California's National Parks Were First Protected by Buffalo Soldiers

Today, the National Park Service’s 362,000 volunteers and employees protect a total of 417 of the most beautiful regions throughout the country. This encompasses over 84 million acres in each state, in addition to the Virgin Islands, Guam, Puerto Rico, American Samoa and the District of Columbia.[1] In California, that includes 28 national parks, from Yosemite to Joshua Tree.[2] Despite such vast jurisdiction, it was not until 1872 that the world’s first true national park, now known as Yellowstone, was established. Furthermore, it wouldn't be until the early 20th century that a unified system to protect these sprawling landscapes from competing interest would be developed.[3]

Up until the establishment of the National Park Service in 1916, the preservation of these magnificent terrains were left to the Army and, in California, a lesser-known yet substantial group of African American soldiers. Surely, as many Americans migrated west in the latter half of the 19th century, these vast areas were threatened by the drive for development that characterizes American capitalism. While discordantly tasked with protecting American settlers as they crossed the frontier, this group of troops, known as “Buffalo Soldiers,” worked tirelessly to protect and improve national parks, leaving a significant impact on the state’s most majestic landscapes.[4]

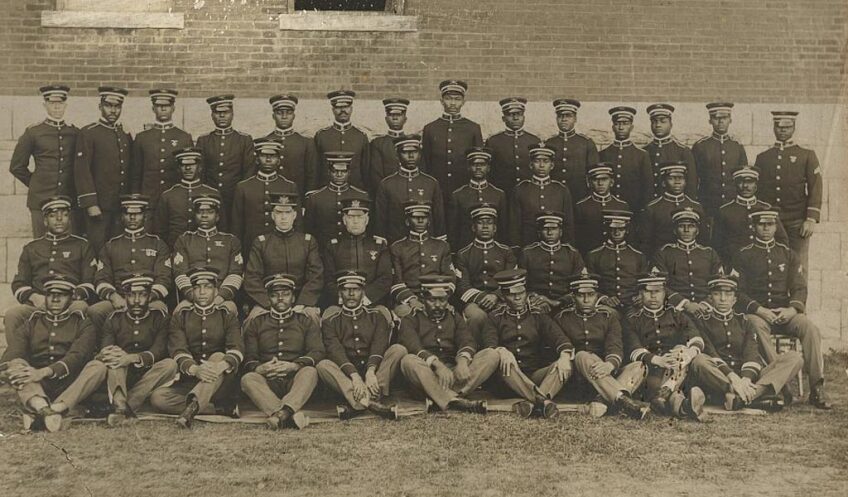

Developed in 1866, the “Buffalo Soldiers” consisted of black Civil War soldiers, former slaves and freemen.[5] Experiencing constant discrimination, many had joined the military in search of social and economic opportunity that was seemingly unobtainable in civilian life.6 According to the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy, the troops received their names from “Native Americans against whom the black soldiers fought during the so-called Indian Wars.”[7] "The Indians call the colored troops buffalo soldiers on account of their kinky hair,” an 1879 article from the Sonoma Democrat states, “They never scalp them, and dislike fighting them, because when they kill them the braves have nothing to show for their prowess.”[8]

The “Buffalo Soldiers”, with a total of 5,000 troops, consisted of four all-black U.S. army units — the 9th and 10th Calvary Regiments and the 24th and 15th Infantry Regiments — and accounted for roughly 10 percent of U.S. soldiers stationed on the Western Frontier.[9] Not always welcome in certain towns due to the color of their skin, these men served roughly 30 years at the nation’s most desolate and harsh posts, surviving on cast-off supplies from white troops. Despite such harsh circumstances, the soldiers, according to the National Park Service, relentlessly “garrisoned forts, protected settlers and railroad crews, guarded mail and stage routes, built roads and forts, strung telegraph lines, and generally kept the peace."[10]

In addition to these duties, two of the units, who were garrisoned in California at the Presidio in San Francisco, took on a distinguished assignment. Called upon to oversee Sequoia, Yosemite and Kings Canyon National Park, the 24th Infantry actively patrolled the areas in 1899 followed by the 9th Cavalry from 1903 to 1904. [11] According to Ranger Frederik Penn, “it was the soldiers’ job to take care of the parks, to make sure that loggers weren't cutting down the trees, hunters were not killing off all the animals, there weren’t any forest fires.”[12] By assuming this role, black men in these regiments can be identified as some of the state’s first National Park Rangers. Furthermore, while patrolling the regions, Buffalo Soldiers of all ranks played an essential role in their preservation in the absence of an established government system.[13]

Equally important, the significant presence of the “Buffalo Soldiers” in U.S. military conflicts during Americans’ push westward proved that they were an integral part of the nation’s expansion during this period. According to the National Park Service, “It is thought that more than 12,000 served during the late 19th century,” participating in “more than 125 engagements with American Indian tribes” in addition to pursuing “Mexican outlaws and border desperadoes.[14] Due to their bravery and determination in battle, 18 troops received Congressional Medals of Honor, which the National Park Service acknowledges as proof of the “Buffalo Soldiers” more important and unwavering “legacy of courage and patriotism."[15]

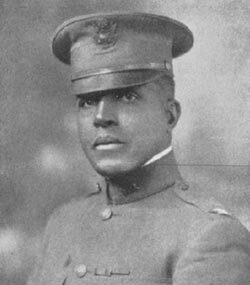

Only the third African American to graduate from the competitive U.S. Military Academy at West Point, Colonel Charles Young, Captain of the 9th Cavalry, embodies this legacy as a respected military leader. Before leaving the Presidio in 1904, the Captain and his regiment had a lasting impact on Sequoia National Park, which they had been tasked to patrol. Commanded specifically to develop a wagon road that would improve access to the park, Young and his men, unlike straggling military administrations before them, took fervently to road construction.

Within four months of the 9th Cavalry’s arrival, wagons began rolling into the Giant Forest — today one of the park’s main attractions — for the very first time.[16] In a 1904 article titled “Negro Goes to Hayti as Military Attache,” the Los Angeles Herald justifiably honored Young, claiming the Captain “possesses a fine record.” More significantly, however, after completing the same amount of road that had been built in the three summers prior, Young continues to be honored by the National Park Service:

The energy and dignity he brought to his national park assignment left a strong imprint. His roads, much improved in later times, are still in use today, having served millions of park visitors for more than eighty years. And the example he set — a determined black man overcoming the prejudices of society — remains an inspiration to anyone who faces life's challenges head-on.

Source Notes:

1. https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/faqs.htm

2. https://www.nps.gov/state/ca/index.htm

3. https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/hisnps/NPSHistory/timeline_annotated.htm

4. http://www.buffalosoldiermuseum.com/who-are-the-buffalo-soldiers/

5. Ibid

9. http://www.buffalosoldiermuseum.com/who-are-the-buffalo-soldiers/

10. https://www.nps.gov/jeff/learn/historyculture/upload/buffalo_soldiers.pdf

12. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yhq-XQfk5AY

13. Ibid.

14. https://www.nps.gov/jeff/learn/historyculture/upload/buffalo_soldiers.pdf

15. Ibid

16. https://home.nps.gov/seki/learn/historyculture/young.htm