The Dunites: Building a Utopia in the Oceano Dunes

Ever since her childhood in southern San Luis Obispo County, Linda Austin has always felt an affinity for the Oceano Dunes. "There is just a force there that draws people in," said the Oceano Depot Association president, who remembers camping out in the dunes and sliding down the sand on an old feather mattress. "There's some kind of magic. I don't know how to explain it. It's just there."

The same undeniable attraction brought the Dunites to the Oceano Dunes. During its heyday in the 1920s and '30s, this bohemian community sandwiched between Pismo Beach and Point Sal was home to the likes of artist Elwood Decker, poet Hugo Seelig and revolutionary-turned-publisher Gavin Arthur, grandson of U.S. President Chester Alan Arthur -- attracting such high-profile visitors as avant-garde musician John Cage, authors John Steinbeck and Upton Sinclair and photographers Ansel Adams and Edward Weston.

"They were ... a group of individuals, 'individuals' being the operative word, who wanted/needed to live outside the normal parameters of social living," explained Jan Scott, collections curator for the South County Historical Society. "I don't think they chose the county as much as the county chose them."

Dunite historian Norm Hammond first discovered Oceano during a cross-country motorcycle trip in 1960. "I saw this place and thought, 'You know what? I want to live here,'" recalled Hammond, who returned to the Central Coast eight years later.

His introduction to the Dunites came in the form of Luther Whiteman's 1947 book "The Face of the Clam," a fictionalized account of dune life similar to Steinbeck's "Tortilla Flats." Then, in 1974, he came face to face with one of the community's last surviving residents.

"One day I'm hiking around in the dunes and I see a pillar of smoke coming out of this willow thicket," Hammond said. Crawling through the carefully interwoven branches on his hands and knees, he emerged to discover astrologist Bouke "Bert" Schievink at home.

"He looked at me, acknowledged my presence and turned back to what he was doing.... So I just left," the historian recalled. "Some months after that ... there was a big article in the (news)paper that the last of the Dunites had died.... That got me thinking."

As Hammond details in his 2004 book "Oceano: Atlantic City of the West," the Chumash people were the first to populate the Oceano Dunes some 10,000 years ago. Although Portuguese explorer Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo surveyed the dunes in 1542, it wasn't until 1769, when Spanish explorer Gaspar de Portola led an overland expedition through the Central Coast, that Europeans laid a claim to the region.

The town of Oceano was created roughly a century later, the agricultural area's growth aided by the arrival of the railroads in the 1880s. Turn-of-the-century developers jumped at the chance to turn Oceano into a coastal playground.

Unfortunately for the investors who purchased plots in the planned communities of Oceano Beach, Halcyon Beach and La Grande Beach -- advertised as "the future Atlantic City of the Pacific" -- shifting sands made accessing that land difficult and discerning property lines nigh impossible. By 1915, signs of dune development had all but disappeared.

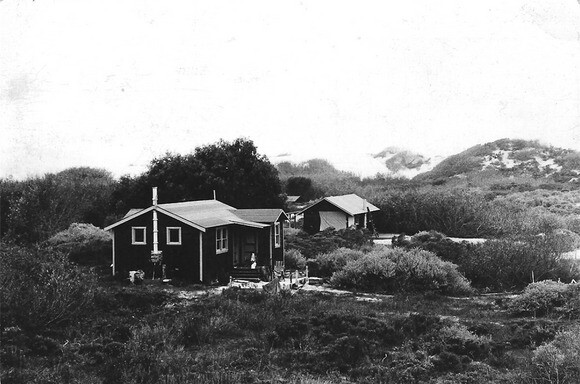

Meanwhile, a new kind of community was coming into being in the dunes -- a ramshackle cluster of cabins populated by artists, hermits, mystics, nature lovers and Lemurians. (The latter believed the long-lost continent of Lemuria would one day resurface from the depths of the Pacific.)

According to Hammond's 1992 book "The Dunites," Spanish-American War veteran, adventurer and poet Edward St. Claire was among the earliest Dunites -- also known as "Sandduners" or "Duners" -- along with such colorful characters such as Slim the Aussie, "Strongman" Paul Henning and George Blais, a reformed alcoholic who preached nudism, vegetarianism and sleeping under the stars. Subsisting primarily on fish and large, plentiful Pismo clams, they saw the dunes as a place of solitude and spiritual enlightenment.

