The Foreclosure Crisis and Its Impact on Today's Housing Market

City Rising is a multimedia documentary program that traces gentrification and displacement through a lens of historical discriminatory laws and practices. Fearing the loss of their community’s soul, residents are gathering into a movement, not just in California, but across the nation as the rights to property, home, community and the city are taking center stage in a local and global debate. Learn more.

In recent years, the American public has been treated to a number of films about the 2008 housing crisis: the insightful documentary “The Queen of Versailles”, the dark, simmering “99 Homes”, and the Oscar nominated “The Big Short” to name a few. For all the critical acclaim bestowed upon each, with the exception of a couple of short scenes from “The Big Short”, none portray the travails of working-class black and brown homeowners or the ways in which a historically racially biased system of home financing contributed to the 2008 debacle.

Nearly a decade after the housing crisis, public policy professionals and academics have worked to unravel the complex factors that led to the catastrophe and why minorities and women proved particularly vulnerable. The intersection of racially constructed housing markets; changes in banking and housing finance, notably the securitization of mortgages; and the proliferation of subprime loans explain why the 2008 crash devastated communities of color.

University of California, Davis sociologist Jesus Hernandez, who grew up in Sacramento’s Oak Park neighborhood, has spent years studying the housing crisis nationally, but also the more specific experience of metropolitan Sacramento homeowners. In addition to the devastating losses of private homes, the housing bubble cost the city dearly. According to the California Reinvestment Coalition, in 2007 Sacramento residents faced with foreclosure lost, in addition to their homes, $54 million collectively. Administrative costs related to foreclosure extracted $40 million from city coffers, and the city’s Gross Municipal Product suffered as well; one study estimated losses of $1.73 billion in GMP. Cascading social costs resulted, including increasing numbers of vacant buildings, rising crime rates from squatting and reduced revenues from property taxes, physical deterioration of neighborhoods and housing stock, and schools squeezed ever tighter for already insufficient funding.

In numerous post-mortem analyses of the housing crash, subprime loans emerged as the culprit. Such loans feature higher interest rates often referred to as adjustable rate mortgages (ARM), rather than fixed rates mortgages which remain locked in at their agreed upon level. From 1994-2003, subprime loans increased 25 percent annually in what amounted to nearly a ten-fold expansion in nine years. While subprime loans did contribute to increasing numbers of minority homeowners, it did so in ways that left individuals and families more financially vulnerable than their white counterparts.

Even worse, more predatory subprime loans featured “teaser” rates that started lower but increased within a year or two. As with any financial product, subprime loans can work well facilitating homeownership for those black and brown households who were denied traditional financing. However, these same families disproportionately fell victim to the proliferation of subprime housing finance. The 2008 housing crash demonstrates how such products can be perverted and borrowers exploited particularly working-class black and brown homeowners.

While the narrative of personal responsibility frequently arises in discussions of the housing collapse, long-term structural issues go further to explain why the 2008 crisis ravaged communities of color. The idea that these communities were somehow less responsible does not fully square. Yes, undoubtedly some borrowers were overextended and irresponsible. However, plenty of better off homeowners, many of them white and upper class, walked away from their financial obligations when it suited them. In 2010, the New York Times reported that homeowners “with less lavish housing are much more likely to keep writing checks to their lender,” than their wealthier counterparts, who when faced with excessive losses, simply defaulted. Furthermore, delinquency rates on “investment homes”, properties purchased for financial return rather than residency, where the mortgage started at $1 million, rose to 23 percent in 2010, wrote David Streitfield.

Hernandez, who spoke with KCET by phone, raises a second issue: the ethical responsibility of the real estate industry. “I don’t know of one homeowner who approved his own loan. If you want to talk about responsibility, lenders are responsible for vetting the client,” he pointed out. Brokers and other industry professionals jettisoned such responsibilities, shirking their fiduciary obligations. Talk of personal responsibility elides this failure by professionals. “Nobody held the industry accountable; they were the connection between money and property. They used their network [for personal gain] and so that fiduciary responsibility got lost.”

As one can tell, the housing crisis and its effects are complicated; they do not boil down to simple explanations of personal responsibility and free markets. Instead, as Hernandez told us in his interview, the crisis was the result of decades of racially prejudicial policies that impacted working and middle-class brown and black homeowners unfairly and unequally. In the end, the story of the housing crash and its impact on communities of color proves historically complex.

