The Westside Dance Movement That Laid the Foundation for West Coast Hip-Hop

The following series documents key aspects of life in Black Los Angeles, informed by the archives and work of Gregory Everett, and guided by Dr. Daniel E. Walker.

During the early 1980s, second to selling drugs, throwing parties was one of the most lucrative ways for people in the 'hood to make money. Young entrepreneurs who might have otherwise turned to the streets, invested in DJ equipment, assembled crews of promoters and began organizing parties for teenagers and young adults at houses, auditoriums, school lunchrooms, event halls, hotels and wherever else they could find the space.

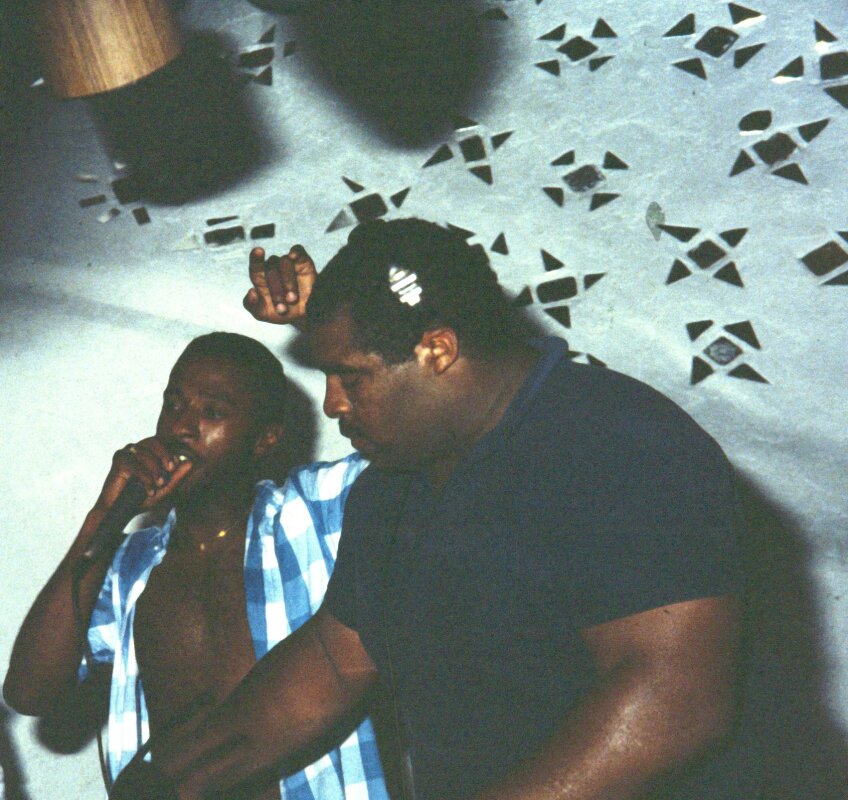

Led by a record store owner and DJ named Roger Clayton, Uncle Jamm's Army (UJA), was arguably the most successful dance promotion group that Los Angeles has ever seen. Fueled by a fast-paced, electronic version of early hip-hop, UJA began throwing parties at high schools and eventually sold out arenas.

"These guys were kids from the 'hood, who made a legitimate business, making more money than most hustlers in the streets," the rapper and actor Ice-T told Red Bull Music Academy in 2017. But they weren't alone. By the mid-'80s, there were dozens of these groups. "It was fiercely competitive," Gid Martin — co-founder of UJA — told Red Bull.

"[DJ groups] locked down the sports arena, same place where the Clippers played, and it'd be maybe, you know, 10,000 people partying on a Saturday night with no performers. It was just DJs and this new dance craze," comedian and actor, Alex Thomas recalled during an interview with KCET. East Coast hip-hop was just starting to take off but when New York acts like LL Cool J came to Southern California to perform at an Uncle Jamm's Army party, they opened up for the DJs. That's how popular the DJs were at the time.