According to Scott, the Dunites fell into two main groups: "the artists who wanted the freedom to live as and be who they chose to be, creating as they went, and the castoffs of the Depression, who had little or no choice about where to live. The beach was it."

Perhaps the highest-profile Dunite was Gavin Arthur, born Chester Alan Arthur III. At times an actor, author, astrologer and sexologist, "He had a very rich and varied life," said Atascadero resident John Reid, who's working on a biography of Arthur, "Gavin Arthur: Counter-Culture's Renaissance Man."

Rejecting his aristocratic roots, Arthur moved to Ireland in the early 1920s to aid the Irish Republican Army in its battle for independence. "He connected with Ella Young and she became one of the most influential people in his life," Reid explained, renewing that relationship when the Irish poet emigrated to the United States.

Young later became known as the godmother of Moy Mell, the utopian commune Arthur built in the dunes in the early 1930s. The name means "Pastures of Honey" in ancient Gaelic.

Like nearby Halcyon, a cooperative Theosophist colony established in 1903, Moy Mell was a mecca for intellectual, spiritual and social reformers, attracting such distinguished visitors as Indian mystic Meher Baba and Italian-American perfumer Princess Norina Matchabelli. Eccentric Dunites such as Arther Allman, a wood carver, writer and illustrator whose dwelling resembled a South Seas island hut, were another powerful draw.

"It was Gavin's dream to combine all these aspects, these different points of view" in a magazine, Hammond explained, which he dubbed "Dune Forum." It was assembled at Moy Mell and printed in San Francisco.

Contributors included composer Henry Cowell, poet Robinson Jeffers and writer-physician Havelock Ellis, as well as Seelig and other Dunites. Arthur and his associate editors, including Hollywood screenwriter Dunham Thorp, also wrote pieces. (Thorp's daughter, Ella Thorp Ellis, later wrote about her experiences among the Dunites in her 2011 memoir "Dune Child.")

"He saw this as a western version of the New Yorker," Reid said of Arthur, noting that the publisher's mother was among the magazine's strongest supporters. "Every time they published an issue, she would provide a case of champagne from Carpenteria," Reid said.

In the end, Dune Forum's steep subscription price -- 35 cents an issue -- proved its downfall, Hammond said. Six months after it started, the magazine published its final issue in May 1934.

The Oceano Dunes saw a brief building boom in 1938 when the Norwegian freighter Elg ran aground just off shore of the dunes. In their efforts to break free, the crew tossed more than 146,000 board feet of lumber overboard, which Arthur and his fellow Dunites used to fix up their cabins.

World War II changed the landscape even further. Since the Oceano Dunes were considered a strategic landing site for the Japanese, Arthur offered the use of Moy Mell to the U.S. Coast Guard.

By the early 1950s, the Dunites -- which at one point had numbered about 35 people -- had dwindled to just a few. With Schievink's death in August 1974, followed by the burning of his cabin weeks later, "the sun set on what little was left of the Dunite era," Hammond wrote in "The Dunites."

Today, all that remains of the Dunites is art, books, photographs and everyday artifacts such as clamming forks and cooking pots. The only surviving Dunite structure is Arthur's former home, known colloquially as Gavin's Cabin, which was moved to town in 1946.

The 12 by 30-foot wooden structure served as a rental property for about 15 years before owner Harlis Wall asked Hammond, then a firefighter, to burn it down. "I said, 'No.... I can't do that because it's a historical structure,'" Hammond recalled, so Wallis agreed to spare the cabin.

Finally, in September 2010, the cabin was moved four blocks to the Oceano Train Depot, already home to a 1940s boxcar and a turn-of-the-century caboose. Now Austin, Hammond and the Oceano Depot Association are raising funds to restore the cabin to its previous condition.

"We're preserving for the future all this history," explained Austin, who organized the first-ever Dunite Days, held at the Oceano Train Depot in early June, as a fundraiser. "It's such a fascinating era ..."

Hammond said the legacy of the Dunites "symbolizes man's eternal quest for an utopian life style, something that's better than what we know. Here was a democratic society ... in a setting that's hard to beat."

"I think that harmonizes with a lot of people," he added. "Certainly with me, it does."

Dig this story? Sign up for our newsletter to get unique arts & culture stories and videos from across Southern California in your inbox. Also, follow Artbound on Facebook and Twitter.