Beyond Gene Autry: The Making of the Singing Cowboy Myth

For lots of people — especially Southern Californians — the nickname “The Singing Cowboy” conjures memories of and nostalgia for Gene Autry.

But while Autry left an indelible mark on SoCal with his film career (and patronage of L.A.’s Autry Museum of the American West), this second-generation Texan wasn’t the only celluloid cowboy of song.

Nor was he the first.

Born in 1907 as Orvon Grover Autry, the star of recordings, radio, stage and screen essentially replaced John Wayne as Republic Pictures’ singing cowboy in a starring role.

Learn more about the origins of country music in this trailer. Watch now.

Wayne played Singin' Sandy Saunders in 1933’s “Riders of Destiny”— but it’s not his voice you hear. He only mouthed the words to such tunes as "Blood on the Saddle," which were actually sung by Smith Ballew.

From 1933 to 1935, the actor who was to become “The Duke” shot a few more musical westerns for Monogram (via Lone Star Productions)— this time voiced by the director Robert Bradbury’s son, Bill. But Wayne wasn’t happy with the charade, and Republic Pictures wanted to get an actor who could portray a cowboy and sing.

Even Gene Autry didn’t exactly fit the bill right away: He wasn’t much of a horseman, and he needed acting lessons. He didn’t seem to have enough “virility” to be believable as a cowboy (though, in the end, his lack of sex appeal likely cemented his success).

Autry was, however, an improvement over Wayne and Wayne’s predecessor, Ken Maynard. An accomplished horseman, rodeo performer and trick rider, Maynard holds the distinction of being Hollywood’s very first singing cowboy — in the 1929 film “The Wagon Master.”

Maynard essentially paved the way for Autry’s rise to stardom. It was the Maynard film “In Old Santa Fe” that gave Autry a break — though, at the time of its release, in 1934, Autry’s participation in the film was uncredited.

By the time “The Singing Cowboy” feature film hit theaters in 1936, Autry wasn’t just a western movie star — he was one of the biggest movie stars there was.

His meteoric rise, however, didn’t come out of nowhere. And Hollywood screenwriters and composers didn’t invent the singing cowboy archetype out of nowhere, either.

Unknown to many, real-life cowboys on cattle drives from Texas into western states actually sang from the 1870s to the 1890s.

Not only that — but they had to sing.

According to pioneering musicologist and folklorist John A. Lomax, if a cowboy couldn’t sing back then, he wouldn’t get hired in the first place. Those who led the drives wanted melodies that would be ideal to ride by (and would lull the cattle to sleep at night).

“It was natural for the men to seek diversion in song,” Lomax wrote in his seminal 1910 songbook “Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads,” which preserved the genre for Hollywood to later discover.

And if they didn’t know any trail songs, Lomax discovered, they’d make some up on the spot — usually to familiar melodies, sometimes based on Anglo-Saxon (a.k.a. British and Irish) folk songs.

These cowboys rode along the Utah, Navajo and Santa Fe Trails of the Great Western Cattle Trail “with a song on their lips,” and they gave voice to “the freedom and the wildness of the plains.”

After all, as Douglas B. Green’s 2002 book “Singing in the Saddle” states, cowboys were no different than any other men who worked in isolation for extended periods of time.

“A tradition of song by or about those men and their work develops,” Green wrote. “Sailors, loggers, railroad workers, boatmen, miners and others all have musical traditions.”

But at the turn of the century, those romantic days of the West were changing.

The spread of railroads and the permanent settlements of ranchers, homesteaders and farmers rendered cattle drives obsolete. Fences and corrals encroached upon their formerly “trackless open prairie.”

When Lomax recorded them in the field — sung by real-life cowboys in the back rooms of saloons — sagebrush serenades like “The Old Chisholm Trail,” “The Buffalo Skinners,” and nearly every cattle call were already almost extinct.

