The Forgotten Fight for Civil Rights at San Francisco's Sutro Baths

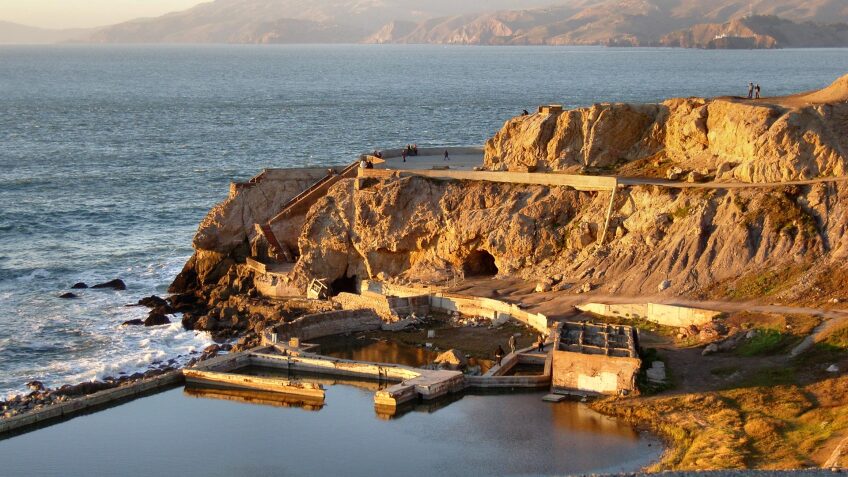

In San Francisco, along the coast are the remnants of Sutro Baths. Since 1973, this has been a part of Golden Gate National Recreation Area, but many years prior to that, it stood as a testament to the Gilded Age, a magnificent complex that harbored an injustice hidden within this lavish gift to the people of San Francisco.

Sutro Baths was both a public recreation center and a monument to the wealth of Adolph Sutro built near the end of the engineer's life. Sutro was an immigrant from Prussia who quickly made his way out to California around the time of the Gold Rush. He made a name for himself, though, in Nevada, where he built the Sutro Tunnel that helped miners access silver ore. Ultimately, though, he returned to San Francisco. Here, he accumulated loads of land and, ultimately, became mayor of the city for a two-year stint. According to the Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco, Sutro's mayoral platform was a populist one. That populist bent ties into his next endeavor, the Sutro Baths.

The Baths were designed to be an ocean-adjacent swimming complex that people could afford to use. The U.S. National Park Servicenotes that there were seven pools and, overall, Sutro Baths had a capacity of 10,000. Moreover, they provided bathing suit and towel rentals. The facilities also included museum-type exhibits of art and artifacts, including Egyptian mummies, and hosted events like concerts. It was a recreation complex for everyone. Or, rather, it was a recreation complex for everyone who was white.

On August 1, 1897, San Francisco Chronicle reported that a man named John Harris had filed suit the previous day against Adolph Sutro. The reason: Harris alleged that he had gone to the Baths on the Fourth of July and was able to buy a ticket to enter the facilities. When he went to rent a bathing suit, though, he was denied on the basis of his race. In fact, Harris tried to visit the Baths twice. On his return trip that month, he was again denied use of the pools.

The following day, the San Francisco Call ran a story titled, "Negroes Claim Civil Rights: They insist upon equal privileges in public baths," noting that the suit was for $10,000 in damages. The story also noted that the superintendent of the Baths said non-white people were allowed to go to complex, but not were permitted to go into the water. He argued that this was a business decision based on their belief that white people would not patronize an integrated pool. Furthermore, Edgar Sutro, Adolph's son, argued the same and added that there weren't enough people to support segregated pools. The two were certain that they would win the case.

They didn't. On February 17, 1898, Sacramento Daily Union reported that John Harris was awarded $100 in damages. That was a much smaller sum of money than the original suit requested, but the point was made. Those pools were for everybody.

Sutro Baths opened a year before Harris filed suit, but the National Park Service notes that this was also the year that Pleassy v. Ferguson-- the "separate but equal" case-- hit the Supreme Court. Segregation had been upheld on a national level, but, in California, things were changing. NPS also points out that, in the years prior to the opening of the Sutro Baths, various anti-discrimination laws had been passed. The one most relevant to Harris' case was called the Dibble Act.

According to an article inSF Gate about Harris' case against Sutro Baths, the Dibble Civil Rights Act was named for Henry Clay Dibble, a former Union soldier who fought to end discrimination in the post-Civil War South before heading to California, where he served in the State Assembly. The law named for Dibble said that people were not to be denied access to public places because of their race. It went into effect a few months before Harris' exclusion from Sutro Baths.

The story from the San Francisco Call reported that a group called The Assembly Fund was prepared to help finance Harris' case and this was a way of testing out the newly enacted Dibble Civil Rights Act. In fact, it turned out to be a pretty good test of the law. National Park Service indicated that the jury for this case asked to ignore the new law, which may have been missing the point. The SF Gate story notes that the lawsuit against Sutro Baths led to similar cases across California.

While this seems like the sort of story that would have been big news at the time, this may not be the case. Looking through newspaper archives, stories about Harris' case are buried within lots of other news related to the Baths, some stories about events, other delving into legal issues related to Sutro's failing health and his assets. In fact, Adolph Sutro died in August of 1898, about a year after Harris filed suit.

Sutro Baths lived on for a few more decades. According to the National Park Service, the complex's popularity waned in the 1930s with the establishment of new health codes and the Depression leading to less access to transportation. At one point, the Baths became an ice skating rink, but this transition didn't bring in anticipated crowds. By the mid-1960s, the property had ended up in the hands of developers with the intent of building housing, but after a fire in 1966, those plans were quashed too. Today, it's a tourist site for people fascinated by the remnants of what once stood there, but even now, this place's significance to California's civil rights history is obscure. A 2011 story that originally appeared in the Ocean Beach Bulletin credits historian John Martini, a former park ranger who gave tours in the area, with unearthing the information about John Harris' case against the Sutro Baths. In this interview, Martini said that he suspected that there could have been a culture of discrimination here, but didn't know for sure until he stumbled across an old article about the case.

The SF Gate story, which ran in 2012, added that even the Dibble Civil Rights Act was a pretty obscure part of California history. This article notes that, when the Unruh Civil Rights Act was passed in 1959, it was perceived to be the first law of its kind in California, even though Dibble preceded it by more than 50 years. In fact, the Dibble Civil Rights Act and Harris' case didn't altogether end swimming pool discrimination in California. In Orange County, there was a pool built in the 1930s with separate days for white and Latino swimmers. Moreover, it wasn't until the post-World War II erathat the U.S. as a whole started seeing the desegregation of pools. Still, Harris' lawsuit against Sutro Baths was an important point in the struggle for equal access to public places.

Top Image: Ruins of the Sutro Baths/Fredhsu/CC BY-SA 3.0