The Avant-Garde at the Orange County Museum of Art

Avant-garde movements throughout art history have tried to define and redefine the concepts embodied by contemporary art. From the Dadaists in the early 1900s to the street artists in the 1980s, avant-garde art has been an important foundation of accepted rebellion in the practice of art.

In Orange County Museum of Art's recent exhibition "The Avant-Garde Collection," the museum takes a look at the ever-evolving definition of avant-garde as it is represented through their permanent collection. Curator Dan Cameron finds it a fascinating study into the state of mind of contemporary artists within each limited era of art; from cubism and abstract expressionism to pop art, performance art and installation work. Avant-garde artists often are inspired by the artwork and movements that have come before them, and use the past as fuel to react in direct opposition to what has come before. Looking back on the momentous works of art from any important avant-garde movement, one can find significant and interesting visual relationships between the previous movements and the cutting edge reactionary work that follow.

"Avant-garde communicates nothing at all about the quality of the work over time, nor does it adhere to any style or movement," Cameron states, "providing a sound reason for why one should probably avoid describing the permanent collection of an art museum as essentially avant-garde." And yet, OCMA has come into possession of over 100 or so works that are inarguably avant-garde at the time of the creation, regardless of how favored they may or may not be, looking back at them. Cameron says that these works depict a decisive break with an existing order of representation and technique, placing the maker at the forefront of contemporary art of his/her time, and shifting the "avant-garde burden onto the shoulders of a new generation."

"The Avant-Garde Collection" exhibition is designed in somewhat of a chronological order, starting in the early 1900s with a painting by a Los Angeles native, Stanton MacDonald-Wright, one of the forefathers of Synchromism, an abstraction-based movement surrounding color theory. MacDonald-Wright worked with many Southern California artists through his work in the WPA program, including Hans Guztav Burkhardt, Richards Ruben and Jay DeFeo -- all of whom are also exhibited in the first part of the exhibition at OCMA.

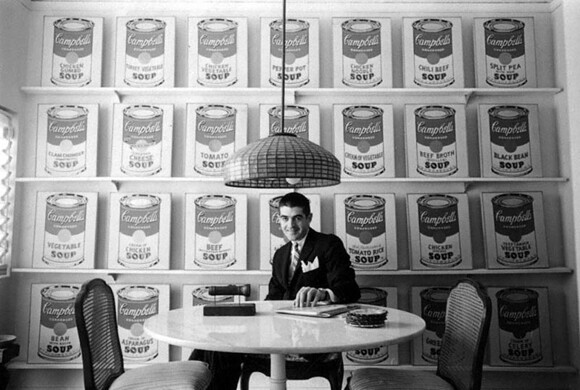

The collection has a thorough timeline exhibited through its acquisitions, and takes special attention to illustrate large and small shifts between inspiration and motivation between artists and movements. The 1950s brought the genius of Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg to the avant-garde limelight, whose abstraction and figurative work set the stage for a number of reactionary cutting edge movements that followed.

"The Avant-Garde Collection" shows strength in its presentation of California's 1950s and 60s artwork, including early Light and Space works, pop art, and conceptual works from this time period. Key players of this time period, like John Baldessari, Larry Bell, and Craig Kaufamn were present, along with lesser-known artists. Southern California earned its place in the art world around this time, bringing a serious yet distinctly California style to the larger art scene, and redefining, yet again, what avant-garde is.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Robert Irwin, Ed Kienholz and Chris Burden represented the cutting edge and genre-defining artwork coming out of California, though all very different in aesthetics. California's art scene was growing to be rival that of New York during this time, though with a different style all together, according to Hunter Drohojowska-Philp, author of Rebels in Paradise: The Los Angeles Art Scene and the 1960s. Drohojowska-Philp talked to public radio in 2011 about her book, and further supported that this time period was pertinent to placing L.A. on the art world map. L.A. and O.C.'s art scenes embodied a relaxed and vibrant mood, inspired and unique, in this new creative mecca. "I really was struck by the boldness of their decision to stay in Los Angeles when they could have gone to New York, and the way they all felt -- they couldn't grow and do what they needed to do for themselves as artists, in New York," Drohojowska-Philp said. "They needed the freedom and the permission of Los Angeles, where there were few galleries and collectors and no museum. There was no infrastructure, so they could do what they wanted."

Avant-garde art has been made in Los Angeles since the early 20th century -- though we may forget that fact looking at contemporary art today. Its classification under the category of avant-garde takes time to reflect on. In the film The Cool School, focuses on a small group of influential artists of the 1950s and 1960s in Los Angeles, surrounding one particular art institution, the Ferus Gallery. The artists involved in the Ferus Gallery are still some of the most influential and innovative artists in California art history -- many of whom are also exhibited in OCMA's "The Avant-Garde Collection."

