The Meaning of a Mixtape: How Musical Compilations Elevate Overlooked Communities

A point of discovery, an archive of history, a portal into an underground yet revered music scene — multi-artist compilation albums often elicit shared experiences among listeners and conjure memories of time and place.

For about 70 years, music collectors and archivists have used the compilation, or mixtape, as an art form to preserve and celebrate the past — from Harry Smith's 1952 project "Anthology of American Folk Music," which collected regional gospel, folk and blues 78s recorded between 1927 and 1932, to Habibi Funk, a German reissue label launched in 2012 dedicated to compiling diverse tracks from the Arab world.

In Los Angeles, compilations are windows into the Latinx music landscape, spanning rock, punk, disco and soul, genres and cultures that have often been marginalized or ignored in mainstream media.

Artist Rubén Funkahuatl Guevara's compilations helped cement the importance of Chicano rock and punk history. Iconic radio host Art Laboe's "Oldies but Goodies" doo-wop compilations became part of the backdrop to Southern California's lowrider culture. Young DJs in East L.A. studied compilations by Frank Del Rio and Pebo Rodriguez, admiring the art of the cross-fade.

These compilations were different from major record labels', cash-grabby, "best of" and "essentials" albums, instead celebrating cultures and documenting lesser-known histories.

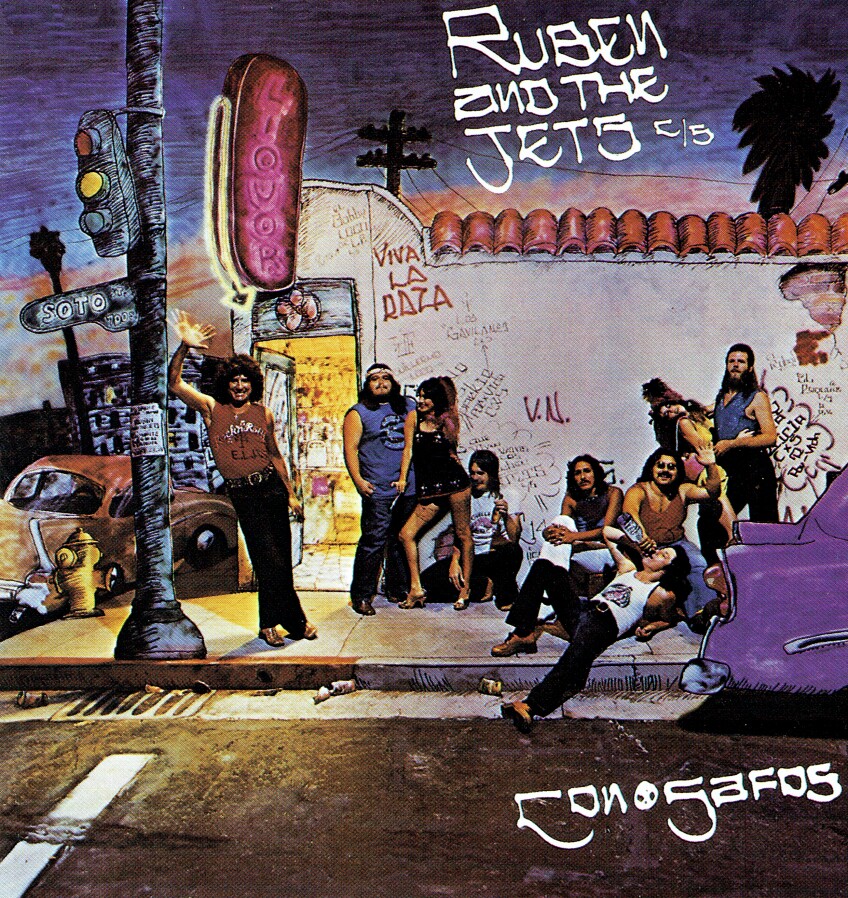

Born in Boyle Heights and raised in Santa Monica, Guevara, a Chicano singer, songwriter, activist and performance artist, gained fame in the 1970s with his experimental band Ruben & the Jets, produced by Frank Zappa. In 1976, he was commissioned by Rhino Records — the L.A. label that made its name producing cross-licensed, multi-artist compilations in the 1980s and '90s — to record doo-wop versions of "The Star Spangled Banner" and "America the Beautiful."

Guevara later approached Rhino founder Richard Foos with an idea — launching a subsidiary label devoted exclusively to Chicano and global Latino rock, which Guevara called Zyanya Records.

Under the Zyanya label, which means "always" in Nahuatl, Guevara produced five compilations in the early 1980s and '90s, showcasing the best of East L.A. Chicano rock history, top musicians of the punk and new wave scene and global rock-en-español groups.

Through his archival work, Guevara "acted as an 'on the ground, grassroots historian who had lived the scene,'" says Josh Kun, an author and music scholar at USC.

Guevara first set out to "document the little known contribution Mexican American musicians have made to the body of American and Chicano rock 'n' roll," the artist said via email.

Inclusion on Guevara's compilations 'validated that we were part of the club — Rubén's club.'Tony Marsico, bassist for the Cruzados

The result was 1983's "The History of Latino Rock: 1956-1965," which focused on the most famous of L.A.'s Chicano rock bands and singers with national hits, and popular local musicians including Ritchie Valens, Cannibal and the Headhunters and Little Julian Herrera — "considered the first L.A. Chicano R&B star in the 1950s," Guevara said.

