The Empowering and the Personal in Helado Negro's 'It's My Brown Skin'

The video for Helado Negro’s “It’s My Brown Skin” is suffused with light, from the summer sun that shines down on the largely Latin American neighborhood in Brooklyn where it was filmed, to the smile on the face of a woman who stops to walk with the artist himself, real name Roberto Carlos Lange, as he strolls down the street.

At the same time, the video, directed by Spanish filmmaker Martin Allais, ventures to express no less weighty a subject than the nature of self-perception, and the space between our own self-regard and the ways in which others perceive and treat us.

“It’s My Brown Skin” is first and foremost a song about loving one’s self — as simple and personal an act as it is a transgressive one, particularly for people of color in America. “My brown skin is the color that holds me tight,” Lange sings.

“It was something I'd been thinking about, and obviously it’s something I live with a lot,” says Lange. "At the time, it was a way to talk about me being brown. It’s something that people look at and talk about and think about when they see me, and I think about it, whether or not it’s at the front of people’s minds."

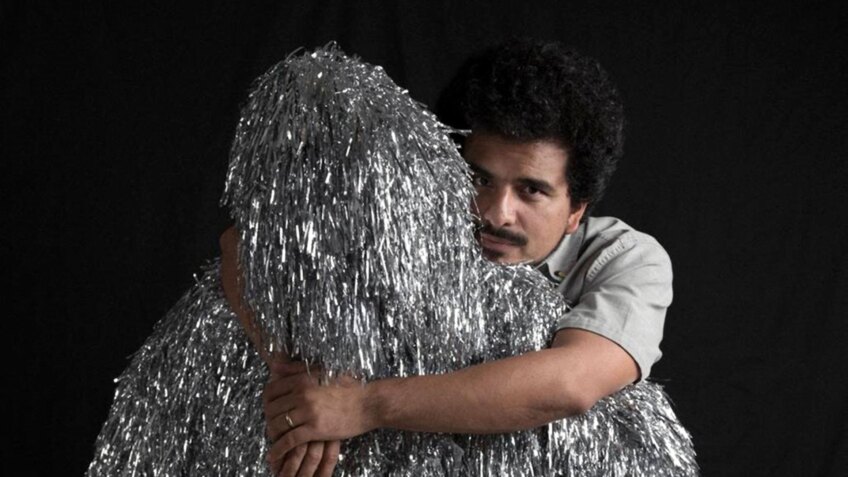

Lange’s approach — talking about his skin as if it’s a lifelong companion — opens up an deep well of perspective on color, representation, and self-regard, which are explored in Allais’ video in ways both relatively conventional and gently surreal, like the portraits of Lange and others in which sheets are draped over their faces, or parts of their body are colored over.

Allais says he wanted to riff visually on the ways in which skin color can send signals about identity while obscuring it at the same time. “The sheets were about materializing the idea of what covers you,” says Allais.

“It’s My Brown Skin” was one of the final tracks assembled for “Private Energy,” the fifth and latest full-length Helado Negro album. According to Lange, this track tied together some of the record’s overarching themes. Like previous Helado Negro releases, “Private Energy” is a complex stew, full of musical and lyrical experiments both overt, like the scrambled syntax of “Runaround," and subtle, like the distant, pillowy sample in the background of “It’s My Brown Skin” that gives it its faintly otherworldly quality.

On the whole, the album takes much the same general approach as “It’s My Brown Skin” in a process of self-reflection and discovery extending outward to a broader message of inclusivity and empowerment.

"My identity has a lot of things in common with a lot of people, but I’m not the same person as the next brown person...That’s the whole idea here, that we’re all so distinctly wonderful and unique."

“We’re all figuring things out on our own, and my identity has a lot of things in common with a lot of people, but I’m not the same person as the next brown person,” says Lange. “That’s the whole idea here, that we’re all so distinctly wonderful and unique.

“[I was] trying to make something that was not generic but sincere — not too universal but very much my feeling toward [the idea of], how can we embrace everyone?” Lange says.

Allais’ video premiered on Nov. 1, just one week before the U.S. presidential election; in the post-election landscape, when the mood suddenly seems more palpably hostile toward immigrants, and those whose ideals run counter to the president-elect’s find themselves in a more confrontational environment, the song takes on new dimensions.

They are dimensions with which Lange is still grappling. In particular, he’s reflecting on the mantra that closes the song: “It’ll keep you safe,” which he repeats over whirring synthesizers.

The line "means understanding what it means for you to feel safe in your skin, and to feel safe in your skin for me means being happy with who you are,” says Lange.

“Post-election, I had a completely different perspective on [the song], where it also forces you to feel like [your skin is] a shield, because there are a lot more confrontational situations people are feeling the need to have, to speak out about a lot of things."

“But post-election, I had a completely different perspective on it, where it also forces you to feel like [your skin is] a shield, because there are a lot more confrontational situations people are feeling the need to have, to speak out about a lot of things. And it is a shield, it’s supposed to be you, that's all it is."

Lange says he worries in this new climate about those who find themselves thus empowered, and the situations in which they may find themselves.

For instance, Lange created T-shirts printed with the title of another of “Private Energy”’s songs, “Young, Latin and Proud,” that turned out to be popular with his fans.

“I get messages from people who are saying, I’ve always wanted to dive into my heritage, and I’ve just never felt comfortable, and I’ve been feeling it more these past couple of years and [“Young, Latin and Proud”] has done a lot for me in that respect,’” Lange says.

“And I’m not really doing them justice in terms of what they wrote, but I’m also thinking, you’re wearing this shirt that says this thing that’s confusing for some people, you know?” he continues. “I want people to have this sense of pride and not be afraid to feel that. But it’s also like, I don’t know what the cost is for them."

That is a sentiment that seems to come purely from Lange’s deep empathy for his listeners — and it is in fact this empathy, radiating from an astute reckoning of self, that makes “Private Energy,” and “My Brown Skin” in particular, such a captivating work. Allais’ video, with its balance of the warm and surreal, only serves to underscore how that empathy can lead us to new ways of looking at ourselves.

In that sense, one of the most powerful moments of the video is when Lange spontaneously puts his arm around a woman who happens to be walking down the sidewalk during the shoot. Meanwhile, he is singing, to the skin that is his shield, the sheet that covers him: “Because I love you/And I can’t miss anything but you/And you’re stuck on me/And all this time I’m inside you.” Both acts — the act of reaching out to a stranger, the act of singing a loving ode to one’s own skin — feel immensely powerful in that moment, in which radical self-love meets a radical love for others.