Thomas was too young to go to the UJA shows but he danced to the music that they produced and went to 21-and-under parties that they influenced. During this time, teenagers like Thomas were being bussed from South Central to schools in the valley and L.A.'s Westside. "So now you got Black kids in the 'hood, listening to Duran Duran, [Adam and the Ants], all these songs," said 52-year-old Legend, a member of the Soul Brothers dance crew. He explained how the Brown vs. Board of Education decision led to schools in L.A. becoming more integrated. "Prior to that, all the dope high schools were in South Central like Manual Arts, Dorsey, Fremont. Those were the high schools for that time period. So now the Westchesters and the [University Highs], Fairfax, they start coming into play."

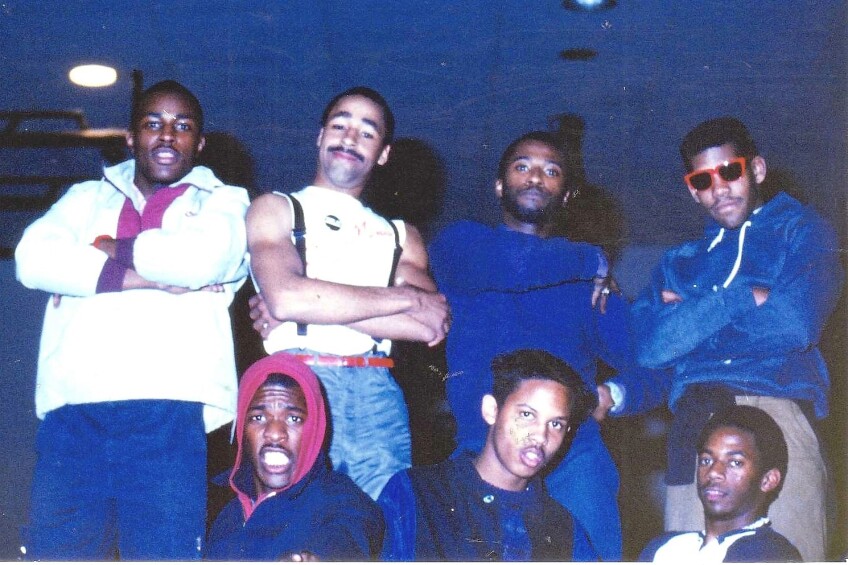

During the early '80s, aesthetics from the 'hood collided with the burgeoning punk, mod and ska scenes that exploded around the Fairfax/Melrose area and L.A.'s westside, resulting in high-top fades, Doc Martin creepers and "old man" suits becoming popular among Black youth. "We started wearing stuff like that in the 'hood," Legend chuckles as he reflects on his sense of fashion as a teenager. "I hate the early '80s. I looked like I was Eddie Murphy, Don Johnson and Rockwell all mixed in one."

"So we would all dress up like that. But we took that and branched that off into a scene," 52-year-old Vance Collins, another member of the legendary Soul Brothers explains during an interview with KCET. With the clothes from Melrose came a new style of dancing. "They called it Trendy Dancing," said Collins. Songs like Afrika Bambata's 'Planet Rock,' 'Technicolor' by Channel One and Egyptian Lover's 'Computer Love' — music that blurred the lines between techno and early hip-hop — became the soundtrack for this new Trendy Era. "It would be like 130, 140 beats per minute, real fast. And we would do these dances to it," said Collins. Dances like the poser, which came out of the ska scene, the prep, and the guest — moves that you still see today on some dance floors — were popularized during this period. "We would definitely do this dance called the wop," Collins remembered.

During the summer of '85, a DJ named MCG (Gregory Everett) caught onto this new scene. Everett and his lifelong friend Rick Aaron had already been throwing parties at high schools, houses and a club called Kingston 12 in Crenshaw for years under the name Ultra Wave. It was at Kingston 12 that summer in '85 when Everett began to notice the dance crews coming out of the Westside high schools.

"The Westside during this time was what the Black community of Los Angeles considered basically, but not officially; west of Western, north of Slauson, south of Olympic, all the way to the beaches. Black people who lived on the Westside were considered a little more well off than their Eastside counterparts," Everett and Aaron recall in "Clap Clap Wave (The Ultra Wave Story)," a short unpublished retelling of the history of Ultra Wave that the co-founders worked on last year and shared with KCET. Unfortunately, before further plans could be made, Everett died of COVID-19 in January.

