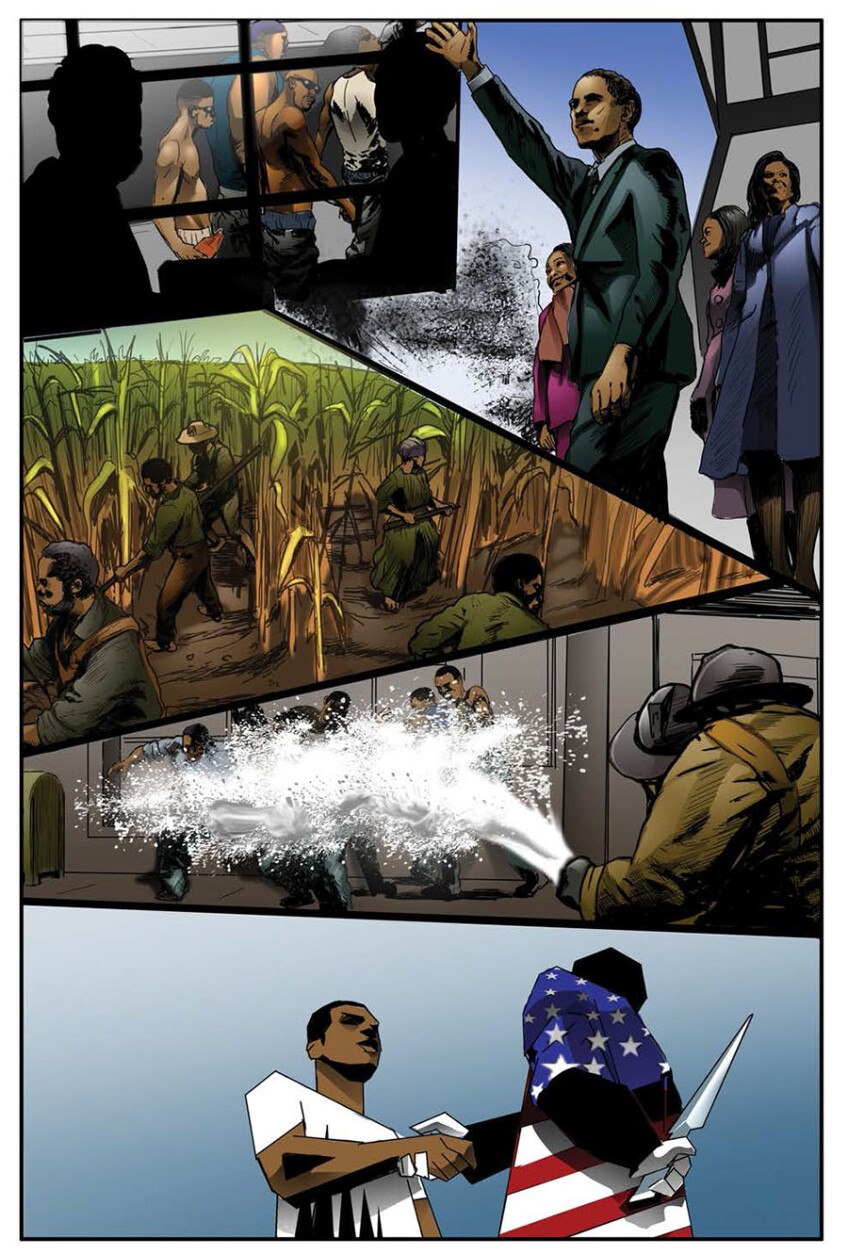

Enter the Hood, aka Anton, a modern superhero who goes about town intervening in violence and trouble as he strives to bring some measure of justice and peace to L.A.’s black inner city Stephen’s first issue published in ’93 introduced a youthful crimefighting figure patterned in some ways after Batman; human, but outfitted with clever technology to compensate for a lack of otherworldly powers (eschewing a cape, Anton shrouds himself in—what else?—a hood). Like Batman, Anton is also obsessed with righting wrongs after losing a family member to violence, in this case his older brother. And like youthful crusaders like Spiderman, the Hood is frequently beset with doubt about his own mission: is he doing the right thing, going about things the right way? Is he truly making a difference?

The Hood debut made enough of a splash to get Hollywood’s attention; Stephen landed a job with Dreamworks. His own life story arc as a hopeful young black man was suddenly encouraging, if not quite comic-book spectacular.