Guevara's "Los Angelinos: The Eastside Renaissance" compilation released in 1983, starred important fixtures from the Southern California punk and new wave scene including the Plugz, Thee Royal Gents, the Brat, bands that raged against injustice with politically charged songs.

Guevara's compilations were an East L.A. music history lesson, says Cruzados bassist Tony Marsico, who joined the Plugz in the 1980s. (A later iteration of the Plugz, the Cruzados, formed in 1984).

The Plugz' "La Bamba" and the Cruzados' "Flor de Mal" are featured on Guevara's, "Ay Califas! Raza Rock of the '70s and '80s" along with songs from Santana and Los Illegals. Released in 1998, the compilation hones in on important Chicano and Latino bands from California.

Inclusion on Guevara's compilations "validated that we were part of the club — Rubén's club," Marsico adds.

Guevara's 17-track "Reconquista! The Latin Rock Invasion" examined songs with strong socio-political messages around oppression and corruption by global rock-en-español bands including Los Fabulosos Cadillacs from Argentina, Seguridad Social from Spain and Santa Sabina from Mexico.

Although the bands on "Reconquista!" were well-known,"at the time, no one had pulled them together into one place before," Kun says.

Through his Angelino Records label, Guevara created the collaborative "Mexamérica" CD in 2000. The album convened bands from Mexico City, Tijuana and East L.A. fusing punk, hip-hop, soul and spoken word to address issues of immigration, Indigenous rights and cultural difference. The purpose of the concept album was to break down what Guevara calls "the Great Pocho Wall," which "divided Mexicans and Chicanos and to create together a new nation of mutual respect and consciousness."

Listen to a playlist curated by Rubén Funkahuatl Guevara below:

Guevara's compilations provided a major cultural service, says Kun. "They were game changing … No one was compiling Spanish language alternative rock and punk and new wave in Los Angeles at the time and actually saying, 'This is a scene that's telling a story. And if we don't compile this, it might be forgotten.'"

Mixtapes and compilations also played an important role in East L.A.'s DJ scene, says Gerard Meraz, a Chicano studies instructor at Cal State Northridge. Meraz, who is also a DJ, got his start in the 1980s hosting backyard parties across East L.A.

Track selection, the blending of songs, the journey created on a mix — those were the techniques Meraz and other budding DJs studied on late 1970s and early '80s mixtapes by artists like Frank Del Rio and Pebo Rodriguez, resident DJs at Circus Disco, the iconic Hollywood club that served as a safe space for LGBTQ Latinx communities.

DJ compilations, including the electro "My Forbidden Mixer" released in 1984 on vinyl, became popular through word of mouth, Meraz says.

In the early 1980s, it was challenging to make copies of cassette mixes. But by the mid-to-late 1980s, "the technology to dub cassettes became more affordable … by the '90s, the rave scene was in full swing and the record stores were all carrying either cassettes or CDs by independent DJs putting them out as mixes or promo tools."

Soul music scholar and vinyl collector Ruben Molina began burning homemade mixtapes after his mother gifted him a record player with an attached 8 track recorder in 1970. "We would take those and put them in our cars so we could carry our music with us instead of listening to the radio," Molina recalls.

"Oldies" or doo-wop, and romantic soul from the 1950s and 60s, provided the soundtrack for Southern California's lowrider culture in L.A.'s Chicano communities. Molina has a theory for why the genre is so beloved: with their candy paint jobs and custom upholstery, lowriders needed a sound to match the vibe. "When we were cruising, we had to have this mid-tempo or even downtempo music to go with the car, to go with the cool," Molina says.

Compilation albums were a method of disseminating Southern California's lowrider "Chicano sound" across the U.S. and abroad, Molina says. In the 1990s, the Chicano lowrider fad hit Tokyo youth, "with car clubs and cholo fashion becoming the rage," Guevara wrote in his autobiography, "Confessions of a Radical Chicano Doo-Wop Singer." The Japanese lowrider trend was started in part by Shin Miyata, who first discovered Guevara's "Los Angelinos" compilation in a Tokyo record shop in the 1980s.

In 1959, radio personality Art Laboe released his first "Oldies but Goodies" compilation, featuring artists including the Penguins, Shirley & Lee and Etta James. Another popular R&B disc jockey Dick Hugg, known as "Huggy Boy," found a large audience in East L.A. for his radio programming and "Rare R&B Oldies" compilation series.

At swap meets across L.A., unlicensed, bootleg oldies compilations were in high demand. Anthony Boosalis sold his East Side Story compilations of doo-wop, R&B and soul music at El Monte's Starlite Swap Meet. Initially released as 8-Track tapes, the twelve-volume compilation of soul music grew in popularity as technology changed, and were later sold in vinyl and cassette formats through the 1970s and '80s. The albums were also loved for their iconic covers with photos of East L.A. Chicano youth.

Even as mass digitization makes music free and readily available with a single click on platforms like Spotify and SoundCloud, compilations and mixtapes are still coveted as snapshots of time, of home, family and cherished memories, passed from generation to generation.

Filmmaker and DJ Melissa Dueñas grew up on oldies music. In 2015, she began her East Side Story Project, now a multi-platform initiative to unearth the history behind the once-mysterious compilations and pay homage to oldies culture among Chicanx in L.A. and Southern California.

Through Instagram, she quickly found an eager following of dedicated East Side Story fans, hungry to dig into the backstories of the cherished compilations.

Although East Side Story volumes are now hard to find and financially out of reach for many, "you can't put a price on the memories attached to these records," Dueñas wrote in a 2017 post. "These collective memories live on as records trade hands and we continue to share this music."