Listen to the "Old Chisholm Trail" and "The Buffalo Skinners" in this recording from Roger McGuinn's "Folk Den Songs." This is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

But with his musicology project, Lomax helped popularize the sentimental songs that depicted an idealized version of “the wild, far-away places of the big and still unpeopled West.”

After all, the sentiments themselves had universal appeal.

Isolated and lonely, these lovelorn cowboys had made a sacrifice in order to scratch the itch to roam: They left behind the women they loved.

“Come all you young cowboys, I’m tellin’ you true,

Don’t depend on a woman – you’re beat if you do;

And when you meet one with bright golden hair,

Just think of this cowboy that will die in despair.”

— “The Lovesick Cowboy,” as published in “Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads” by John A. Lomax

Not just their sweethearts, as characterized in songs like “The Gal I Left Behind Me” — but their mothers, too.

“On mother’s advice you can depend

And when she’s gone you’ve lost your best friend.”

— “Speaking of Cowboy’s Home,” as published in “Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads” by John A. Lomax

In the dwindling days of the Victorian era, Americans went crazy for the mythology — including vaudeville shows starring singing cowboys (including Wild West shows like those starring “Buffalo Bill” Cody) — and sheet music of their songs.

And that was just in time for the rapidly developing commercial music industry to capitalize on and commercialize on the heartbreak behind such artful tunes as “Home On the Range.”

Listen to "Home on the Range" in this recording from Roger McGuinn's "Folk Den Songs." This is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

So, the singing cowboy really first entered the mainstream through the song, and not the pictures.

The image, of course, did help — as Texan singer Carl T. Sprague discovered when he scored the first-ever hit cowboy record with “When the Work's All Done This Fall” in 1925.

Called “The Original Singing Cowboy,” Sprague was the first such singer to actually work as a cowboy and sell lots of records — and since he lived the part and dressed the part, according to the Western Music Association, he used the image to market his recordings.

It wasn’t long before the “Tin Pan Alley” teams of professional writers began to crank out popular standards that tapped into cowboy lore.

Which brings us back to Gene Autry — who’d made a name for himself in recorded music and on radio long before he’d hit the silver screen in a set of spurs. History tells us that he “wrote” nearly 300 songs — but in some cases, it turns out he’d purchased the copyrights from the actual songwriters.

Were those songs from “real” cowboys who’d written dreary tales of the trails in song? We’ll probably never know.

But historical accounts confirm that he’d begun singing as a schoolboy and eventually carried a guitar almost everywhere he went — though he couldn’t read music and could only play by ear. He started to get some attention for his musical ability after dropping out of high school to work as a telegrapher for the St. Louis-San Francisco Railroad (a.k.a. “Frisco Railroad”).

There, both his customers and coworkers would encourage him. He’d use his breaks from work (and his employee rail pass) to try his hand as a professional singer in big cities like New York and Chicago. At the time, rural people who’d moved into cities wanted to hear examples of “their” music. And Gene Autry delivered what they were looking for in spades, first as the “Oklahoma Yodeling Cowboy” on Tulsa’s KVOO radio (“The Voice of Oklahoma”).

Hear Dolly Parton discuss the attraction of country music on this clip.

Autry made his breakthrough recordings on October 29, 1929 — a.k.a., Black Tuesday, the day of the stock market crash that officially kicked off the Depression.

You might think that he’d been cursed by the worst timing ever, but it was just the opposite. In fact, Autry’s success as a best-selling recording artist is inextricably linked to the Great Depression, when “country & western” was still considered “hillbilly music” and white, working-class southerners were stigmatized both culturally and socially.

Working-class families — who so devastatingly experienced the hardship of the Great Depression — comprised the heart of Autry’s audience. And somehow, despite financial destitution, they managed to scrounge up enough money to buy his records.

By 1929, most movie studios had already abandoned silent film and were figuring out new ways to incorporate sound into their “talkies.” And the Great Depression was still in full swing when Herbert J. Yates formed Republic Pictures in 1935.