The Mythical Neutral Housing Market

Historians of urban and suburban America have long pointed out the fictitiousness of free markets in housing. Federal and state interventions, whether it be investment due to wartime mobilization, the codification of racialized housing policies through the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), or the injection of federal money into suburban homeownership from the G.I. Bill and its home loan provisions, have shaped housing markets. “We guide markets to produce the results we want,” Hernandez points out. Market interventions by the state — be it mortgage loan structure, G.I. benefits, or urban planning — have functioned to reproduce racial inequality, he argues. The fact that people of color were not only targeted for subprime loans but also disproportionately affected by the subsequent housing crisis aligns with historical precedent.

Beginning in the 1920s, the National Association of Real Estate Brokers (NAREB) established racial covenants as a requirement for new home building. When the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) and FHA came into being in the 1930s, they absorbed and institutionalized the idea that homogenous white neighborhoods represented the safest investment in housing.

Heterogeneous communities and communities of color were rated poorly or redlined, which severely constrained access to home loans thereby contributing to neighborhood decline as larger numbers of non-whites moved to cities like Sacramento, but could only access housing in redlined communities. Overcrowding in these neighborhoods placed greater stress on housing stock and local resources. The inability to secure loans for new housing or much needed renovation projects undermined housing values and established risk assessment and credit lending practices that penalized non-white homeowners.

Subsequent attempts to address declining housing stock privileged and subsidized business development and suburbanization; but came at the expense of urban minority homeowners who due to segregation could not access housing opportunity that defined post-World War II white-America. While the 1968 fair housing act attempted to remedy this structural discrepancy, it had its largest effect on then more stagnant southern metropolitan areas like Atlanta, Dallas and Houston where suburban home building occurred after rather than before the law’s passage.

Moreover, market-based attempts to provide newly built affordable housing rested on this racially and class-based home financing infrastructure such that rising numbers of non-white homeowners remained subject to established structural inequalities. Government expansion outside of housing, at both the federal and state level, further contributed to the growing diversity of California cities like Sacramento. The Korean and Vietnam Wars brought civilian and military workers to the area, roughly 25,000 with African American employees making up 10 percent of this new labor force. From 1942 to 1964, the Bracero program drew greater numbers of Mexican labors to the city as well. For example, after a stint working in Salinas for a sugar manufacturer, Hernandez’s father came to Sacramento in the late 1940s where he met his future wife who then worked as a waitress in downtown Sacramento. In the postwar periods, Sacramento dinners and restaurants like the one at which Hernandez’s mother worked, later enjoyed a growing clientele due to the growth of state government. When California’s administration expanded, strict fair employment practices resulted in greater numbers of non-whites coming to the capital for work in state government.

The new arrivals, driven by government intervention in labor markets, could only find residence in neighborhoods redlined by state and private housing practices — Even military service failed to break lines of segregation as non-white military service members could only settle into low-income largely non-white communities. Adding to this demographic crunch was the city’s policy of urban renewal, which evicted thousands of non-white residents from neighborhoods like the West End in the name of economic development and highway construction, funneling them into previously redlined communities such as Oak Park.

Attempts at Reform

During the 1960s and 1970s, the FHA made efforts to reach minority homeowners. Congress passed the 1968 Fair Housing Act and the 1977 Community Reinvestment Act (CRA); the latter required banks receiving Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) funding to undergo reviews to determine if they offered sufficient levels of credit in communities in which they operated.

Each had flaws. Though the 1968 Fair Housing Act attempted to ensure equal housing, it lacked any real mechanisms for enforcement. “Anti-discrimination laws appearing in the 1960s,” notes Hernandez, “provided no basis for attacking mortgage redlining.” The CRA did threaten “sanctions against lenders who failed to underwrite loans for qualified buyers in previously underserved areas,” but as critics have pointed out, gave too much leeway to banks. No formal criteria for evaluating this mortgaging lending in minority communities emerged and capital flows to suburban areas still largely open to only whites persisted. Even worse, these reforms coincided with the economic troubles of the 1970s and the deregulation of banks in the 1980s.