Twenty-three years and a few reality checks later, Stephen, now 45 and the father of two teenagers, is reintroducing The Hood—call it the millennial version. Times have changed. The protagonist and his signature garb is the same, as is his grassroots crimefighting mission in South Central. But the world of the Hood has gotten more complicated. Anton is no longer a solo act; he works with a whole community support team of social justice advocates that includes a woman. Things have gotten more complicated morally. The line between good and bad guys in the neighborhood is less sharply drawn; there is another crimefighter on the scene, a rough doppelganger to Anton, named the Midnight Mercernary. Anton’s late father is an LAPD detective killed in the line of duty, and his mother worries about losing both sons to violence.

Some of the story elements echo Stephen’s own life. His father is a former LAPD detective who also worried about violence—not on the streets, but violence within police culture directed at people of color. When Stephen was a teenager and started driving, his father gave him a card on which he wrote a note explaining to any fellow cop who might stop Stephen that he was a good kid who shouldn’t be mistreated. It was a preemptive strike against racial profiling that Stephen’s dad understood all too well. The son admits that the note saved him more than once.

Reflecting the more complex challenges facing black folks in the Obama era, the enemy in this ‘Hood’ (subtitled ‘A Change From Within’) is not merely thugs and criminals. Villains are far more nebulous--a permanent lack of opportunity, ethnic infighting, structural racism. “Unfortunately, it feels like we’ve come full circle,” says Stephen. “We are where we were in 1992, though in some ways even worse.” That doesn’t mean this isn’t a fun read. Like the first effort, the story is as full of action as reflection, shot through with a kind of broad, buddy-movie action-hero humor that ensures the proceedings never get too preachy or serious. Hip-hop lyrics are a kind of Greek chorus that punctuate the story’s more dramatic moments. The entertainment value is bolstered by the gorgeous art and lettering—another team effort coordinated by Stephen that included letter artist Janice Chiang. Stephen does the writing duties.

It’s a far cry from the first issue in ’93 that Stephen created in nine months by himself, entirely by hand. After putting out a second issue in ‘94, he became immersed in work and then family but never lost his desire to pick up the project at some point. In 2008 he unexpectedly got that opportunity when the games company he was working for went out of business and he found himself unemployed for more than a year. He reconnected with an agent who had supported his original vision who had since become a producer. That producer pitched in some money to help revitalize the Hood, and Stephen launched a Kickstarter campaign that netted close to $5,000. Not a fortune but enough to enlist an artist, letterer and colorist. This time out, Stephen focused solely on writing, but the relaunch took about four years to finish. The project was a revelation to Stephen in more ways than one. “In the ‘90s I got sucked into whole Hollywood thing, when initially all I wanted was to be a comic book writer,” he says. “Writing is what I wanted to do most.”

He admits that the re-emergence of a black superhero with community-based support is pretty timely. “It’s an interesting moment to promote this hero of ground level black change-- that’s really what Black Lives Matter is about,” he says. The February re-launch is also timely for him personally: Anton was never just a comic-book character to him, he says, but a part of his determination to clarify and fulfill an artistic calling focused on improving conditions in the place he grew up. That’s far easier said than done. Stephen admits that he doesn't see a simliar determination to make change, through art and other means, amongst young black folks these days. Part of it is the shift in hip-hop away from political statements to party culture, the difference between Public Enemy and Drake. He also says that times are simply tougher for black men; they are arguably less likely to succeed now than they were 25 years ago. “Tupac once said that once young black men get into their 30s and older it’s harder for them to matter because they get compromised—in jail, or working and absorbed by the system,” he muses. “Youthful revolution is key.”

Though Stephen got absorbed in a mostly positive system of work and family, he’s glad he came up for air. He’s not complaining about his current gig at Mattel—far from it—but it’s clear that isn’t what gets him going. Unemployment, the boon of black men everywhere, seems to have been the best thing to have happened to him. He’s already begun work on another issue of "The Hood," which fleshes out a villain alluded to in this issue; he hopes it'll take a year or so. Much depends on the response to this latest issue, which is available for downloadingand purchase online. He’s also working on a distribution deal to get hard copies into bookstores and other places—something made tougher by the advent of the digital age. But whatever the challenges, his commitment to the project has been revived, maybe permanently. Stephen is especially excited about enlisting his son, also an artist and video game enthusiast, in the next book.

“I returned to what I was passionate about,” he says. “I had to find my creative muse again.” Mission accomplished.