A Kosher Slice of Pico-Robertson

Martin Krieger was brought up in an orthodox shul in Brooklyn, New York. Even though he was reared in what he calls the culture of Judaism, he says "my grandmother was more important than God." Today, he is the Professor of Planning in the Price School of Public Policy at the University of Southern California, with volumes of research andphotographic and audio documentation of Los Angeles.

It all started one day on a drive through his neighborhood down La Cienega Boulevard in Pico-Robertson, when he came upon a hubab synagogue crowd filled with dozens of multi-child carriages. "I said, 'This is too terrific,'" he recalls, "it's very obviously Jewish. If you're here on a sabbath or Friday night, it's obvious." With years of knowledge on the nature of cities, he thought that the neighborhood should be documented -- and so he went on to do it himself.

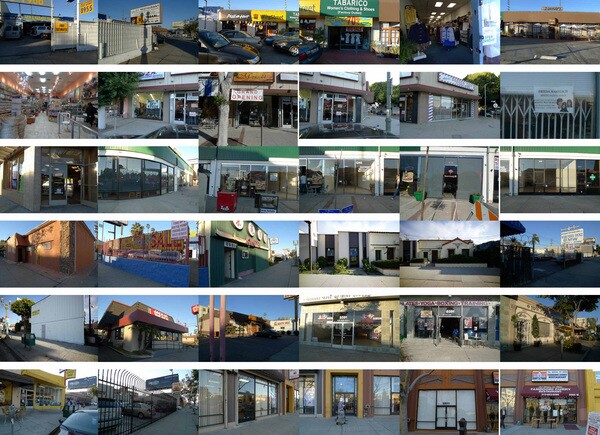

Krieger's research on the Orthodox Jewish enclave in Pico-Robertson, supported by a grant from the Haynes Foundation, surveys every store and residence on Pico Boulevard, from east of La Cienega to west of South Beverly Drive; and on Robertson Boulevard, from north of Wilshire Boulevard and down to the 10 Freeway. The images are set-up in a montage that takes the viewer up and down the street, with a panoramic view of the entire area when the image is seen as a whole.

His method, which he calls Urban Tomography -- also the name of his book -- involves systematically documenting a subject from multiple angles. "Photographically and orally, you want to get as many aspects as you can -- slices," explains Krieger. "The emphasis is not a single image. You integrate them by looking at them together."

Accompanying the photomontage is a map that documents two key focuses of his research: mezuzahs, decorative pieces of the Hebrew text usually affixed to a doorstep, and the varying degrees of kashrut, the set of Jewish dietary laws as defined by different certifying bodies. According to Krieger, most Jews in the Pico-Robertson consider a stamp from the Rabbinical Council of California (RCC), to mean a higher level of kashrut.

The hyper-detailed research on Pico-Robertson shows an incredible density of kosher food in the area, from simple bakeries to more surprising ones like a (now defunct) particular location of Subway, which did not serve meat and cheese together according to kosher rules. The map also includes indications of Farsidic Jewish language and kosher eateries.

In Pico-Robertson, Krieger notes an acute difference from the Judaism he grew up with. "My synagogue would probably not be approved by most of these orthodox shuls," he says, "and a modern synagogue [in Pico-Robertson] would say 'oh, they're ok.'" That's because the Orthodox Jewish community here, made up of more than 80,000 people with 25 Orthodox synagogues and 15 other service organizations lining the streets, originates from a different chapter in the history of Jews in America. "This," Krieger explains "is the transplantation of post-World War II Jews who survived [the Holocaust] in Eastern Europe, whose rabbis came here and re-established the kinds of observance that my grandparents left when they came to the U.S."

According to Krieger, that is Judaism from 19th or 15th century Europe, which is far more conservative when it comes to religious observance and interpretation. "The rabbi has more authority here. The questions of how kosher you are are more articulated," he says.

Jewish enclaves like his childhood home in Brooklyn, and even in Boyle Heights, which was the center for Jewish life in Los Angeles from the 1920s to 1960s, were far more assimilated into the general culture, whereas the Orthodox Jews in Pico-Robertson -- comprised mainly of ashkenazi and sephardic -- define themselves against modernity. "They think of themselves as more authentic, which is crucial," says Krieger.

Then there are the Persian Jews. Following the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, tens of thousands of Persian Jews immigrated to Los Angeles. L.A. has always had substantial amount of Jews, "but this is very different," Krieger says. Many brought with them from their home country an idealized view of what Western life would be like, which created a wholly unique set of characteristics to their neighborhoods.

"Everybody talks about Los Angeles as if it's a vast, undifferentiated place -- they always talk like that -- but it's not true at all. It's a highly differentiated, highly marked place," says Krieger. He adds, "remember if you live here, you don't live in Los Angeles, you live in Pico-Robertson, and that's a big fact. These peoples' lives are focused here. They make work downtown, but this is it, this is mecca -- a little funny word to use."

While Krieger has immersed himself in Jewish history in America and this unique Orthodox Jewish enclave, he is far more concerned and excited about his process of documenting the city. "You gotta get out of your office, you gotta get off of Google Maps and get out and look," Krieger says. "I see this as an archive that people will be able to use 30 or 50 years from now." Inspired by Charles Marville, a French photographer who famously documented the city in the 1850s, Krieger sets his sites on the long haul reward rather than publishing a book. "I'm fairly senior in my career, I've published about eight books. I don't worry about those kinds of issues. Also I'm very assiduous -- if i say i'm going to do something, I do it."

Citing the needs of qualitative measures and field work in city studies, Krieger hopes that many years from now, people will be able to use his research to remember the history of distinct migrations of people in the city. "Maybe it will be the same 20 or 35 years from now," Krieger says, "but I just don't believe it, because cities are not that stable in this way."