The Art of the Rope: How This Charro Completo is Preserving Trick Roping in the United States

San Francisco. Under hot stage lights and his wide-brim embroidered sombrero, dressed in traje de charro — a sky blue shirt fastened with a big royal blue silk bow, matching fitted pants and leather suede chaps — Esteban Escobedo stands center stage in the Davies Symphony Hall.

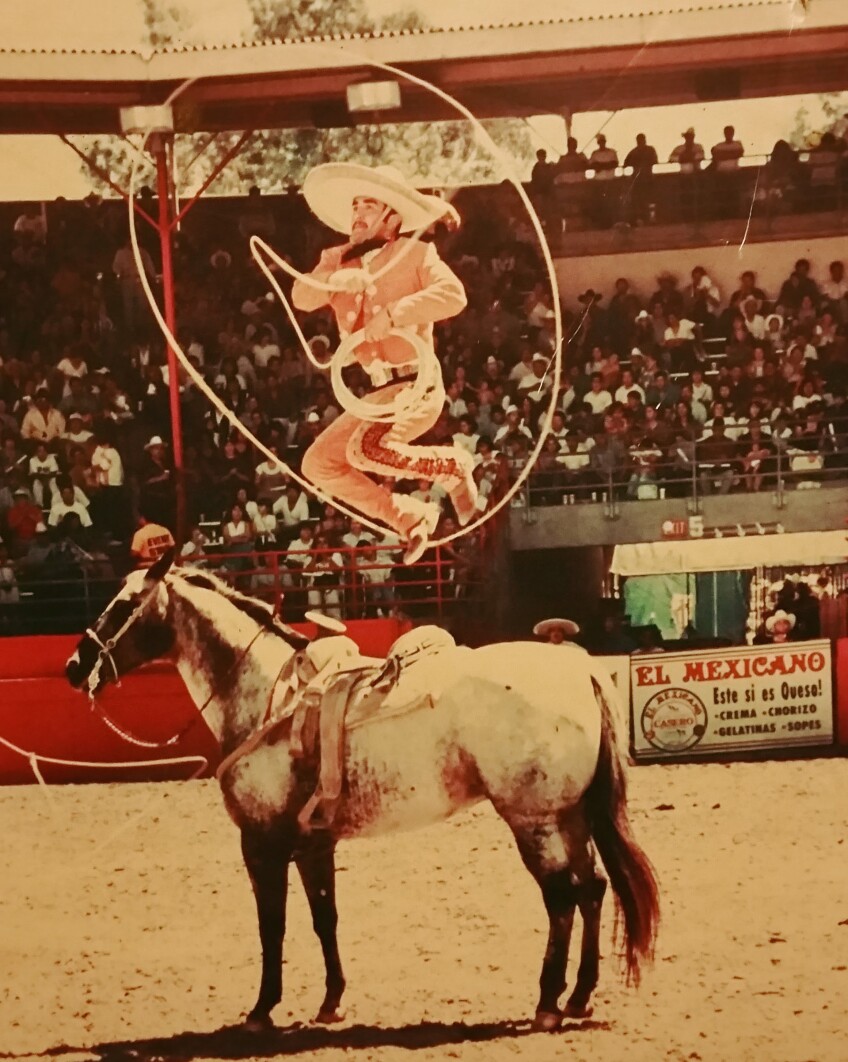

Mariachi trumpets blare. Vihuelas strum. Guitarrón pluck away at "Mi Tierra Mexicana." Escobedo grips a coiled riata (lasso) in his left hand and positions the loop with his right. With control and rhythm, he casts his rope into the air. The loop hovers above his head, a halo suspended for a moment, before he sends it twirling down around his body, then over and around himself — skipping in and out, as the rope circles.

Escobedo is one of only a handful of professional floreadores — Mexican trick ropers — in the United States, and one of a few instructors of the technical expression performing floreo de reata (also known as floreo de soga "making flowers with a rope"), an art form in itself and one of Mexico's longest standing traditions.

It's part of the larger tradition of charrería, Mexico's national sport with origins in Spain's Moorish past, where skills and horsemanship in the nine suertes (events) are defined by a unique rating of riding, roping and attire, the team with the most points at the end wins.

Floreos are carried out in three of the nine suertes. Piales demonstrate a charro's skill with the riata as they rope the hind legs of a mare running full speed and bring it to a stop. La terna en el ruedo is where a team of three work together to lasso a bull from the head and hind legs to bring it down to the ground (adapted as team roping in the American rodeo circuit). Then manganas a pie y caballo, where a charro performs elaborate shapes and tricks with the rope before tying a horse by its two front legs.

