Letter to My Father Concerning the State of the World

Relive the excitement of man’s first steps on the moon and the long journey it took to get there with 20 new hours of out of this world programming on PBS SoCal’s “Summer of Space" Watch out for “American Experience: Chasing the Moon” and "Blue Sky Metropolis," four one-hour episodes that examine Southern California’s role in the history of aviation and aerospace.

I am never sure what to call you. You died over 50 years ago, when I was two years old. I imagine I had a syllable for you then, something I chattered when I saw your face or when my mother said, “Daddy, Daddy is coming.” You died when you were thirty-two years old. I could be your mother now, but using your given name Mel or Milburn hardly feels right. In that mythic country where parents live large as gods, you are still a father, not a son. Instead I use the word Dad, hesitantly, having never actually said this to a living person.

You died testing the X-2, an experimental rocket research plane that screamed along at 35 miles a second and then fell 65,000 feet. The newspapers called you the fastest man on earth. You set your speed record and turned back to the dry-lake landing strip at Edwards Air Force Base in the middle of the Mojave Desert. Suddenly the plane dipped and rolled. You were knocked unconscious. The X-2 went into an inverted spin. You woke and tried to regain control. Finally you jettisoned the cone of the plane, which also served as an escape capsule. The capsule pitched forward and you were battered again into unconsciousness. Again you woke (all of this recorded by the cockpit’s camera) and tried but failed to release your parachute.

No one wanted this to happen. But no one could have been surprised, either. In the 1950s, pilots died all the time. A Navy pilot who flew for twenty years had a 23 percent chance he would die flying — and this did not include combat. At Edwards Air Force Base, 62 fighter pilots died during one 36-week training course. Statistically, a test pilot died every week of the year as he climbed into unproven and unpredictable machines that had aerodynamic quirks such as control reversal or somersaults. Sometimes the instruments lagged behind the plane’s actual performance. Sometimes the plane’s rockets stopped with a semi-explosion or tail fire. Sometimes the plane went higher than anyone had ever gone before, or faster, or longer. Sometimes you were the first human being ever to do this particular thing, something few people will ever know, a feeling that must have been godlike, exhilarating, like you were flying into the future as you fulfilled the destiny of our species, defying natural law.

See the birth of the aviation and aerospace industry in Southern California on the four-part documentary series "Blue Sky Metropolis." Watch a preview.

Ad Explorata was the motto of Edwards Air Force Base. Toward the unknown. With its cutting-edge wing shape and heat-resistant body, the X-2 was that unknown, a beautiful mystery. Its own designers were not sure what it could do in the air. Initially they had two X-2s, but one model inexplicably exploded while about to be launched from the belly of a B-50, killing two men. The pilot in the chase plane that accompanied you the day you died had already flown the X-2 higher than 120,000 feet where in essence he was in space, above the curvature of the Earth in a blue-black sky. At that point, the controls went “mushy.”

