Swimming Pools and Movie Stars: A History of the World's First Motel

Their signs shine like beacons in the dark, bright with the promise of hot showers, cable TV and air-conditioned rooms.

For decades, motels — sprawling complexes complete with parking lots and swimming pools — have served as a welcome oasis for weary travelers navigating the American West. But while those neon-lit lodges now seem ubiquitous, as much a part of the landscape as tumbleweeds and shredded tires, they’re a relatively recent addition.

Roughly 90 years ago, San Luis Obispo saw the opening of the first motel in the world. The brainchild of Pasadena architect and inventor Arthur S. Heineman, the Milestone Mo-Tel — later renamed the Motel Inn — combined affordability and convenience with all the comforts of home.

“The Motel Inn is one of San Luis Obispo's most iconic landmarks — it figures largely in so many people's memories of the town, for both locals and visitors,” said Eva Ulz, executive director of the History Center of San Luis Obispo County.

That storied past was the focus of the exhibition “What of the Night: Inventing the Motel Inn,” which recently wrapped up a six-month run at the History Center. Presented in collaboration with the Bennett-Loomis Archives, it featured rarely seen photos and memorabilia collected by Paso Robles resident Joseph P. O’Keefe, including ashtrays, dishes, chairs and room keys.

“We wanted to highlight the fascinating history of how the country's original motel was conceived and built right here in San Luis Obispo, and to capture stories of the hospitality that has been enjoyed there over the decades,” Ulz explained.

Before the Motel Inn opened its doors on Dec. 12, 1925, lodging options for American motorists were limited. There were hotels, of course, but those could be expensive, fusty and far away from garages and roadways. Alternatively, travelers rented rooms in tourist homes, pitched tents at primitive auto camps or simply slept in their cars.

Such was the puzzle that confronted Arthur Heineman and his brother Albert, whose work at the architecture firm Heineman and Heineman ranged from residential buildings such as the 1910 Parsons House in Pasadena to commercial projects including Bernstein’s Fish Grotto in San Francisco and the Pig n’ Whistle chain of restaurants and candy stores. They also designed art exhibits for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, held in San Francisco in 1915.

“They worked on the whole scale of the economic hierarchy. They did things for the very rich and they did things for the ordinary person,” said Ann Scheid, curator of USC's Greene and Greene Archives at the Huntington Library, a program of the Gamble House. (The archives acquired a collection of drawings, scrapbooks and other items belonging to the Heineman brothers in 1971.)

“They were active in city building,” Scheid continued. “And they were open to new ideas. They were quite innovative.”

According to his great-grandson, San Diego digital marketer Norman McPhail, Arthur Heineman was one of the first people in Pasadena to own a car. “He was very in love with the car,” McPhail said, and recognized how it was revolutionizing the way people traveled.

McPhail said his ancestor came up with the idea for the first “mo-tel” — Heineman coined the term by combining the words “motor” and “hotel” — while driving to and from the Bay Area, then a two-day journey. “He said, ‘I wish there was somewhere to stay. ...Why don’t we put something here where people can stay along the road for just a few hours, then pack up and leave?’” McPhail said.

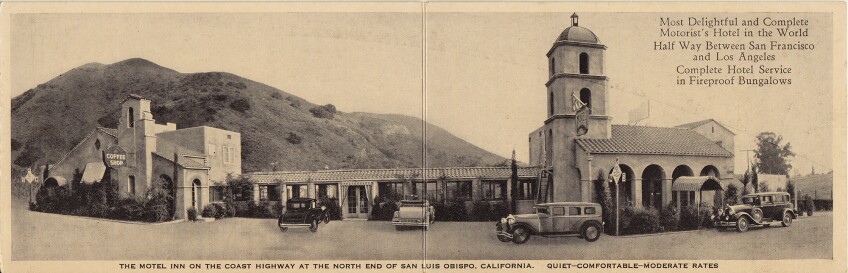

As a location, Heineman and his partners in the Milestone Interstate Corporation picked San Luis Obispo, located halfway between Los Angeles and San Francisco. A site on the north end of Monterey Street backed by San Luis Obispo Creek and the surrounding hills provided easy access to Highway 101 and the Cuesta Grade, the steep passage that bisects San Luis Obispo County into north and south.