Escobedo, a second-generation charro, traces his trajectory in the sport to the Pico Rivera Sports Arena, Southern California's cultural institution for charrería, where his father, Manuel Escobedo, was the charreada organizer for the sports arena from 1984 to 2002. "I was there every day after school and on weekends," he says, calling the arena his playground growing up. "It was a way of life, instilled in me since I was a little kid."

The 44-year-old's proficiency in all nine suertes (events) and dexterity as a rope artist on and off the horse classify him as a charro completo (complete charro), a distinction not all charros hold.

Skillful roping is a discipline deeply rooted in the values and traditions of rural Mexico that came to define the sport. The combining of horseback herding with the use of the riata (rope) to manage large animals — the most useful tool of the vaqueros that were highly efficient in handling it — results in what we know today as "cowboying."

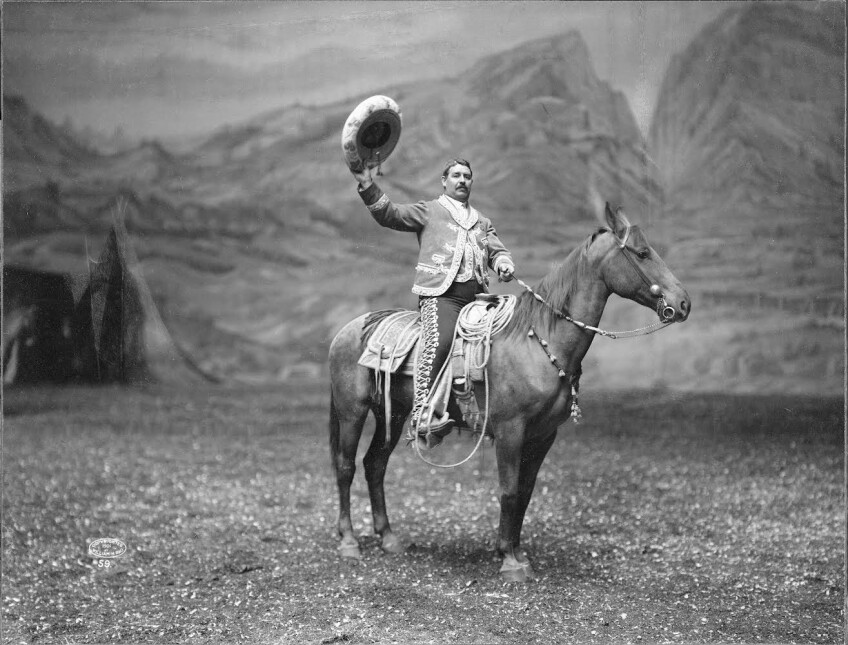

Trick roping (and trick riding) was very much a part of early rodeos in the US largely due to Vicente Oropeza (1858-1923), a pioneer innovator of charrería. He introduced banderillando a caballo (a form of bullfighting) and trick and fancy roping to audiences in the United States and Europe. Born in Puebla, Mexico, he became one of Mexico's greatest transnational performers.

Nathan Bender, reference assistant for the Buffalo Bill Center of the West McCracken Research Library, says Oropeza, was the top roper of the Mexican performers for the Buffalo Bill's Wild West and worked for the show from 1893 to 1907.

Appearing on stages, the "champion Lasso thrower and bull fighter of the world," as one newspaper called him, donning his traje de charro for Buffalo Bill's Wild West, visited five continents, and taught American cowboys trick roping. In an official souvenir from Buffalo Bill's Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World from 1896, Colonel Cody, has Oropeza listed under staff as "Chief of Mexicans."

Will Rogers noted that "no other roper had such accuracy and style as Vicente Oropeza."

According to Michael Grauer, McCasland Chair of Cowboy Culture/Curator of Cowboy Collections and Western Art for the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, Vicente Oropeza was inducted into the National Rodeo Hall of Fame at the National Cowboy Museum in 1975 because of his being a world champion and because of his impact on the history of rodeo. "Señor Oropeza brought the long history of Mexican vaquero to the world through not only his immense skills on the back of a horse, but also through his mastery of the rope. U.S. and European audiences were simply astounded by what Señor Oropeza and his 'Mexican troupe' could do," Grauer says.

For Escobedo and many other charros, the use of the rope in charrería is passed down from generation to generation but unlike many of his fellow teammates, he faced unique challenges being left-handed.

His floreo teachers didn't even know where to start, "they would look at me as if they were looking in the mirror," he says with a chuckle. As a result, Escobedo was oftentimes pushed off to the side. "At first it was frustrating but I started watching videos and watching the charros when they would practice. I kept switching my hands back and forth until I figured it out on my own. Now, any new tricks I learn, I have to do it left-handed first to teach my mind to do it with my right."

By age eight, Escobedo was performing professionally and touring with Mexican ranchera legend Antonio Aguilar as part of the trick roping team, Los Hermanos Escamilla. He performed with the Escamilla brothers for two years and then moved on to perform floreo as a solo artist for Aguilar's shows until 2007.