In the 1930s, California was seeing an influx of migrants from Oklahoma’s Dust Bowl — then known pejoratively as “Okies” — and you have to think that Hollywood execs like Yates must’ve put two-and-two together that this underserved demographic might clamor for a gentle cowpoke like Gene Autry.

For Autry’s starring debut in a feature, 1935’s “Tumbling Tumbleweeds,” Republic Pictures leveraged his musical popularity on radio to sell the film, with such taglines as “Radio’s Singing Cowboy Takes to the Saddle in a Musical Action-Drama” and “The Singing Idol of the Air Now Becomes the Troubadour of the Trail.”

Though it took only one week to make, “Tumbling Tumbleweeds” produced one of Autry’s all-time most popular songs, “That Silver-Haired Daddy of Mine.” And five weeks later, Republic Pictures released another Autry feature: “Melody Trail,” in which Gene Autry portrayed a character named “Gene Autry” for the third time — a tradition he’d continue through to his final film, 1953’s “Last of the Pony Riders.” He first played the character Gene Autry in 1935’s “The Phantom Empire.”

But Autry was never a real cowboy. Working cowboys never yodeled the way that he did unless they were immigrants from Alpine regions. (The characteristic “Yodelayheehoo” was more authentic to the Von Trapp family in “The Sound of Music” than to the cattle drives of the Old West.)

And once Autry emerged into stardom and came to exemplify the image, the singing cowboy was no longer “lovesick.” Any hanky-panky would disgust the young boys in the audience, so the only companion the singing cowboy would kiss henceforth was his horse.

The singing cowboy’s visual image, too, had evolved greatly from the rough-and-tumble nomad who used his saddle as a pillow. As author David Rothel points out in his book “The Singing Cowboys,” a singing cowboy could wear “a much fancier shirt” than a non-singing one.

What helped the image of the cowboy become mythic was that Autry chose to extend the fashion choices to his off-screen appearances. According to author Holly George-Warren in her 2007 book “Public Cowboy No. 1,” Autry “vowed to always dress Western in public” and was fully invested in his “buckaroo trappings.”

All told, Autry shot 93 movies and earned five stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (for radio, recording, motion pictures, TV, and live performance) as “America’s favorite cowboy.”

But it wasn’t always a smooth ride.

Even with hit films under his belt, Autry was still making more money in music than in film. The more that the cowboy star tried to leverage his box office pull with Republic Pictures in contract renegotiations, the more the studio searched for possible successors.

That turned out to be a good thing — because during a broadcast of “Gene Autry’s Melody Ranch” on CBS Radio Network, Autry enlisted for service in World War II.

That move opened the door for Roy Rogers to step up and into the spotlight.

While Autry was flying large cargo planes as a flight officer with the Air Transport Command in the China Burma India Theater from 1943 to 1945, Republic sold Rogers on his good looks and family-friendly appeal, with a sound that was smoother than the “hillbilly” music of yore.

Rogers ultimately became “King of the Cowboys” — nicknamed after the 1943 Republic Pictures film of the same name.

Like Autry, Rogers (born Leonard Slye in Ohio) began his performing career as a child — and in music, not film. At just barely 20 years old, he was invited to join a singing group called The Rocky Mountaineers, which evolved into the hit-making trio Sons of the Pioneers in 1934. In 1936, the vocal group scored a career-making smash with the song “Cool Water.”

In 1937, Rogers snuck into a singing cowboy “cattle call” and got himself signed with Republic Pictures — probably as part of its attempt to hedge its bet with Autry. By then, Rogers had already appeared on film as a member of Sons of the Pioneers in “The Old Corral” — starring Gene Autry, no less — wearing a black hat and singing a prison song.

But he’d been credited under his birth name and didn’t become “Roy Rogers” until he inked his contract with Republic. After that, he made sure audiences would never forget his name, appearing as the character named “Roy Rogers” in every film from 1941’s “Red River Valley” to 1951’s “Pals of the Golden West.”