One of the Heinemans’ previous designs provided the model for the Milestone Mo-Tel, which cost $80,000 to build: Pasadena’s Bowen Court, a bungalow court completed in 1912.

Now all that remained was to sell the American public on the concept. Toward that purpose, the Milestone Interstate Corp. published a brochure, “The Milestone Marks the End of a Perfect Day,” in 1925.

“Every touring motorist, particularly in California, knows that stop-over accommodations for himself and his family... along main highways are far below actual requirements,” it stated. “But with the advent of the new and original and wonderful MILESTONE MOTEL plan, the motor tourist may start out with his happy family or friends or alone, and enjoy not only the scenic beauties of the open road, but all the comforts of his own home, while away from home.”

Contemporary media accounts echoed the same breathless enthusiasm. “The motel plan eliminates a long walk through dark streets in a strange town between a garage and a hotel,” a 1926 Los Angeles Times article explained. “The motorist’s car is where he is, ready for an early morning start.”

“A traveler arriving at night, or at any other time, need not climb out of his car and go into the office to register,” added a 1925 article in the San Luis Obispo Daily Telegram. “Instead, the man in charge comes out to the car and one may register without leaving the car at all.” An escort then showed the grateful guest to his room, which cost $1.25 a night.

Visually, the Milestone Mo-tel, which could accommodate 100 guests, took its cues from California history. “The whole series of buildings making up the motel breathes an atmosphere of the old Spanish mission, of friendliness, warmth and comfort,” the Daily Telegram article gushed.

Topped with a copper-roofed bell tower modeled after Mission Santa Barbara, the office/lobby building featured a large fireplace and a copper desk “bound with strips of wrought iron like a Spanish chest,” the Daily Telegram article noted. A ramada, or, windowed corridor, connected it to the dining room.

In the back were 15 single-story bungalows built from flame-resistant gypsum blocks covered in chicken wire and coated with stucco to assuage travelers’ fears that the motel would befall the same fiery fate as San Luis Obispo’s Andrews Hotel, which burned down in 1886, or the Ramona Hotel, destroyed in a 1905 blaze. (Ironically, a gas explosion the evening of the opening fatally injured the motel’s new manager and his wife.) Flat roofs, Spanish-style lanterns and sash windows with iron grillwork completed the look.

Inside, the Milestone Interstate Corp. brochure promised, were “real home comforts,” including “restful beds with good springs and quality mattresses,” a “splendidly appointed kitchenette” and a “fully equipped bathroom” with showers and “running hot and cold water.” Other amenities included a service station, servants’ quarters and shared laundry and washrooms. Five of the cozy cottages even boasted attached garages.

Rooms faced a grassy, park-like central courtyard with a palm-covered pergola that eventually made way for a swimming pool. (A miniature golf course and horse stables also came later.) Lush landscaping featuring tropical plants such as bougainvillea, birds of paradise and palm trees gave the property an exotic feel. In the winter, “There’d be a blooming citrus tree in front of every door,” O’Keefe said, releasing a fragrance that lingered in visitors’ memories.

“It was a stopping point for people,” he said, the site of countless first dates, honeymoons, family outings and anniversary trips. “They would come here and have lunch, or stay and make a day out of it.”

Heineman envisioned the Milestone Mo-tel as the first “unit in a series of the most comfortable, economical and hospitable inns that can be found anywhere in the country,” “dedicated primarily to the service of the motoring public,” as the Daily Telegram article put it, stretching from San Diego to Seattle. Much like the missions, each of the visualized 18 motels were to be built to be a day’s journey away from the next.

But the arrival of the Great Depression meant Heineman had difficulty finding backers for the project. Leased to new owners in 1929, the Motel Inn was shuttered a few years later and remained closed until 1938, when it was purchased by Richard Guest.

