From Slavery to Social Contract: An Economy Designed to Leave Out Many Workers

This article is part 2 of a 4-part essay about the informal economy by Pascale Joassart, co-producer of "City Rising: The Informal Economy." Read Part 1, Part 3 and Part 4.

History of Labor Market Segmentation: From Slavery to the Social Contract

More About the Informal Economy

To understand the prevalence of informality in our contemporary economy, we need to step back in history and see how labor markets have always worked in ways that purposely divided workers, keeping some people out, preventing them from enjoying the benefits of a growing economy, and ensuring that we would always have a large supply of cheap labor.

In pre-capitalist society, the economy was predominantly agricultural. Free people typically worked independently as farmers and craftsmen. Wage labor was extremely rare and to the extent that there were no labor laws in place, formal and informal labor were indistinguishable. From the beginning of our nation’s history, however, a variety of laws, institutions, and social norms have contributed to the creation of a segmented or dual economy. Many people were left out by design: slaves are the most obvious example; Native People and Mexicans who lost their land and most of their rights; women who were not allowed to vote, own property, or start a business; and immigrants who were asked to go back home. Everywhere they looked for work, these groups faced barriers of entry to the formal economy and had to find ways to make a living in a parallel economy. To put it simply, our economy was organized around laws that were designed by and for white men, particularly property owners, who used the legislative process to maintain and strengthen their position of power in American society.

To put it simply, our economy was organized around laws that were designed by and for white men, particularly property owners, who used the legislative process to maintain and strengthen their position of power in American society.

As we began industrializing, wage labor became the norm. New factories needed labor and workers moved to cities to join the industrial labor force, including a rising number of immigrants from Europe, women, and recently freed slaves. But working conditions were extremely harsh and discrimination rampant. People who could not access factory jobs – women, children, immigrants, blacks– made a living as street vendors, domestic workers, etc. Cities became overcrowded and lacked the proper housing and infrastructure to accommodate the growing population. Many were extremely poor and lived in tenements and boarding houses. By today’s standards, these factory jobs would be considered informal since there were no worker protections in place, as in contemporary sweatshops. However, since there were very few applicable regulations, these work arrangements were perfectly legal.

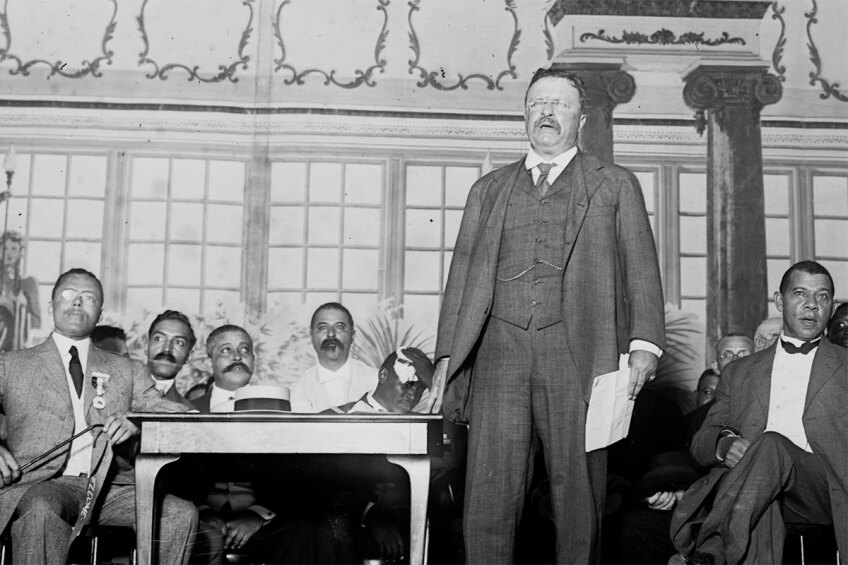

This post-civil war era of rapid industrialization is also known as the “Gilded Age” – a period of huge inequality, shady business practices, robber barons, and political corruption hidden under the spectacle of industrialization. In the late 1800s, in the midst of poverty and inequality, a progressive movement emerged in a few large cities like New York and Chicago, creating charitable organizations and calling upon the state to take a more active role in protecting workers and ending corruption. This signaled the beginning of the “Progressive Era” during which protections for workers and consumers were strengthened, unions became more active, and women finally achieved the right to vote. During that time, there was a generally optimistic assumption that capitalism was a powerful economic machine that would progressively improve everybody’s standard of living and therefore remove any pre-capitalist and informal forms of work.

