Echoes of History: Charles Lummis' Wax Cylinder Recordings

Artbound revisits early Los Angeles to explore one of its key and most controversial figures: Charles Fletcher Lummis. As a writer and editor of the L.A. Times, an avid collector and preservationist, an Indian rights activist, and founder of L.A.’s first museum, Lummis’ brilliant and idiosyncratic personality captured the ethos of an era and a region. Watch Artbound's season eight debut episode, "Charles Lummis: Reimagining the American West," premiering Tuesday, May 10 at 9 p.m., or check for rebroadcasts here.

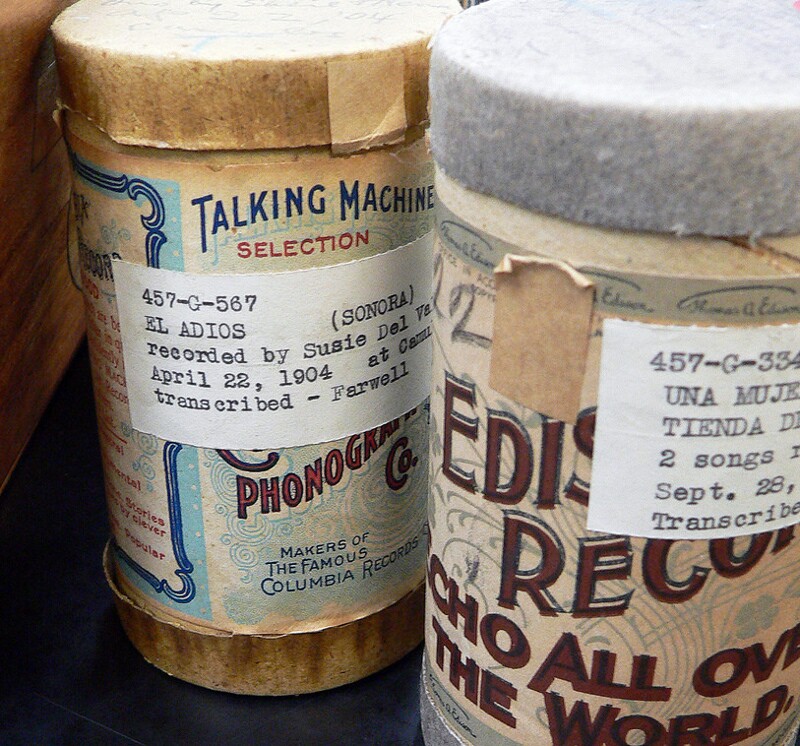

If you had chanced upon El Alisal, the stone craftsman home of Charles Fletcher Lummis, circa the early 1900s, you might have come upon the sight of someone singing into what would have looked like an inverted traffic cone. That horn tapered down to a stylus which, in turn, carved its way into a spinning cylinder of brown metallic soap, leaving behind tiny scraps of wax. Once complete, the cylinder could be played back on the same rig, with voices and instruments preserved via what was once the dominant recording system of early 20th century.

Invented by Thomas Edison in the 1870s and developed into a commercial product a decade later, wax cylinders were originally pitched as a dictation device, predating the modern tape recorder by nearly half a century. However, while they did become popular as dictation machines, far more people found entertainment value in them, using cylinders to record and play back the popular music of the day, or in the case of Charles Lummis, of the past (or at least, so he thought).

Lummis was one of Southern California’s most influential boosters at the turn of the 20th century: an impresario, a journalist, and most passionately, a documentarian of the Southwest. Situated in the arroyo that now borders Highland Park, Lummis began inviting friends and acquaintances over to El Alisal in late 1903 to record what he thought were traditional Mexican and Native American folk songs. He eventually produced over 450 cylinders in a few years, a remarkable feat for the era considering that he started around a year before composer Béla Bartók took an Edison recorder into Hungary to record folk songs, while Alan Lomax wouldn’t begin his storied field recordings of American song styles for another three decades. That collection, which includes hundreds of other cylinders that Lummis acquired from others, resides within the Braun Research Library at the Southwest Museum of the American Indian.

Lummis’ original goal, as he explicitly explained in his 1923 book, "Spanish Songs of Old California," was to save “the Old Songs from oblivion,” insisting that, “it is sin and a folly to let each song perish.” He was an unabashed nostalgist for a fantasy of a California he felt was on the verge of being wiped out by the forces of modernity, thereby obligating people such as himself to “save whatever we may of the incomparable Romance which has made the name California a word to conjure with for 400 years.” There’s a certain irony in Lummis, seeking to preserve cultures he thought were being lost to modernity, using an Edison cylinder, a veritable symbol of modernity itself. Moreover, as editor of "Out West," he was helping to promote Southern California in such a way to hasten the process of transforming the area into a modern metropolis.