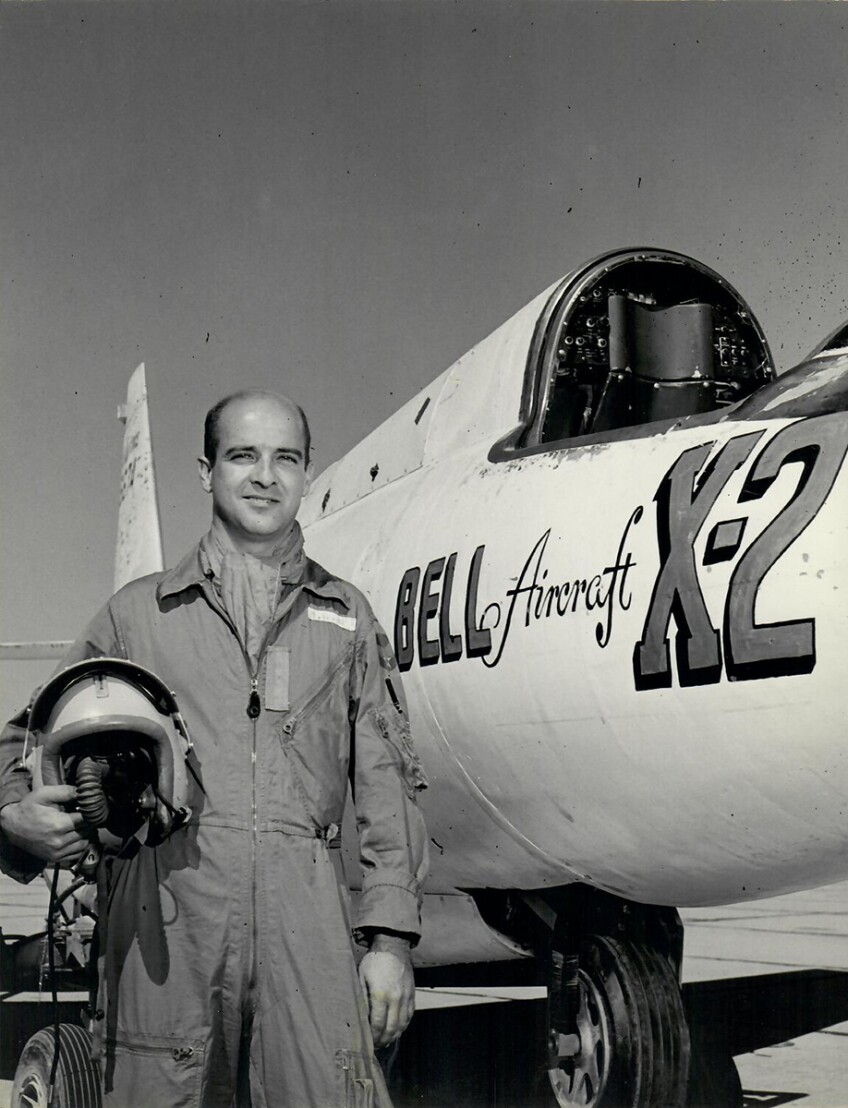

Of course, you begged for the chance to fly this plane. By 1956 you had spent over 3,000 hours in the air and flown all the tricky, experimental Century Series jet fighters. You helped debug the F-100 by, as one observer wrote, “inching steadily closer to the speed at which the plane went crazy.” You brought the multi-million-dollar F-105 back to base with an engine fire rather than abandon it. One test pilot put your skills in practical terms, “All the manufacturers used to ask for the guy with the bald head.” That was you, prematurely balding, short and slight, with a seemingly shy smile.

Once, when you were flying chase for a plane being tested, that plane also crashed in the Mojave Desert. You landed and rushed over to help. “It was nothing but fire,” you would later tell a reporter from LIFE magazine. “The only part I could see sticking out of the flames was the tip of the tail.” On the dry lake bed that served as a runway, there were no sticks or stones to break open the Plexiglass canopy and so you beat on it with your fists, despite the danger of the plane exploding. Finally you were able to pull the pilot to safety. He lost both feet. You got a medal.

A few months later, you got the job of taking the X-2 to Mach 3, three times the speed of sound. “Here’s to the next lucky son of a gun they let ride the X-2,” went a party toast at one of the base’s many parties. On the day of your flight, as the chase pilot helped you into your pressure suit, he joked about locking you away so that he could fly the X-2 instead. (He would later die testing a Lockheed Starfighter.) Undoubtedly, you kidded back. You were, my mother once told me, the kind of fun-loving guy who wore a lampshade on his head after a few martinis. As a soldier in the Air Force, your nickname was Happy. Growing up on the family farm in Kansas, you had been a mischievous kid, full of pranks. You had an easy-going personality. You hunted a lot and fished with my grandfather. That’s about all anyone ever said — what is contained in this paragraph. After your death, no one really wanted to talk about you much, or maybe they didn’t want to talk to me. I think the pain was raw for many years.