The Westside is where Ultra Wave made a name for themselves and where both Aaron and Everett grew up. The two cut their teeth on a street in mid-city lined with single-family homes and lush green yards. "My grandmother lived on a street called Potomac Avenue, which is where we all grew up," Aaron told KCET. No DJ group would become bigger than Ultra Wave, catering to a crowd too young for UJA's 21-and-over parties.

That summer in '85, Ultra Wave outgrew the Kingston 12 and moved across the street to the Maverick's Flat, also known as the "Apollo Theater of the West," on Crenshaw Boulevard. On the first night at their new location, Everett cleared the dance floor and The Glitter Girls battled the Ultra Girls, laying the foundation for the dance battles that Ultra Wave became famous for.

Ultra Wave continued throwing parties at Maverick's Flat but eventually outgrew the space and expanded beyond Crenshaw Boulevard. That year, they threw themed parties at the Sheraton near LAX, the Airport Park Hotel in Inglewood and at the Elegant Manor in West Adams. By this time, their parties were averaging roughly 600 attendees, according to Aaron and Everett.

In a push to take over the Westside, Ultra Wave began DJing wherever they could. This included house parties, school dances, church functions, carnivals. Some gigs were paid, others they did for free. "Anything to get the name out there," Everett and Aaron recalled. By 1986, Ultra Wave had their eyes set on a larger venue on the border of Culver City with a gymnasium, theater and full-size stage called The Veterans Auditorium.

One problem though.

After a "mini-riot" occurred at one of UJA's parties at the Veteran's Auditorium, they banned dances. To get around this, Ultra Wave hired a "suit and tie representative" who had previously represented UJA when they had issues securing a venue, a guy named Ansel Simpson. They also joined a non-profit food bank called L.I.F.E (Love Is Feeding Everyone) and branded their parties as "dance competitions." To get into an Ultra Wave event, you had to bring a can of food.

Simpson successfully pleaded their case in front of the Culver City Council and Ultra Wave was given a shot to throw a dance competition. If things went well, the moratorium on dances at the Veteran's Auditorium would be lifted. To pack the auditorium and prove themselves, Ultra Wave needed a hit though. The capacity at the venue was about 800 but they planned to fill it with more than 1,000 people.

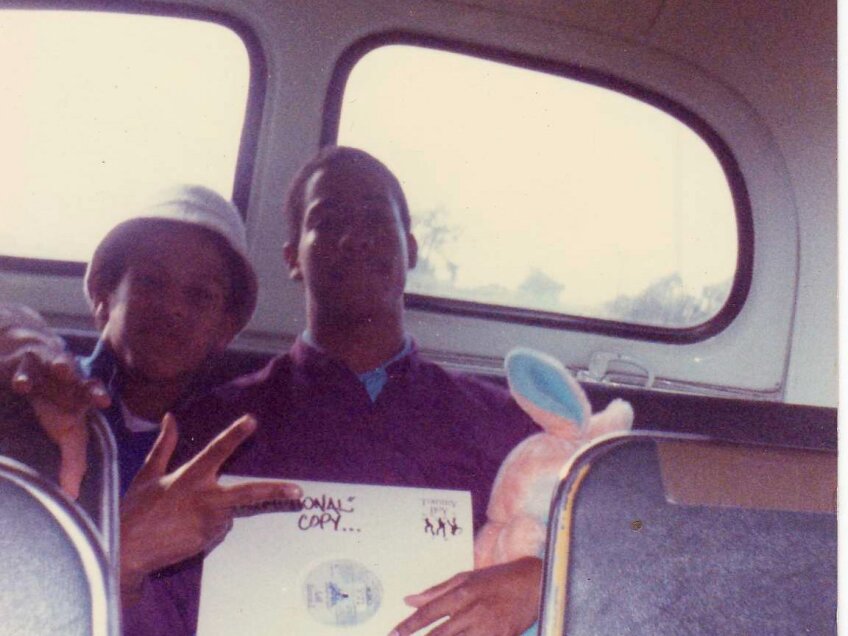

To promote their parties, Ultra Wave relied heavily on flyers and phone calls. "There was like pre-game hype for an Ultra Wave party because, you know, they would show up to school with these flyers to tell you either who was going to be dancing in the contests at the Ultra Wave, or if somebody was going to be performing," said Lawrence Gilliam, a Dorsey High student at the time told KCET. For months, Ultra Wave had been accumulating attendees' contact information in a book they called the Ultra Wave guest book. "The Ultra Wave Guest Book was a ledger that crew member Kevy Kev had brought to every dance since the Kingston 12 and had everyone sign who came to every dance," Aaron and Everett recalled in "Clap Clap Wave." One of the Ultra Wave DJs, DJ General Lee, was tasked with calling up everyone listed in the book before the party. "If they were not home or even if they were, he was to give the information about the dance to their parents. Most of them were going to need a ride anyway."