When Gene Autry returned from WWII in 1946 and resumed his movie career, he realized not only that he’d been somewhat replaced — but also that the days of the B-movie (or “serial”) western were numbered.

Fortunately, Autry didn’t hang his hat on his future as a movie star. He began to diversify his business — first by becoming one of the first major stars to make the leap from the big screen to television in 1950.

Of course, Rogers would follow suit the following year with “The Roy Rogers Show,” which ran for six seasons and launched its Dale Evans-penned song “Happy Trails” into the country music canon.

All in all, Roy Rogers shot 87 musical westerns — 35 with Dale Evans, his real-life wife and “Queen of the West” — falling short of Autry’s 93.

There were other differences, too. For instance, Autry’s movies were generally set in the present, while Rogers’ took place in the past — both reinventing history in their own ways.

But there was even more that linked the two to each other.

They each rode their famous horse companions — Autry on Champion, the “World’s Wonder Horse,” and Rogers on his palomino, Trigger, “The Smartest Horse in the Movies,” and Evans on Buttermilk, a Buckskin gelding.

Like Autry, Rogers liked to get “all duded up.” In the early 1950s, he and his wife became two of the best customers of famed costumer Nudie Cohn and his Nudie’s Rodeo Tailors business, which had been “embellishing the west” since opening in North Hollywood in 1947. Cohn’s long-running relationship with Rogers and Evans eventually paved the way for him dressing such other stars as Elvis Presley and Cher.

As his daughter Cheryl Rogers-Barnett described in her memoir “Cowboy Princess,” Rogers reportedly wanted the kids high up in the cheap seats to be able to see him on stage. And since rhinestones do look great under spotlights, so emerged the “Rhinestone Cowboy,” riding out on a horse in a star-spangled rodeo

In 1967, Rogers bought a ranch outside of Victorville so he could, according to The Los Angeles Times, skeet-shoot and breed and train racehorses. (He also planted grapevines in the 1960s.)

He and Dale Evans also owned the Roy Rogers Double R Bar Ranch, located along the Mojave River off old Route 66, until their deaths in 1998 and 2001, respectively.

Since 2015, a stunt rider named Jim Heffel has owned Roy Rogers Double R Bar Ranch and rented it out for weddings, film shoots and other special events. It’s technically for sale — but until it sells, it’s business as usual.

Of course, Gene Autry had already beat Roy Rogers to the punch, at least in terms of ranch ownership, when in 1952, he bought the former Monogram Ranch in Placerita Canyon (just north of Los Angeles) and renamed it “Melody Ranch,” after his hit radio and TV shows.

Tragically, Melody Ranch burned to the ground in a wildfire in 1962, though Autry retained ownership of it until 1990 when he sold the movie ranch to the Veluzat brothers, who eventually rebuilt it to its original specifications.

Beyond Melody Ranch, Autry far outpaced his fellow singing cowboys as an entrepreneur, forming his Golden West Baseball Company and buying a stake in the California Angels (now the Los Angeles Angels) Major League Baseball team in 1961. His Golden West Broadcasters company-owned across the country (including, for a time, LA’s own KTLA). The Gene Autry “brand” could be seen on nearly every piece of merchandise you could imagine (not the least of which were lunchboxes).

Both Autry and Rogers opened their own museums, but it’s the Gene Autry Western Heritage Museum, which opened in 1988, that Southern Californians can still visit. It’s now known as the Autry Museum of the American West (see below for other places of interest that are open to the public).