Even during this progressive period, however, people of color were often left out. In fact, conservatives, including corporate leaders, fought hard against progressive reforms and pressures to allow unionization and improve the standing of women, blacks and immigrants. Many, particularly in the South, supported very racist ideologies and argued to keep the role of the federal government to a minimum.

The Great Depression of 1929 – a direct result of growing inequality and speculation – was too big for the government to ignore. The debate shifted from whether the government should intervene in the economy to how it should do so. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “New Deal” helped address some of the direct consequences of the crisis with relief programs for the unemployed and job creation through federal spending. It also included long-term reforms through regulatory legislation and the creation of new social welfare programs. The National Recovery Act, for instance, sought to boost businesses’ profits and workers’ wages by establishing industry-by-industry codes that set prices and wages, as well as guaranteeing workers the right to organize into unions. Other important legislations included the Social Security Act and the Fair Labor Standards Act. These provide the first comprehensive set of social and legal protections for workers. These laws, along with the massive military expenditures of World War II, eventually pulled the United States out of the Great Depression.

As the economy recovered and began to grow rapidly, the social contract laid out by the New Deal was solidified and we entered a period of shared prosperity anchored in Keynesian economics—the theory that government spending can stimulate the economy by putting money in the hands of workers and consumers who then support private businesses through consumption and encourage growth and job creation. Wages and productivity were rising, as were tax revenues and profits, supporting a growing economy in which the state played a central role. The government expended public infrastructure, supported education, and put in place a new regulation to increase workers’ protections and benefits.

Yet, as with previous progressive reforms, some were excluded from these benefits. For instance, there were different labor standards in place for agricultural workers – mostly immigrants and Blacks. Jim Crow laws still prevailed in the South, keeping African Americans in deep poverty and forcing many to work informally as domestic workers, janitors, and farm laborers. Even after the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, African American experienced little improvement in their everyday work experience. The racial uprisings of the 1960s and early 1970s in Detroit, Cincinnati, Los Angeles and many other US cities were responses to the continued discrimination blacks faced, including poor housing conditions, police brutality, and sub-standard schools. These tensions led to massive white flight away from central cities. As more affluent residents and businesses relocated to suburbs, cities hollowed out and became places of concentrated poverty with very few employment opportunities. People who were socially and spatially left out from the expanding economy turned to informal jobs – and in some cases illegal activities. In Black ghettos and ethnic enclaves, informal work became a survival strategy. This was how people obtained food, housing, and most of their basic needs since the formal economy had abandoned these areas.

Progress for women was slow too. While many joined the labor force during World War II, in the post-war period, they found that doors were often closed, keeping them in low paying and gendered occupations such as health care, domestic work, and supportive business services with limited upward mobility. Persistent social norms regarding women’s responsibility for child rearing and domestic tasks, along with a lack of publicly funded child care programs, also prevented many women from entering full time employment with rigid schedules. Many, especially those who could not afford the high cost of child care, turned to the informal economy as a way to earn an income. Because this type of work is often perceived as a continuation of their domestic responsibilities, such as cooking, cleaning, caring for children or elderly and other tasks believed to come “naturally” to women, it has typically been devalued and underpaid.

In short, despite great progress, race and gender discrimination helped reproduce a dual or segmented labor market where minorities, women, and immigrants have been pushed into a parallel segment, working alongside formal workers for lower wages and with fewer benefits and protections. This is not an accident; it was the result of policy choices that ensured the continued availability of a large pool of workers willing to work for low-wages and less likely to organize. Having this sort of reserve army of labor has been central to the success of capitalism.