They also worked directly with student councils and produced audio commercials that played during school hours. By the mid-'80s, Ultra Wave was the most requested DJ service for LAUSD, according to Aaron and Everett.

After an impressive first show at the Veterans Auditorium, Ultra Wave decided to make the dance competitions that they experimented with at the Kingston 12, a key element of their parties.

"Basically, all of us instead of being in gangs, we were all in dance crews and dance groups. But it wasn't breakdancing. It was a new thing," Thomas, the dancer turned comedian, told KCET. Thomas was one of the co-founding members of the Romeos. "We were like, the first big group in the dance scene," Thomas explains. "When half of L.A. was either pop locking or breakdancing. We went with a whole new thing with this whole dance craze."

Even before the Romeos got big, Thomas had already made appearances on two of the hottest TV shows in America — "American Bandstand" and "Soul Train." "The beautiful thing about being on 'Soul Train' man, that was the beginning of my hustle/ networking life. Because I had a personality, I wasn't a dude that was just a dancer." Through dancing on "Soul Train," Thomas became friends with future star, Rosie Perez, which ultimately got him a spot on FOX sketch comedy series "In Living Color" in the early '90s, launching his acting career.

The Romeos got started in 1984, a year before the biggest years of the Ultra Wave dance competitions, when Thomas was a freshman in high school at Fairfax High. Some of the other founding members went to Westchester. "The girls loved us, we always had the best gear. I mean, we were getting suits tailored and shit like that, you know. Like I said, if we were singers, we would have been New Edition," Thomas joked during an interview.

"Dance crews would audition and if chosen be booked to battle on stage," Aaron and Everett explain in "Clap Clap Wave." Record executives and local celebrities like Ice T would judge the battles and attend the parties.

"They would just have all these high schools show up. And it would be these dance groups and they would battle, they would compete against each other. And each dance group came from each school." Collins, who admits that the Soul Brothers didn't start attending Ultra Wave parties until the tail end, explains. If you weren't on stage you were in the crowd wishing you were, Legend joked during an interview. "If not, you were working on honing your skills so you could make it up there one day," he said.

"Not only were there like, scheduled onstage dance battles with groups with routines but there would also just be impromptu dance battles on the dance floor, " Gilliam, the student that went to Dorsey at the time, recalled. Gilliam never found a dance group to compete with during Ultra Wave but he attended all the parties and eventually formed a group of his own called the Luv Nutz. "For the Westside of L.A., [Ultra Wave] was like the preeminent party or dance." Gilliam recalled a vivid memory of dancing at an Ultra Wave party and then climbing out of his sweat-soaked clothes after returning home.

While UJA parties were more of a melting pot of different types of styles, kids that went to the Ultra Wave parties on the Westside generally looked the same:

"Everybody looked like they were from England for a minute," Legend joked.

"We almost had like a mod white boys kind of look to our stuff," Thomas said. "My family when I would go to the family functions would be like 'what...is...this...n*gga…wearing?' Because it was mixed with white boy style, you get what I'm saying?"

In addition to playing ska and punk records, dance crews battled to that electronic hip-hop sound that artists like Egyptian Lover pioneered. "That's one thing that the Trendy Era, the Ultra Wave era, even the Uncle Jamm's Army era because of Egyptian Lover [all had in common]. We all had that computer-driven music. You know that robotic sound," Legend said.