Mostly I learned about you through reading the clippings and articles collected in scrapbooks and kept by my grandmother — from when you were in 4H, from when you were in the war, from when you saved the pilot with burning feet. The stories of your final crash froze your life into clichéd and journalistic language. You became “a member of an elite fraternity whose trademark is courage,” a man “whose job is to roll back the frontiers of knowledge,” “a cool head,” “an ace,” and “a doomed pilot on his last ride.” One account was particularly hardboiled. That author described you as a “quiet man, of medium build, with very intense eyes.” He imagined your last moments, “the brutal supersonic tumble” and “frantic last-second fight for life.” All you needed, the journalist claimed, was five seconds to stand up and pull the rip cord. “They were not given. The sand was coming up at him like a blazing yellow wall. Still in his seat, still conscious, Captain Milburn Apt struck the desert.”

I believed every word. I formed you out of need and desire from the pages of Reader’s Digest and Aviation News. In this way, I learned early the importance of story and the power of writing. You were everything I was not. You were an ace with a perfect Midwestern childhood. You were at home wherever you went. You loved your parents. You loved hunting and fishing. You may not, completely, have loved life on the farm, for at the age of seventeen you joined the Air Force and by nineteen you had your silver wings and a commission as a second lieutenant, the youngest officer from Wilson County, Kansas. You got a degree in aeronautical engineering. You became a fighter pilot in World War II. You married my mother and within six months she was pregnant.

Like almost all test pilots, you were an optimist. Other test pilots died. You would not. You were a patriot. America had won and fought the Good War. We had liberated Europe. Moreover, we were magnanimous in our victory, wise as well as brave, loved around the world. Predictably, we would be rewarded for our virtue. The 1950s were a time of prosperity and expansion. Raised in the Depression, you knew very well how to be frugal. But now you had a captain’s salary and a house on the base. You took vacations. You bought a vacuum cleaner for your wife. You believed in progress. You believed in people. We were on the cusp of something great.

I wonder what you would think if you came back today. Lately, I have been seeing you dressed in your pilot uniform, climbing out of the cockpit, holding a space helmet in one hand with its dangling oxygen tube. You have that smile on your face, the shy one you put on for the publicity photos taken by Bell Aircraft, you in front of your various planes. It is 2008 and you have been gone a long time. You missed the last half of the twentieth century. You are eager to learn what we have done with all our can-do spirit, our cleverness, our wealth. I see you looking around for me and my sister, for your wife. But also for the state of the world. By gosh, over 50 years! Into the unknown. What wonderful things have we accomplished in the name of freedom? What wonderful future do we have before us? What new dreams?

The hero. That’s the old story, the story I carried for some 50 years. It served me well. As a child, I dramatized your absence. I felt grieved and lonely and special. When President Kennedy was assassinated, when even our fourth-grade teacher cried openly in front of her class, I cried, too, more than the other children. I was privileged by my fatherlessness. I had an entrance into something big, a little scary — a little too big. Still it was something rather than nothing. Your absence became a presence.

And, of course, you always loved me. You were never disappointed in me. You never bullied or ignored me. You never thought, “Why isn’t she a boy?” You were never unjust, never merely human. I gave the hero life, and the hero gave me his complete attention as I grew up and marched — that march of progress — into my own future.

It was the 1960s, a time of social reform, civil rights, women’s rights, protests against the war, the environmental movement. By now the test pilot program had evolved naturally into the space program, with Edwards Air Force Base offering the country’s first formal astronaut training. In my family’s mythology, you would have been drawn to that challenge. You would have applied for that training. Like Neil Armstrong — the man who tested the X-15, the next major development after the X-2 — eventually you might have walked on the moon.