Escobedo adds that his father, a skilled charro in his own right, joined Antonio Aguilar's act in 1969 performing jinete de yegua (mare riding) y toro (bull riding) and the paso de la muerte (the pass of death), which consists of the charro leaping from his running horse to the back of an unsaddled and unbridled wild mare and then riding the wild mare to a halt with only the mane to cling to. "In the late '80s my father became the show manager in charge of the rodeo crew, taking care of the horses, their training and transportation," says Escobedo, who took over the role as show manager in 1999 on account of his dad having to manage Vicente Fernandez's horse show that year.

For the past 36 years, Escobedo — who also works for the State of California at the Animal Health Branch of the California Department of Food and Agriculture and is the Public Relations Director and Animal Welfare Commissioner for the Federación Mexicana de Charrería en California (Mexican Federation of Charros in California) — has performed floreo with his riata (rope) in various competitions, community centers, universities, cultural events, circuses and with prominent musicians across Southern California and the United States.

Despite his busy schedule, Escobedo still finds time to perform as a floreoador with professional folk and dance company, Ballet Folklórico de Los Ángeles and teach floreo at Thee Academy, a folklorico and mariachi performing arts school in Bell Gardens. He sees it as an opportunity to preserve his culture and advance floreo beyond the lienzo (arena), "I want to get more people involved so it doesn't die out with us," he says. "Unfortunately, most charros are just looking to compete and are not interested in performing floreo outside of charrería as an extracurricular art form."

"It's hard to find floreadores, they're rare," says Kareli Montoya, founder of Ballet Folklórico de Los Ángeles and Thee Academy. "To find one that will perform on stage and is willing to travel with you is very uncommon."

Escobedo currently teaches three classes at the academy, a floreo class consisting of eight students with ages ranging from 11 to 38, a virtual floreo class through Zoom and an escaramuzitas-charritos class (a simplified form of escaramuza and charrería intended as an introduction for children four to eight) made up of eight girls and six boys. Although everyone has a different reason for wanting to learn floreo, Escobedo says he finds himself teaching more and more students that don't come from the sport.

17-year-old Matthew Yales is one of those students.

Yales, who is autistic, has been with Thee Academy for three years. Yale's mother, Jennifer said like some people on the spectrum, keenly interested in specific subjects, Matthew has always been fascinated with Mexican culture — specifically mariachi. Matthew started at the academy taking guitarrón lessons, then asked to add floreo to his curiculum after seeing Escobedo perform and most recently began folklórico dancing. He goes three times a week and practices for multiple hours.

"This is his life. I have extreme gratitude for the art, Esteban and the whole Academy for being so accepting and welcoming," she says. "They're always reassuring and say, 'Just tell him to keep practicing and he'll get it' — and he's getting it."

She added, "They don't let him off the hook because he has a disability. They have expectations of him and it has made him a better person."

Yales recently had his first full performance showcasing floreo, dancing and playing guitarrón unassisted. "I'm very proud of him, he became a different person on stage," says Escobedo.

Escobedo is also excited to see young girls and women engaging with floreo. Traditionally male-dominated, he aims to change this stereotype and empower anyone who is willing to learn, to join.

Sayuri Johnson, a professional dancer with Ballet Folklórico de Los Ángeles, says she wasn't interested in floreo until she met Escobedo. "I just love watching him perform. If you've seen him it's something out of the norm, all the tricks he does with the rope, I found them so amazing," she says. "I saw the passion in what he does and I wanted to be part of it."

Johnson went into learning floreo casually but the more tricks Escobedo taught her the more she wanted to continue pursuing it. "He eventually bought me a rope and he was like, 'I think you should learn, you're going to be great.'" Since then, Johnson proudly joins Escobedo on stage performing a trick where he kneels down and hands her the rope, she continues the loop and hands it back off and finishes her dance. "I really hope to be as good as him one day."

Representing our culture in the most spectacular way possible and being able to get that opportunity through this one skill is priceless.Esteban Escobedo

On a recent Friday, Escobedo is readying to perform a pasada. He sweeps the riata (lasso) across the stage in unison with the emotive violins. Twirling the rope from left to right, Escobedo seamlessly slips in between the loops to jump in perfect time — a dizzying display of fluid movements working harmoniously with his body. Completing the finale, he removes his hat and finishes with a bow to a raucous applause flecked with ovations.

Afterward Escobedo is beaming. It's Mexican Independence Day.

"I never imagined being able to perform floreo at a symphony hall," he says, wiping the sweat above his brow. "Representing our culture in the most spectacular way possible and being able to get that opportunity through this one skill is priceless."

Scroll down to see more photos of Esteban Escobedo teaching youth the art of trick roping.