Regardless, Lummis was never shy about embellishing his own accomplishments and with his song project, he boasted that his efforts were “barely in time: the very people who taught them to me have mostly forgotten them, or died, and few of their children know them.” High (self) praise but also likely overstated. It’s undoubtedly true that Lummis, in some cases, recorded the only extant versions of specific songs that exist today. However, in other cases, Lummis’ push towards preservationism was undermined by his amateurism as a music historian.

Musicologist Dr. John Koegel of CSU Fullerton first heard about the Lummis cylinders thanks to a late 1980s episode of Huell Howser’s California Gold television show. The collection became the center of Koegel’s graduate school research and he remains the leading expert on it. “Lummis had a particular kind of sound in mind… Spanish songs of old California,” he explains, pointing out that like most collectors, Lummis’ curatorial impulses favored some styles while rejected others. For example, the corrido tradition of narrative ballads, arguably one of the most popular and important Mexican song styles going back decades, is barely to be found in Lummis’ collection. Instead, he favored canciones, a popular lyric song style that could be found throughout the Southwest and one that Lummis romanticized as having roots that lead back to Spain.

However, when musicians sat in front of Lummis’ recording horn, they didn’t always explain to him what they were performing or where those songs came from. For example, a small number of the recordings were of contemporary Mexican theater music rather than the older folk songs Lummis thought he was preserving. In many cases, the songs were far from in danger of disappearing. “Some of these songs existed in popular sheet music at the time,” Koegel explains, adding that it was easy for Lummis to miss these things because “he didn’t go to Mexico regularly, there was no radio, and the recordings were just starting to be recorded in Mexico so it took them a while to come up.” For all these caveats, Koegel still notes that “no one collected as much as he did in California.”

That most of these cylinders have survived the past 110 plus years is nearly as impressive as the size of the collection itself. Wax cylinders are so brittle that even a sudden change in temperature can shatter them and the very act of playing them is a destructive process since the stylus, if not weighted exactly right, will simply continue to shave off more wax from the groove. As Lummis toured with his collection extensively, he frequently played his cylinders to audiences but in the process, wore a few of them to the point of inaudibility.

Since the early 1990s, a small group of audio preservationists have volunteered their time to both transcribe the Lummis collection and, at times, restore broken cylinders within it. One of the central people involved has been Dr. Michael Khanchalian, a dentist who discovered a knack for repairing wax cylinders at age 12 and has since become a world renown specialist in the field. As it turns out, dentistry and cylinder restoration draw upon similar skill-sets, and both require steady hands.

Khanchalian's home office is filled with a staggering number of late 19th and early 20th century phonographs plus hundreds of cylinder tubes and boxes. He picks up one Lummis cylinder he’s close to restoring and explains: “I started to figure out, if this thing is broken, how could I not only get it together but line up the grooves just right and try to get the thing to track.” As any given cylinder can have between 100 to 200 grooves per inch, the work is painstakingly meticulous and Khanchalian is obsessive about getting every detail right. “When I got good at it, I got dental wax companies who would actually mix special formulas, colors I wanted, then you mix and match like an artist to try to get the color right,” he says.

Often times, with cylinders that have cracked or shattered, there are missing parts and Khanchalian learned how to fill in the blank spots with compatible wax composites, and then how to re-groove them to get the stylus to track. Even though there’s no sound recorded in those patched sections, because cylinders normally spin at a rapid 120 to 160 revolutions per minute, “the mind just fills [the sound] right in, not a problem,” Khanchalian says. Once repaired, Khanchalian and his partners have taken pains to transcribe the cylinders to other media and over the years, they’ve gone from reel-to-reel tape to DAT to CD and now to hard drive.

By coincidence, he has a personal connection to Lummis; his wife’s grandmother and Lummis were good friends and that’s partially what convinced Khanchalian to volunteer his time over the last quarter century to slowly transcribing and restoring the Lummis collection. “I just started doing them, I don’t know how many by now. Couple hundred, I guess,” he says. “We got some great recordings of Charlie himself, talking to his kids, saying crazy stuff. He does this thing we call ‘the walrus.’ He’s recording somebody famous and then all of the sudden, he does this crazy howl he calls his walrus, just screaming into this thing.”

That was -- and remains -- the magic of recording.

What Lummis was discovering was the potential, power and pleasure in recording. As an audio archaeologist, he recognized the importance of using this then-novel medium as a way to document but there’s also something profound in being able to record your own voice to play back. The Lummis collection, a century later, continues to remind us why recording has always felt so revolutionary, whether one is capturing an indigenous folk song or the walrus roar of Los Angeles' preeminent eccentric.