Civilian Conservation Corps, Racial Segregation, and the Building of the Angeles National Forest

The Angeles National Forest, granting Los Angeles County 70% of its open space, is today considered the most accessible and popular "playground" in Southern California. Its prominent recreational legacy is rooted in the efforts of work relief programs from the Great Depression, notably the labor of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC).

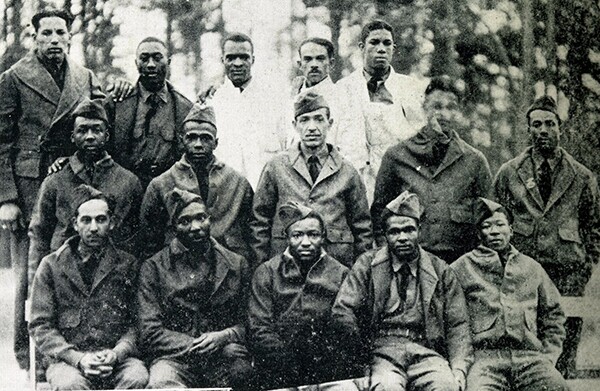

Obscured in the Angeles' history is the role that all-African-American CCC camps played in the development of forest infrastructure that continues to be enjoyed today by millions of visitors to the San Gabriel Mountains.

The CCC was the product of the Emergency Conservation Act of 1933, the first major work relief act passed as part of President Roosevelt's New Deal programs. Aimed at relieving the dire levels of unemployment during the Great Depression, and building the country's forest resources, the Act provided for the creation of the CCC to hire unemployed young men to develop conservation infrastructure in the national parks and forests. A crucial amendment to the bill stipulated: "That in employing citizens for the purposes of this Act no discrimination shall be made on account of race, color, or creed."

Although young men of color were secured an opportunity to serve in an integrated Corps under this provision, discriminatory practices would soon disfigure the promise of equality. By July 1935, bowing to pressures that included what Olen Cole, Jr. identified in "African American Youth in the Program of the CCC in California, 1933-42," as "anti-pathy from local communities, racist attitudes in the U.S. Army, and the usual racial fears," the inclusive policy was impaired. CCC National Director Robert Fechner instructed all CCC districts in the country to separate African-American and white corpsmen into different camps.

In the fall of the same year, two all-African-American CCC companies were established in Los Angeles County. One of them, Company 2924-C, also known as Camp Castaic, was allocated to the Angeles National Forest, a region that contained over a dozen all-white CCC camps. Thomas L. Griffith, Jr., President of the the Los Angeles Branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), wrote to President Roosevelt criticizing the segregationist policy. Fechner, replying on behalf of the President, was defensive, "This segregation is not discrimination and cannot be so construed." He made his loyalty to the ways of Jim Crow clear:

The negro companies are assigned to the same types of work, have identical equipment, are served the same food, and have the same quarters as white enrollees. I have personally visited many negro CCC companies and have talked with the enrollees and have never received one single complaint.

Despite the indignation provoked by Fechner's Jim Crow policy from civil rights activists like Griffith, Jr., segregation was a permanent fixture for the men of Camp Castaic. The approximately 150 young men worked eight hours a day, five days a week on forests improvements, primarily working on different types of routine projects, like constructing and maintaining campgrounds. Daily efforts could also be extend to the development of park roads, fire breaks, and hiking trails.

In contrast, white camps in other canyons of the Angeles National Forest had the opportunity to work on special priority projects. The CCC men of Dalton Company were assigned to construct twenty facilities for the new San Dimas Experimental Forest, a field laboratory for ecosystem and watershed studies that still exists today.

Another company, Camp Coldbrook, not only worked on the largest campground project in the state, but also dispatched their fire suppression crews during the fire season of 1936, logging more hours firefighting than any other state camp. CCC men were also recruited to build the Southern California section of the Pacific Crest Trail, the famed 2,650 mile hiking path that would stretch from Mexico to Canada.

In addition to the imbalance of labor opportunities, few African-American corpsmen could climb the ranks within the CCC's administrative hierarchy. This inhospitable environment pervading the chain of command was a direct result of the prejudiced beliefs of Fechner. In a letter to Fechner on September 26, 1935, from Harold L. Ickes, the Secretary of the Interior, Ickes rejects the CCC director's low opinion of African-Americans in supervisory positions:

I have your letter of September 24 in which you express doubt as to the advisability of appointing Negro supervisory personnel in Negro CCC camps. For my part, I am quite certain that Negroes can function in supervisory capacities just as efficiently as can white men and I do not think that they should be discriminated against merely on account of their color. I can see no menace to the program that you are so efficiently carrying out in giving just and proper recognition to members of the Negro race.

Although Ickes supported the initiative, the placement of African-Americans in administrative positions gained little traction. Calvin G. Gower, in a 1976 article for The Journal of Negro History, acknowledged that "the only breach in that policy of any proportion, and it was considerable, was in the appointment of black educational advisers." Outside of these specific advisory roles, Fechner's systemic resistance to African-Americans in leadership roles held firm throughout the program's nine-year run.

The nation's entry into World War II and a subsequently rebounding employment market led to the termination of the CCC program by Congress on July 1, 1942. Through its duration, close to 250,000 African American corpsmen served in nearly 150 segregated camps that spanned the forest lands of the United States. The contributions of all-African-American camps were vital to the development and maturation of the nation's major parks and conservation infrastructure.

The heritage of the Angeles National Forest belongs in part to these African-American corpsmen, whose lesser-known efforts helped build and protect the forest rising above Los Angeles.