Conquering space was our next great achievement. We wanted to beat the Russians. We wanted another victory. But as pictures of the Earth seen from outside the Earth began to enter our cultural consciousness, something a little surprising happened. As one astronaut said, “That beautiful, warm, living object looked so fragile, so delicate, that if you touched it with a finger it would crumble and fall apart.” Another spaceman wrote, “A Chinese tale tells of some men sent to harm a young girl who, upon seeing her beauty, become her protectors rather than her violators. That’s how I felt seeing the Earth for the first time. I could not help but love and cherish her.” Some of our divisions fell away. We were bound together on one planet, one blue ball that suddenly seemed so fragile and so beautiful.

Working for NASA in the 1960s, the English scientist James Lovelock had the job of comparing the atmospheres of Earth, Mars and Venus. One day he realized that life on Earth — the totality of living organisms — had created a favorable atmosphere for itself which it continues to maintain at a favorable global temperature. Complex feedback loops include the work of tiny marine algae, weathering rock, clouds, volcanoes and trees. Although these systems of self-regulation are not purposeful or sentient, they mimic the coherency of a living being. Lovelock called this web of relationship Gaia, also the name of a Greek goddess. The metaphor still works. We live on the body of Gaia. The Earth we live on is alive and responsive, a kind of goddess.

My college years were spent reading people like James Lovelock, as well as other environmental activists. I got a B.S. in conservation and natural resources and then a Master of Fine Arts in creative writing. In the early 1980s, my husband and I moved to rural New Mexico as back-to-the-landers, where we had a house made of mud, an oppressively large garden, too many goats, too much goat cheese and two home births. We read eagerly now about composting toilets and killing gophers and pruning fruit trees. We wanted to root into the ground, root into place. In doing so, we thought we were on the cutting edge. This is what our culture, our species, also needed to do.

Our naiveté that we could live simply and sustain ourselves on this land lasted about two weeks — or perhaps a little longer. Eventually I began to teach at the local university. My husband worked for The Nature Conservancy. Our children went to public school. I was elected to the local school board. Like most people over a long period of time, we ended up being carried — as though on a river, the movement of water so sure it seemed we were standing on solid ground—by forces larger than ourselves. Slowly, over the next two decades, our lives became more middle-class. Like you — a captain’s salary! — we bought appliances that became necessities. Old home movies taken before your death and stored in trunks were first turned into video cassettes that I watched, distracted, while keeping the peace between my son and daughter. Later, with the house quiet and the son and daughter in college, the cassettes became CDs that my older sister sent me just a few months ago. Some of these films I have seen before, and some I never remember seeing.

Certainly I don’t remember the wedding, a casual affair, friends and relatives throwing rice. You walk with that fast gait we see in old movies, the camera also jerking fast, here, there, past too many faces. You stand next to my mother, and the camera jerks away again, leaving me a little surprised. I always knew you were short, “medium-build, with very intense eyes.” But my mother is 5’3” and you don’t look much taller. Perhaps she is wearing heels. Also, pilots had to be short then, small enough to fit into the cockpit, something like jockeys.

I see you holding my sister in a swimming pool. She is three years old, and you float her in a slow circle. She giggles and moves into your chest, wrapping an arm around your neck. I immediately think: you love her more than you love me. Of course you do. You had five years with my sister, who is adorable. I am not even born yet or hardly born.

I see you sitting in a lawn chair. You squint into the sun, looking grim. You are bald and thin and pale and hairy. As you bounce my sister on your stomach, you might be thinking of something else, for you seem preoccupied. Adult business. Then you smile obediently for the camera. You are … so alive.

Now, over 50 years after your death, I feel angry. You had a wife and two little girls. You had responsibilities. You begged to go up in the air and fly glamorous, expensive machines that sometimes exploded and sometimes fell down. Why? Because you could? Because you were good at it? Because it made you feel important? So that we could have better machines that go faster and higher?

In over an hour of jerky home movies, there are too many scenes of my sister opening presents at Christmases and birthdays, and then of me opening presents at Christmases and birthdays, and far too much of what you saw on vacation (Hoover Dam, the Grand Canyon, snow, trees) and only a very few pictures of you. In each one, I think: there you are! Alive and real, short and bald, looking a little pleased or a little bored, with hairy arms, loving my sister more than me. In each one I think that I would rather have had you alive like this than dead and imaginary and heroic. I think that the hero just wasn’t enough, just wasn’t good enough.

