Troubling History Repeating? Art Examines Parallels Between Japanese American Internment and Today’s Migrants

When Tania Candiani found the photo, she was struck first by the look of the woven cloth. In the black-and-white photo taken by Dorothea Lange at the Manzanar concentration camp, one of ten camps where Japanese Americans were forced to live during World War II, five women work on a loom strung from the high ceiling of an army barrack. The walls of the building are only partly finished. Above the women’s heads, naked wooden beams let in the elements: heat, dust, harsh sun. In other photos taken by Lange, the weaving women wear bonnets, scarves and masks to keep out the dust. In this one, their heads are uncovered. Four of them stand and the other squats as they weave strips of hemp fabric across a grid of thread, creating camouflage netting that will cover American tanks.

“The photo has a tremendous beauty because the patterns created in the nets, they look like a tapestry,” said Candiani, an artist from Mexico City whose work often investigates craft and labor. “The work these women were creating was really sophisticated and beautiful at the same time while they were living in these horrible conditions. I started reading about the story and immediately it created a bridge with the conditions of the migrants at the border right now.”

Candiani will recreate Lange’s photo this weekend, at the Frieze Los Angeles art fair, with the help of five performers, who, over the course of three days, will weave five nets. “We prepared strips of fabric with different kinds of camouflage colors: desert, jungle and sea,” she said, “because migrants come from everywhere.”