Deregulation and the Rise of Subprime Loans

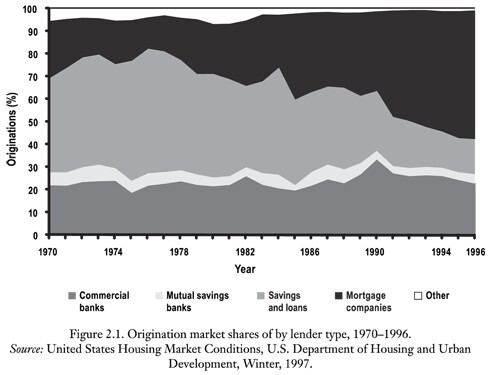

During the 1980s, local thrifts, sometimes referred to as savings and loan associations, collapsed or merged with larger financial institutions. Thrifts had once been the source of a significant proportion of the home mortgage market, however, reduced government oversight and mergers led to the dominance of larger regional and national banks. These banking institutions turned to securities markets for home loans in a process that is known as securitization, whereby high-risk loans are bundled into pools that could be sold on Wall Street as securities.

Historically, the mortgage market had been reliable and long term, producing low profits based on fixed rate steady mortgages. In contrast, securitization promised greater rewards to investors via fees, adjustable interest rates, and sales. By selling off mortgages to Wall Street investors, lenders were no longer responsible for losses on mortgages in redlined communities, but it did expand risk more broadly across economic sectors. Hence when the housing crash came in 2008, the risk had not been compartmentalized but rather spread further across the national economy.

In retrospect, it is easy to see that subprime loans reflected a larger shift in credit flows. Check cashing and finance companies also proliferated in the 1990s and many large banks invested in them. Through what Hernandez and others refer to as “fringe banks”, financial institutions delivered “hybrid credit delivery chains” to both borrowers and Wall Street investors, but this came with greater financial risk.

By the mid-1990s, subprime loans had become the most prominent of predatory credit lines. Between 1992 and 1999, subprime loans in the U.S. grew by 900 percent with most sold in minority communities and, in some instances, to “cash poor, house rich” homeowners. For the years 2005 and 2006, the volume of subprime loans exceeded $600 billion annually. One national study reported that blacks were two times more likely than whites to receive subprime loans; Latinos nearly the same. In Sacramento, subprime loans predominated in nonwhite communities, most of which had experienced redlining and been denied access to credit in the 1960s and 1970s.

Banks could ignore risk since credit rating agencies provided evaluations that downplayed the precarious financial nature of this new system. Credit default swaps, which essentially amounts to insurance on a loan, issued by Wall Street firms on securities containing subprime loans insured those holding the securities, but also encouraged rampant speculation. Banks began to focus far less on a borrower’s ability to repay loans. According to one study, in 2006, 40 percent of loan approvals had failed to consider the borrower’s income.

During the 1970s, the integrated communities to the north and south of Sacramento’s Central Business District (CBD) struggled with the persistence of redlining policies. As a result, these neighborhoods remained economically unstable. Homeowners in these areas endured much higher rates of denials for traditional loans than communities to the east and west of the CBD that had been walled off historically by housing covenants. Homeowners denied loans were five times more likely to pursue a subprime loan. At the height of subprime activity in Sacramento around 2005, 44 and 41 percent of loans sold in the area were subprime loans to blacks and Latinos respectively, nearly double the total of subprime loans to other racial groups.

By 2000, the Sacramento housing market had begun to accelerate as San Francisco Bay area residents moved to the state capital for more affordable housing. FHA loans could not keep up with the overheated market as home prices ballooned even in neighborhoods with non-white residents. Meanwhile, the city’s black and Latino residents turned to subprime loans, coupled with the fact that banks were incentivized to provide them such predatory loans, created the perfect storm.

Mortgage companies employed brokers who circulated in these communities and had direct personal connections with residents, which reduced “fixed costs investment for lenders-bundlers trying to reach loan applicants.” Brokers received higher fees for subprime loans. Thus, they sought out borrowers even if they qualified for conventional financing. One survey for 2005 and 2006 reported that 55 and 61 percent of subprime borrowers respectively had credit scores adequate for conventional loans. Decades of discriminatory policies that excluded many prospective homebuyers from the market left an informational deficit, which the real estate industry exploited. As a former real estate industry professional, Hernandez witnessed first hand the various ways brokers and lenders obscured the more dangerous aspects of subprime loans.