People on the west coast were aware of east coast hip-hop acts like Run DMC, but there wasn't anybody on the west coast making music like that yet. "We knew about hip-hop. We all knew what 'Rapper's Deligh't was, but it just wasn't our thing here," Thomas said. In Los Angeles, households were just coming off of listening to disco, funk and other dance music. "Soul Train," which was shot in Hollywood, was the biggest show on television. The mid-'80s were also the golden age of drum machines and synthesizers. All of this contributed to the early west coast hip-hop sound.

Within eight months, Ultra Wave's attendance grew from 80 to 2,000 attendees. And thanks to their partnership with the non-profit, L.I.F.E, they were able to feed up to 100 families per week with all the donations they were collecting at parties. Ultra Wave made sure that the food went to the primarily-Black South Central at one of L.I.F.E's distribution centers on Western Avenue near Vernon, rather than the predominantly white Culver City where they held the majority of their most successful parties. As the son of a Black Panther, Everett "saw feeding the community as carrying on the legacy of the Panthers," the co-founders of Ultra Wave write in "Clap Clap Wave."

Ultra Wave continued putting on dances once or twice a month through 1986. The majority of the money they made was reinvested back into the business to secure more turntables, lights and records. Eventually, they got to the point where they DJ'd multiple events on the same day. In 1986, they were able to put a deposit for an event to be held on every holiday for the year.

"The cool thing about our thing was, it wasn't violent, and it had nothing to do with gangs and drugs. And that was huge at that time," Thomas said. People are sometimes shocked that he was able to avoid gangs growing up in Los Angeles during the 1980s.

As the '80s progressed, street gangs began to take over the party scene and it grew violent. "There was a dance group that turned into like a gang group called the Sex Jerx. And it was another gang called The Pozerz. The Sex Jerx and Pozerz would fight just like Bloods and Crips fight," Craig, the third member of the Soul Brothers said during an interview. Many of the members of Ultra Wave's own in-house rap group, Too Damn Fresh, would go on to become Rollin' 60s Crips, according to Everett and Aaron. In Craigs' words, gangs have always been embedded in Los Angeles hip-hop. "That's where you got cats like NWA," said Craig. The founding members of the pioneering west coast rap group were all involved in the electro hip-hop scene before gangster rap was created.

"They may not have looked like gang members while at the party, but catch 'em' in the hood and you knew what was up," Everett and Aaron write in "Clap Clap Wave". Other crews like UJA had similar problems. "Crack and gangbanging took over," Dwayne Muffler, a promoter with UJA during the '80s told KCET during an interview when asked why parties slowed down. "When mufuckas started shooting, and when crack hit the streets. It just wasn't the same anymore. Wasn't fun anymore."

"The gang scene made throwing parties like that dangerous." Muffler said. In the past, fighting was common, but the DJs found that putting on the right record could end a brawl. Eventually fights turned into shootings though. "The gangs they used to fight. Okay, no problem. We got the record for that. Well, there was no record for shooting," said Muffler.

Local police also became an issue. "You couldn't do nothing in L.A. without getting accused of being a drug dealer," Muffler told us. In 1987, LAPD Chief Daryl Gates launched Operation Hammer, which sent more than a thousand officers to South Central to crack down on gangs.

By 1987, a financial dispute led to the end of the dance competitions. Other parties like Jam City sprang up, continuing the Westside Trendy Era into the '90s. By '88, NWA released "Straight Outta Compton," officially launching the west coast gangster rap era. During the '90s, many of the dancers that competed at Ultra Wave parties or attended them — like the Soul Brothers and Groover Ken from the Groovers — went on to become back up dancers for hip-hop and R&B groups. Others like Alex Thomas, Regina King, Nia Long and Tyra Banks went on to have careers in the entertainment industry. Or became successful lawyers and business people. Looking back, Aaron says that's one thing that separated Ultra Wave from parties like UJA. "We were the private school yuppie promoters," Aaron told KCET. It was a Westside thing.

Despite having an undeniable impact on the trajectory of hip-hop in Los Angeles, the Trendy Scene has remained relatively underground. But unlike most of the DJ groups that they competed with, Ultra Wave memorialized their parties. Everett wasn't only a talented DJ, MC and promoter, he was also a filmmaker who knew the importance of documenting significant moments in history. "He was a historian," Jefferey Everett, Gregory's son, said during an interview with KCET. "It was important to have video evidence of what he did."