In 1954, Allen and Marge Calkins bought the motel and ushered the 4.5-acre property into a new era of prosperity. “His personality and her business sense were what made it [a success],” recalled their daughter, Minnesota resident Maggi Calkins Lazaretti, who was 4 years old at the time.

Starting at age 6, “I would get up at six in the morning and run the switchboards and check people in,” Lazaretti recalled, leaving her post only to make coffee and let in the donut delivery man. “I worked every job in that place. I waitressed. I was a salad [bar] girl. I did some cooking. ...I learned how to make the beds, learned how to clean the rooms.”

She also got to know the clientele, which included celebrities such as Clint Eastwood, Lucille Ball and Bob Hope. Newlyweds Joe DiMaggio and Marilyn Monroe lunched at the Motel Inn in 1954, after spending their honeymoon night in Paso Robles.

When Lazaretti was 9, “The cast of ‘Rawhide’ woke me up at two in the morning... banging on my bedroom door,” which stood over the carport, she said. Her father, who was catering their shoot in Paso Robles, convinced them to come back later.

That wasn’t the Motel Inn’s only brush with show business, either. In the 1960s, San Luis Obispo radio station KVEC called the motel home. Scenes for the 1977 action movie “Stunts” were shot there years later.

According to Lazaretti, food was a big draw at the Motel Inn during its mid-century heyday. After enjoying a few drinks at the cocktail lounge, guests would dig into salads doused in housemade dressing — so popular it was sold at the restaurant in jars — and steaks and spare ribs barbecued in an open pit visible from the dining room.

But the beauty of the place also played a part. Lazaretti recalled how her mother, who kept a rose garden and filled one patio with potted orchids, would float gardenias in the swimming pool for weddings. “It was magical,” Lazaretti said.

After her husband’s death, Marge Calkins sold the Motel Inn in 1974 to Stan and Virginia Genest, who passed the property to Milton and Betty Grau two years later. By the time Bob Davis, the owner of the adjacent Apple Farm Inn, acquired the motel in 1991, its restaurant and guest rooms had been shuttered for more than a year.

“They were pretty much in ruins,” recalled O’Keefe, the Apple Farm’s landscape manager. He used one of the bungalows as his office and found that the accommodations, once luxurious, felt cramped.

Still, he was not immune to the Motel Inn’s charms. “I would touch the walls of all the buildings around here... and go, ‘God, there are just so many memories here, so many spirits walking around here. It just needs to be documented. It needs to be captured,’” O’Keefe said.

He made it his mission to save as many “trinkets” from the motel’s past as possible. “Everything that went in the dumpster, I dove in after it and got it,” said O’Keefe, whose collection of Motel Inn memorabilia ranges from smaller items such as matchbooks and restaurant menus to a cast iron sink, a pair of paneled doors and a couple of metal urns used as champagne buckets. “I wanted to salvage as much as I could to share with the next generation, and beyond.”

O’Keefe was fortunate to rescue his treasures when he did. Developers John King and Rob Rossi purchased the Motel Inn for $3.6 million in 2000 and bulldozed most of the remaining structures in 2005, with the exception of the front office, which now serves as office space for Apple Farm employees, and the free-standing restaurant facade.

Now the Motel Inn property is getting a new lease on life.

Together with San Luis Obispo development company CoVelop Inc., King and Rossi plan to build a 55-room hotel and recreational vehicle park. In addition to a 34,500-square-foot inn and 12 Mediterranean-style bungalows, the project. designed by local firm Studio Design Group Architects. will feature 10 Airstream trailers and RV spots. Other features include a restaurant, swimming pool and reflecting pool.

“It’s really trying to capture the feeling of what [the Motel Inn] used to be,” Rossi said of the project, recalling the original motel’s charm while conforming to modern standards for size, safety and comfort.

He hopes to break ground in June, with doors set to open in the fall of 2018.

McPhail is thrilled that his great-grandfather’s legacy lives on in San Luis Obispo.

“What catches my interest is that [the motel] is everywhere you look in the United States now. It’s such a big part of Route 66,” McPhail said, a tribute to Arthur Heineman’s vision. “He created something that was truly unique and still around today.”