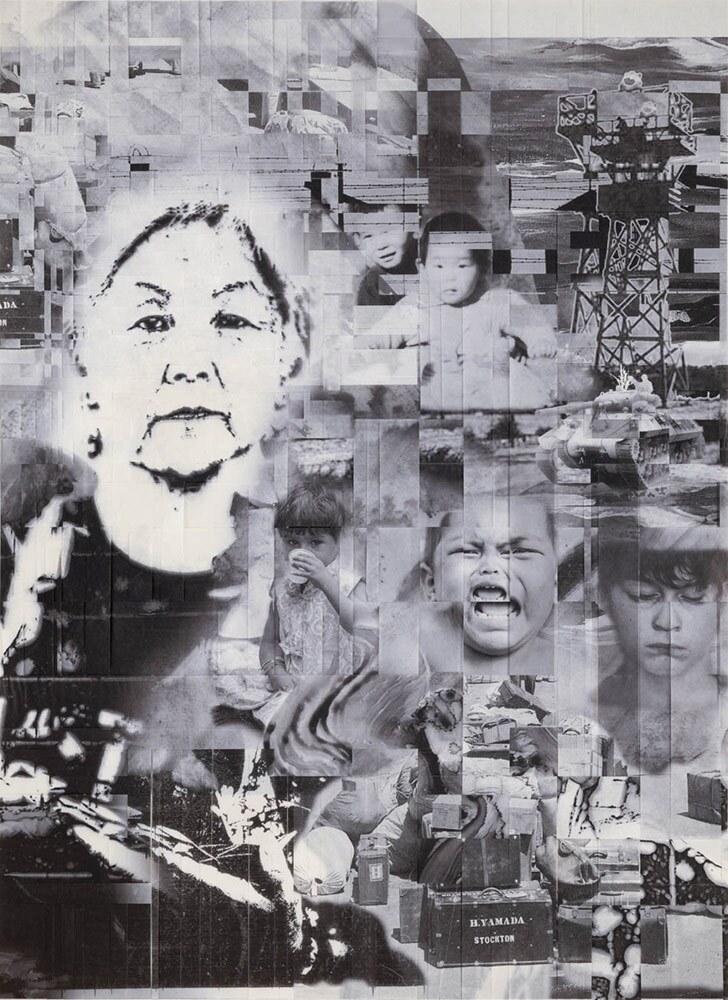

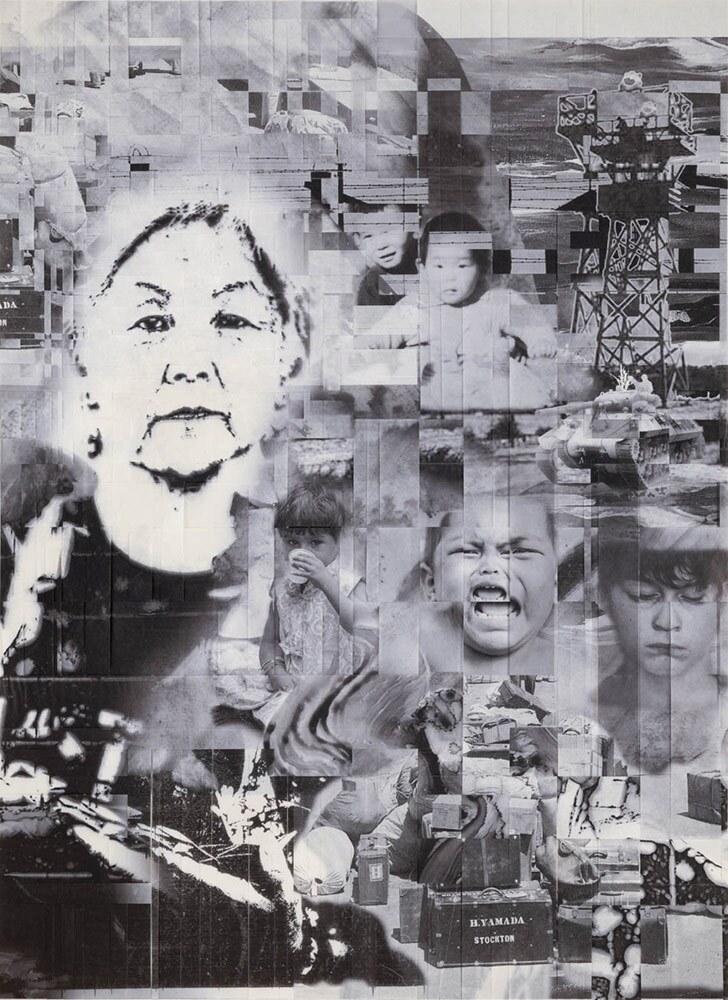

Japanese American artists and activists have also been speaking out about the connection between the World War II incarceration and the United States government’s more recent immigration and travel policies, especially the Muslim Ban and the detention and separation of families at the U.S.-Mexico border. In his new exhibit at the Japanese American National Museum, “Transcendients: Heroes at Borders,” artist Taiji Terasaki highlights some of them, while finding his place among them.

“Transcendients” has several distinct parts, half of which directly reference the U.S.-Mexico border. In the hallway leading to the gallery stand four sets of lenticulars, images that change depending on your vantage point. On the first one, “FORCED IN” turns into a black-and-white image of Japanese American families guarded by soldiers in front of a train that will take them to a concentration camp. “KEPT OUT” becomes a family of Latinx migrants with a young child behind the chain-link fence.

“Taiji had this vision that came from a very personal place, where his own family’s history is in those camps — his parents and his grandparents were all incarcerated during the war — so he had a very visceral reaction to what was happening, especially to asylum-seeking families who were being separated at the border,” said Emily Anderson, project curator for “Transcendients.”

Beyond preserving history, she explained, the Japanese American National Museum wants to remind people of the broader context surrounding the incarceration, that it wasn’t a sudden reaction to war breaking out between the U.S. and Japan, but the culmination of decades of prejudice and systemic racism. “There are alarming parallels that we can identify now, and we have a responsibility to share that story so that it doesn’t happen again,” she said. “History isn’t just stories, it’s stories with a purpose.” Though the specific laws are different, in both cases they’ve come with other-ing and fear-inciting rhetoric that has swept the country into tribalist hysteria. “Nobody is looking at facts or figuring things out, it’s just this gut-level, very primal fear that becomes an overriding paranoia,” Anderson said. “The target is constantly moving ... Whether people are afraid of Mexicans or Iranians or North Koreans or the Chinese creating the coronavirus, it’s just xenophobia, packaged as protection of the self against this ‘other.’”