According to renowned theorist and famed art critic Clement Greenberg, in his most famous essay on avant-garde and kitsch from the published essay, "Avant-Garde and Kitsch" in the Parisian Review in 1939, avant-garde is constantly only in search of one thing, absolute. "It has been in search of the absolute that the avant-garde has arrived at 'abstract' or 'nonobjective' art -- and poetry, too. The avant-garde poet or artist tries in effect to imitate God by creating something valid solely on its own terms, in the way nature itself is valid, in the way a landscape -- not its picture -- is aesthetically valid; something given, increate, independent of meanings, similars or originals," he explains. Greenberg was the first to define avant-garde (and kitsch) with social and historical context, though he would not be the last. With an ever-evolving definition, avant-garde's only consistency is its inconsistency.

OCMA has been programming exhibitions on boundary-pushing artwork for decades. In 2007, they produced an exhibit called "Birth of the Cool: California Art, Design and Culture at Midcentury," which focused heavily on the "Cool School" artists and the rise in popularity of edgy modern art in Southern California art scenes. However, in 1976 they also approached the topic of the Ferus Gallery and its avant-garde modernists in "The Last Time I Saw Ferus" at OCMA (then the Newport Harbor Art Museum).

Christopher Knight noted the Ferus Gallery as being "the first professional space in L.A. to be principally devoted to the postwar California avant-garde," he stated in an article from the Los Angeles Times in 2008, "...the gallery introduced the work of major L.A. artists."

This gallery was the only institution at the time to give attention to this kind of art and these kind of artists, but it wasn't before long that the larger L.A. scene and other art scenes across the country took note of these rebellious and curious artists as well. California's leading moment in art history was this era in art--a straddling time period that played with modernism, messed with new wave ideas on politics and consumerism, and dove deep into the conceptual backbone of artistic expression as a whole.

At the same time as many artists like Ed Kienholz, Ed Ruscha and Robert Irwin (among others) developed works in a minimalist, light and space heyday, artist Tony DeLap was making a parallel shift to fetish finish in Northern California, just before moving down south to Orange County.

"Like his fellow Californians," art critic Peter Frank wrote in a 2007 article for Art Ltd. Magazine, "DeLap grew up in and inhabits an environment in which materials, not ideas, are most readily at hand--and, ironically enough, illusions, not objects, are the result."

DeLap's work is known as part of the fetish finish era of minimalist art, and came to be a part of the SoCal art scene in 1965. During the 1950s and 1960s, DeLap practiced freelance graphic design while applying his talents at painting and sculptures. In fact, it was during his time as a freelancer, that he started making portable sculpture, and focusing on the temporal, exploring the notion that the idea that was more important than the object. DeLap's particular spin on that notion was to push the illusion more than the idea, over physical object.

DeLap has been featured in numerous solo and group exhibitions, and he enjoyed an extensive retrospective at OCMA in late 2000 to early 2001. He was also included in "Best Kept Secret: UCI the Development of Contemporary Art in Southern California, 1964-1971" at Laguna Art Museum from October 2011 to January 2012 and had a large retrospective exhibition at Oceanside Museum of Art last year entitled "TONY DELAP: SELECTIONS FROM 50 YEARS."

Peter Frank pinpoints DeLap's momentum and specific draw through the minimalist vantage point as helping to shape the rhetoric of minimalist art through his subtle illusion and creativity through finish and form. "DeLap's perceptualism...allows no truth but rather (as Stephen Colbert might say) an optical truthiness. In providing the eye a fun house ride of subtly shifted planes, suddenly disappearing supports, and transformed shapes, DeLap's tweaking deflates the pretensions of Abstract Expressionism and the rhetoric of Minimalism," he wrote in the same article from Art Ltd. Magazine in 2007.

In the exhibition catalog, The Avant-Garde Collection, Cameron states that "there is no longer an avant-garde today, but there might be multiple avant-gardes operating side by side, each one disrupting the accepted parameters of art-making just enough to cause a slight tremor, a shudder in the status quo..." The exhibition takes an insightful look at what avant-garde means in a larger context our art history, from the earliest years of California art history to our larger art scene now, with a thoughtful and inquisitive eye.

Dig this story? Sign up for our newsletter to get unique arts & culture stories and videos from across Southern California in your inbox. Also, follow Artbound on Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube.

Top Image: Eraser by Vija Celmins, 1967