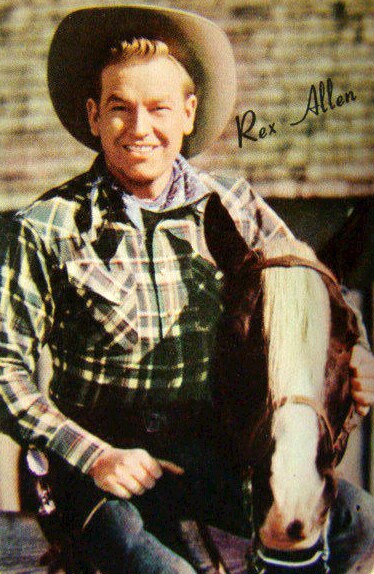

There was one more singing cowboy to follow in the footsteps of Gene Autry and Roy Rogers at Republic Pictures — “the last of the great singing cowboys,” Rex Allen, who made the last singing western, “Phantom Stallion,” in 1954.

Also known as “The Arizona Cowboy,” Allen continued performing — recording, touring the rodeo circuit, and even starring in the TV show, “Frontier Doctor” (produced, appropriately, by Republic Pictures).

What would’ve happened if Allen had gotten his start earlier in the game?

The era of the “singing cowboy” was just so short — though its legacy has lived on longer than anyone could’ve expected.

The era’s last cowboy with a song in his heart to survive was also the first of his kind — Herb Jeffries, who made movie history as the silver screen’s first black singing cowboy. Of mixed European and African descent – including a reportedly Ethiopean great-grandmother – the light-skinned Jeffries made a name for himself as “The Bronze Buckaroo,” starring in four “black” (or “dark” or “race”) westerns from 1937 to 1938.

At the time, black actors were typically relegated to playing subservient roles on screen — but Jeffries, who’d learned to ride on his grandfather’s dairy farm in Michigan, became “the African American answer to Gene Autry, Roy Rogers and other white singing cowboys,” as The Los Angeles Times called him in a 2014 obituary.

The man who would go down in history for singing “I’m a Happy Cowboy” died at the age of 100.

And who did Roy Rogers and Gene Autry consider the best cowboy singer of all time? That honor goes to Texan Eddie Dean, the first singing cowboy to appear in color (technically, Cinecolor) in a starring B-western role.

Born in Texas as Edgar Dean Glosup, he starred with his horse Flash in 1946’s “Tumbleweed Trail” and went on to found the Academy of Country Music and get inducted into the Cowboy Hall of Fame and the Western Music Association Hall of Fame.

Can't get enough of these celluloid cowboys?

Here's are few places to go and find the legacies they left behind:

- Autry Museum of the American West, Griffith Park, L.A. for exhibits on Gene Autry, the Cowboy Gallery, and the monthly Western Music Association Showcase, which takes place on the third Sunday 12-3 p.m.

- Walk of Western Stars, Downtown Newhall to peruse past honorees including Roy Rogers and Dale Evans, Tex Williams, Rex Allen, Eddie Dean, Tom Mix and Gene Autry.

- Santa Clarita Cowboy Festival, Old Town Newhall for modern-day cowboy balladeers and occasional tours of the once Autry-owned Melody Ranch offered by Newhallywood Tours.

- Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society at Heritage Junction, Newhall to see the Gene Autry-owned Mogul Engine 1629 (circa 1900) once used at Melody Ranch and to find out more about past singing cowboy film shoots in the Santa Clarita area.

- Valley Relics Museum, Van Nuys for memorabilia from The Palomino Club (where Eddie Dean frequently performed) and historical artifacts of Nudie Cohn’s tailoring career.

- Day of the Horse annual festival, Chatsworth which will place you in extremely close proximity to Gene Autry’s former home on Andora Avenue and Roy Rogers and Dale Evans’s former home on Trigger Street (please respect the privacy of current residents).

- Apple Valley Legacy Museum at High Desert Community Foundation, Apple Valley for displays on Roy Rogers and Dale Evans and the newly repainted statue of Trigger that used to stand outside of the Roy Rogers and Dale Evans Museum in Victorville (moved to Branson, Missouri in 2003, closed in 2009).

- Museum of Western Film History, Lone Pine for exhibits on Gene Autry and other singing cowboys.