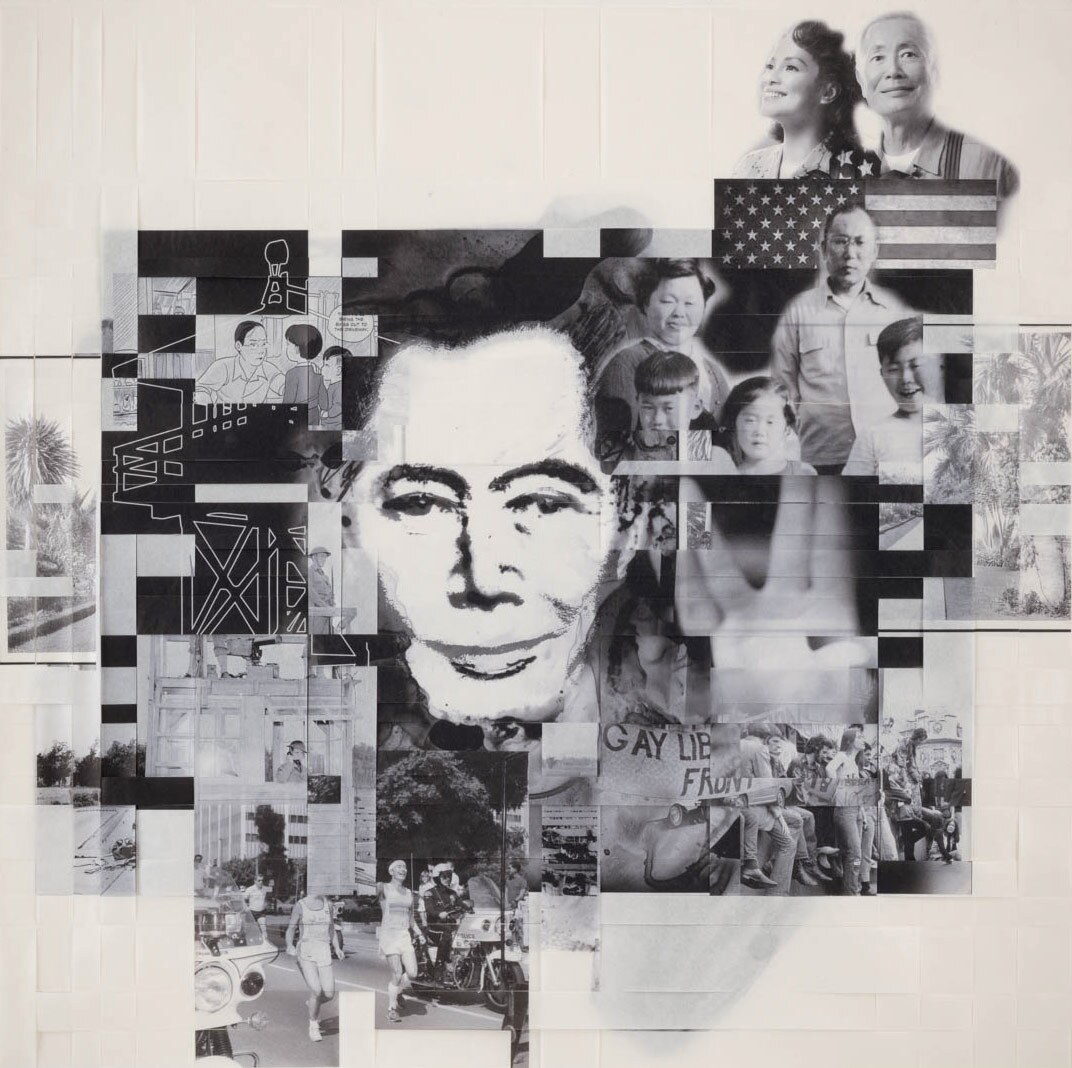

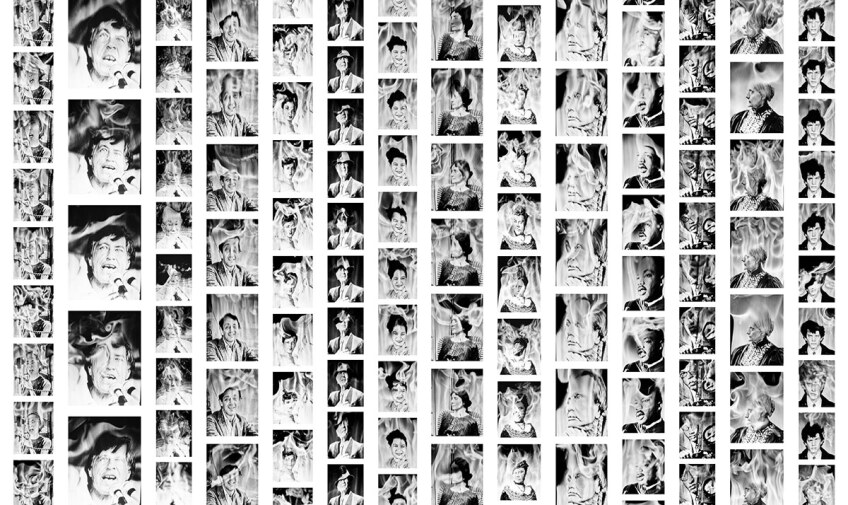

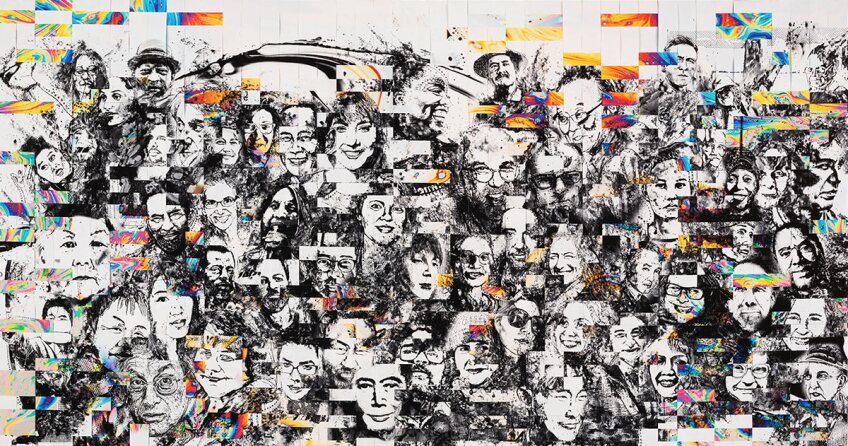

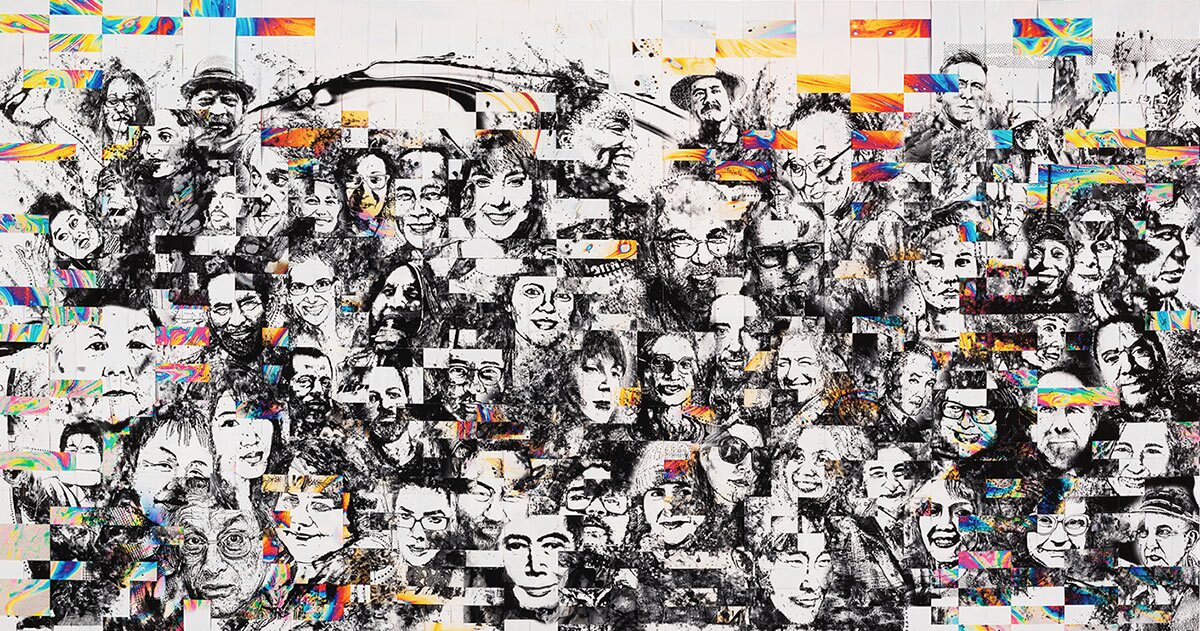

Past the lenticulars, “Transcendients” turns its focus to individuals. Memory boxes along the hallway wall honor the personal heroes of the volunteers who made them, drawn to the craft by word of mouth spread from Terasaki through local Japanese American community centers. Inside the gallery hang woven collage portraits of activists for causes ranging from antiracism to water rights to gardening. Among them are a few of the Japanese Americans who have been most outspoken about racist policy in recent years.