Navigating brokers, lenders, title companies and other aspects of the industry is complicated for even the most experienced buyer. It requires professional knowledge, or at the very least competent assistance; the latter was not provided to black and brown homeowners, Hernandez argued. Add to that the financial benefits and the place of homeownership in the American ideal, particularly for communities long denied access and you have a dangerous combination. Brokers saw better returns on subprime loans, banks packaged them for lucrative securities on Wall Street, and the housing market, everyone believed at the time, could go nowhere but up, so why not push subprime borrowing?

Unfortunately, when housing collapsed, working-class homeowners, particularly those in formerly redlined communities, got hit the worst. “Subprime lending exploited spatial racial disparities built up during decades of racial redlining and discrimination in credit markets, as well as by banks’ withdrawal form minorities neighborhoods,” argued a 2013 study.

In 2014, University of California Haas Institute for Fair and Inclusive Housing reported that of the 100 cities with the highest rates of “underwater mortgages,” 71 were metropolitan areas in which blacks and Latinos made up 40 percent of the population. The list contained 18 California cities, Sacramento among them. A new foreclosure to rental industry, in which large corporations scooped up foreclosed homes on the cheap and then turned them into rentals, arose to capitalize on the dregs of housing defaults. Take, for example, Colony Capital, which began buying up foreclosed homes in the Bay Area and Sacramento. Due to the uneven effects of the crisis on black and brown homeowners, this often happened in communities long affected by discriminatory housing policy. By 2013, Colony Capital owned 142 homes in the Oakland-Fremont metropolitan area and 114 in Sacramento. In rising housing markets, this also drove up rents, according to Oakland’s Department of Housing and Community Development, rents increased by 15 percent in 2013. Sacramento has experienced similar dynamics. “How many different ways can we reproduce the rental wealth gap?”, Hernandez asked facetiously.

Late in 2016, the National Fair Housing Alliance, representing a coalition of fair housing groups, filed a federal lawsuit against Fannie Mae and other large mortgage companies, arguing that when the crash came foreclosed homes in middle and working-class white communities received more care than those in black and brown neighborhoods. Evidence marshaled by the NFHA, the New York Times noted in an editorial, suggests “standards are being applied unequally.”

How complicit or responsible companies like Fannie Mae were for the devastating impact that the housing crisis delivered to minority communities will be determined by the courts. But the lawsuit harkens back to the very issues that drove redlining and its effect on urban America. The struggles of Sacramento’s minority communities and others like them across the nation after the crash have direct connection to decades of policies before the emergence of subprime financing. Markets and policies cannot be neutral when they are built on a racialized foundation.

Top Image: A foreclosure sign in Salton City, CA. 2008. | Jeroen Elfferich/Flickr/Creative Commons

If you liked this article, sign up to be informed of further City Rising content, which examines issues of gentrification and displacement across California.

Sources

Jesus Hernandez, “Redlining Revisited: Mortgage Lending Patterns in Sacramento, 1930 – 2004”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 33.2 (June 2009).

Jesus Hernandez, Interview with author, April 28, 2017.

Jesus Hernandez, “Race, Market Constraints, and the Housing Crisis: A Problem of Embeddedness”, Kalfou Vol. 1 Issue 2. (Fall 2014).

Dymksi, Hernandez, and Mohanty, “Race, Gender, Power and the U.S. Subprime Mortgage and Foreclosure Crisis.”

Gary Dymksi, Jesus Hernandez, and Lisa Mohanty, “Race, Gender, Power and the U.S. Subprime Mortgage and Foreclosure Crisis: A Meso Analysis”, Feminist Economics, 2013.

Darwin Bond Graham, “The Rise of the New Land Lords”, East Bay Express, February 12, 2014.

Christi Baker, Kevin Stein, and Mike Eiseman, "Foreclosure Trends in Sacramento and Recommended Policy Options: A Report for the Sacramento Housing and Redevelopment Agency", The California Reinvestment Coalition (April 2008).

Dan Immergluck, "Foreclosed : High-Risk Lending, Deregulation, and the Undermining of America's Mortgage Market", Cornell University Press (April 2016).

Alex Schwartz, Gregory Squires, Peter Dreier, Rob Call, and Saqib Bhatti, "Underwater America: How the So-called Housing "Recovery" Is Bypassing Many American Communities", Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society (May 2014).