I think how strange it is to still miss a father when you are a woman with children grown. I suppose I will miss you into my old age. I will miss you always because what and who we are never goes away.

The state of the world. The taste of ashes. The taste of bile. What we do over and over out of stupidity and greed. Every day, more bad news. The ice caps are melting, coral reefs disappearing, the oceans filling up with plastic. Our most charismatic and beloved animals — lions and tigers and bears — will be gone in the wild. The rainforests gone. The sixth mass extinction. We have transformed the planet. Progress is a joke. Your patriotism is a joke. For some time now, America has failed in every way to be wise and strong and magnanimous. The last person we can believe in is ourselves. How did we get here? You were supposed to protect us. You were supposed to keep the world whole and safe for me and my sister.

Then an extraordinary thing happened, extraordinary in itself and in the fact that I hardly noticed at the time. I became the hero. I was supposed to protect my son and my daughter. I was supposed to keep the world whole and safe for my children and their children. We failed them, you and I, each in our own way.

You are the old story. Send out the young men. See what they discover. See what they can do. We can fly, and so we have to fly. We can go high, and so we have to go higher. You were young and brave and optimistic. You took risks just because you could, because it made you feel important. There was something fundamental in your curiosity and drive. Your playfulness. Designing and flying the X-2 was as purely human as hunting mammoths and gathering around the campfire. Something as old as the Greek myths. The stories of Prometheus and Icarus. The stories in our bones.

And I am no longer angry with you. How could I stay angry with you? I forgive you for dying. I forgive you for being human after all.

As a heroic symbol, of course, you are now obsolete. We no longer feel so cocky, so positive that we are on the right track. We begin to realize, falling from the sky, that this could end badly.

We begin to realize what mastery means. While the future may well include new technology — making electricity from wind and sun, algae and pet wastes — living on Gaia is not really about going faster or higher in better and more expensive machines. We don’t need test pilots. We need mayors who promote green cities. We need organic farmers. We need pacifists. We need people who drive less. We need people changing the meta-systems of law, business and education. We need people living their lives carefully. We need a multiplicity of heroes, a web of relationships. In the face of loss and sadness, we need to master our anger and greed. We need to keep trying, rooting into this place, this America, this Earth. I need to keep trying.

In a scrapbook, I have a picture taken when you were a boy. It is 1937 and you must be about thirteen years old, standing in a double-breasted suit wrinkled and tight at the chest, wearing a dark fedora hat that is too big. Your arms are stiff, your back straight. Your shy grin is lopsided and knowing. You know this is a silly picture. You are doing this for someone you love, most likely my grandmother. You are standing here, fresh and young, for love. Your eyes look right into the camera.

Underneath the photo, my grandmother has written, “Back in 4-H days. I won the best-groomed contest in Wilson County.” I am interested that she takes on your voice, the first person. She found her way of adapting to your death. She made scrapbooks. She was in her fifties then, when she lost her youngest son, the same age I am today.

Lately I have been studying this picture as though it contained some answer, a missing piece. What is the new story? People live inside us. You live inside me. My father. The hero. And now that child. That boy. He lives inside me, too, and he looks out into the future with such fresh hope that it breaks your heart. He doesn’t know what is ahead of him. I can see it in his eyes. He doesn’t know all the wonders ahead, the darkening clouds of a Kansas storm, the war and the brilliant blue sky above the Mojave Desert, the majesty of the Grand Canyon, snow and trees, falling in love, handfuls of rice, his first-born child, the smell of frying fish, the smell of a plane, the blue-black horizon. Anything could happen. Everything is possible.

It is all an unknown, then and now, a beautiful mystery.

With love,

Your daughter Sharman

This letter was originally published here.