Likely the best known outside the community is George Takei, who wrote op-eds for The New York Times and The Nation, sharing his family’s incarceration story in protest of the Muslim ban and family separation. His graphic memoir, “They Called Us Enemy,” and his musical, “Allegiance,” which is fictional, extend the same mission. In “They Called Us Enemy,” Takei discusses the redress movement and the resulting apology President Ronald Reagan made in 1988 on behalf of the government for the incarceration. “That apology came too late for my father,” Takei writes. “He passed in 1979, never to know that this government would admit to wrongdoing.”

The Japanese American incarceration makes an especially good story for solidarity protest because of the government’s eventual apology, though the Supreme Court case upholding it as constitutional, Korematsu versus the United States, was not overturned with that apology. “In a cruel irony,” Takei writes in “They Called Us Enemy,” “the court struck down Korematsu as a mere side note in Trump versus Hawaii, the very same ruling that upheld President Donald Trump’s ban on immigration from Muslim countries.”

Along with Takei in “Transcendients” is Satsuki Ina, a writer, filmmaker and therapist specializing in the treatment of community trauma. She is also one of the co-organizers behind Tsuru for Solidarity, a group that brings displays of origami tsuru, which means cranes, to protests at active and proposed sites for detention centers because they want the incarcerated children to see the brightly colored birds, hear the voices and drums outside, and know that someone is thinking of them. Tsuru for Solidarity has protested alongside groups like Black Lives Matter, United We Dream and the ACLU, and Ina calls the intercommunity action healing. “Part of trauma that has been inflicted on people of color in the U.S. is that our connections with each other have fractured,” Ina said. “We’re trying to survive in our own silos, trying to protect ourselves, and we haven’t really connected with each other.”

Her poem “We Came Back For You” is also the focus of the film that plays in the gallery, projected onto a curtain of fog. “We came back for you because … we know mass incarceration,” it begins. “We came back for you because … we care.” The images, of adult and childhood Ina, of other children in camp, drift up on the fog like spirits in transit.

Ina, who was born during World War II at the Tule Lake Segregation Center, credits some of the Japanese American solidarity activism to unexpressed protest. “We were children, most of us were children in the camps,” she said. “The loudest protest was when we demanded redress, and then after we got redress, we kind of as a community went silent. It’s kind of like we got paid off. But this crisis of humanity at the border I think resonated with so many of us. The rhetoric was so similar that it didn’t take much to get the Japanese American community awakened.”

Working in the Japanese American community means constantly thinking about transience and preservation. We mark time by who has died: the issei, who immigrated from Japan and were adults during camp. Few nisei, the second generation, remain; my great-aunt, 22-years-old when her family was forced to leave their home on Terminal Island, is now 100. Takei, Ina, and Terasaki are all sansei, third generation.

“My parents and grandparents were incarcerated. Sometimes I can’t believe it,” said Terasaki. “But unfortunately that generation is passing away, and hopefully we captured enough of their memories.” Who will remind the country of what it has done, and what it has apologized for, once those who directly experienced it are gone?

Both Terasaki’s exhibit and Tania Candiani’s performance require a full-body presence. In the last part of “Transcendients,” which is also outside the museum and free to the public, you walk through a shipping container alone with a security guard. Projectors cast images onto each side, the past on the left and the present on the right, Japanese Americans, Mexicans and Central Americans, everyone incarcerated, you in the middle. After I walked through, the security guard, a man in his 20s, let me out into the sunlight. “It makes me madder every time I see it,” he said.

Candiani’s pieces sometimes include music, like the performance “Pulso,” for which she commissioned 210 women to beat old, pre-Columbian drums through the subway system in Mexico City. The Manzanar weaving piece, though, will carry only the quiet sound of labor. She’ll explain to the performers the story behind the Dorothea Lange photo, and she knows they’ll have their own additional reasons for participating, all of which will somehow influence the work. The fabric strips might swish like dry hands against each other as the women weave, or maybe they will make a harsher scratching like the surprisingly rough drag of sashiko thread through fabric. Maybe the wind will bring in the sting of dust. Maybe the next American apology won’t be half a century too late.

Tania Candiani’s performance, presented with Instituto de Visión, Bogotá, will run at Frieze Los Angeles February 14 to 16 at Paramount Pictures Studios. “Transcendients: Heroes at Borders” will be on display at the Japanese American National Museum until March 29, 2020.