Soldadera: The Artist Meets Her Muse

Inspired by Nao Bustamante's exhibition, Soldadera -- the artist's "speculative reenactment" of women's participation on the front lines of The Mexican Revolution -- Artbound is publishing articles about the exhibition's development, historical contexts engaged by this project, and writing inspired by the work. Soldadera was guest curated for the Vincent Price Art Museum by UC Riverside professor Jennifer Doyle.

The soundtrack for "Soldadera," a five-minute looped projection, dominates the gallery for Nao Bustamante's exhibition at the Vincent Price Art Museum: trumpets blare, drums boom. It is the sound of urgency, a call: ¡Ándale!

The film plays across a huge, free-standing screen. Archival photographs documenting the Mexican Revolution flash by, in rapid fire. Battle scenes, executions, trains moving the troops, men on horseback and in trenches, Pancho Villa drinking a glass of buttermilk. Women dressed in bright yellow "fighting costumes" move through other photographs: two soldaderas, arms locked, wheel around each other, dancing in a huge crowd. Another soldadera shoots her pistol in the air at the news that the war is over; a drum thunders each shot. The room gets quiet. A very, very old woman's hands emerge on the screen. She is clapping out a specific beat: clap clap clap. Clap clap clap. Clap clap clap. The sound of her clapping continues over a transition to four 21st-century soldaderas marching toward the viewer, weapons drawn. Layered over a century-old portrait of a battalion of Adelitas, these women are marching toward the camera, toward us. They are marching into the future. Clap clap clap. Clap clap clap. Everything is keyed to the old woman's rhythm.

You can also hear her rhythm if you slip inside Bustamante's installation "Chac-Mool." Built into an old stereoscope viewer, "Chac-Mool" offers a very different experience -- a one-on-one encounter with the last surviving soldadera. To view this work you have to lower yourself and sit down. You have to slip your head into a set of wooden headphones, and peer into the viewer. There, in tiny stereoscopic video, you find a woman, Leandra Becerra Lumbreras, resting in her bed. She taps out this beat on a cookie tin. Her hands drift along her body. She taps -- tap tap tap -- along the length of her legs and moves back to the tin. Tap tap tap.

"Chac-Mool" is intensely peaceful. Its magical soundscape, developed in collaboration with sound artist Kadet Kuhne, creates a gentle holding environment for our encounter with the 127 year-old Lumbreras who, at the time this film was recorded, was not only the last surviving soldadera; she was also the oldest person in the world.

Where "Soldadera" works with the sounds of war, "Chac-Mool" works with the sound of the end of all war. How, the artist asks us, do we listen, and fight, for that?

This question goes to the heart of Bustamante's interest in the soldadera. Many of us are drawn to the gender-rebellion signified by a woman who takes up arms. Our imaginary is peopled by historical and mythological women warriors: Boudica, who, around 60 AD, fought the Romans in what is now England, the Aztec warrior goddess Itzpapalotl with her knife-tipped wings, the illiterate peasant Joan of Arc, who united France and was burned at the stake for daring to speak directly with God, the Amazonian sharpshooters who modified their chests so that they might better draw their bows.

When Bustamante began to study women as they appear in photographs of the Mexican Revolution, she saw something different from this pantheon of warrior women and gender rebels. For the most part, soldaderas are not cross-dressed, they are not on horseback, they do not wielding swords above their heads. The soldadera appears wearing a dress organic to her social position (be she a peasant, or the wife of a merchant). She often appears in a crowd of women -- washing clothes, setting up camp. She might be selling food, or running an errand. The women on the front lines of the Mexican Revolution, in other words, look like ordinary women, doing women's work. How, Bustamante, wondered, can we access her revolution?

Stories about Leandra Becerra Lumbreras popped up on our social media feeds in the fall of 2014, not long after her birthday. On August 31, Leandra Becerra Lumbreras turned 127. News stories about her longevity follow a tried-and-true formula: they list the numbers of her descendents (153), they tell us that her parents were musicians, they explain that although she had five children, she never married. They chalk her long life to a healthy diet, and to never having been burdened with a husband. They mentioned that she liked chocolate, and tortillas. They mention that she made her living doing needlework. And they describe her as the leader of a battalion of Adelitas, and the last living soldier to have fought in the Mexican Revolution. An extraordinary history is folded into an ordinary life. An ordinary life becomes extraordinary for the scope of its history -- for having witnessed the dawn of two centuries, for having moved from a time when cinema was magic to a time when the magic of cinema is folded into a telephone dropped into our pockets. What change did Señorita Leandra not witness?

Learning about Leandra Becerra Lumbreras from a Facebook post is a very 21st-century way of learning about a 19th-century woman. For Bustamante, it was a sign. She had to meet the last soldadera.

When Bustamante returned from her January pilgrimage to Zapopan, Mexico -- where Señorita Leandra lived with her family, until she passed in March 2015 -- the artist's mind had been reset to a specific beat. Clap clap clap. Tap tap tap.

Working with historian Moises Medina and cinematographer Allison Kelley, Bustamante soaked up Lumbreras's presence over two full days, and learned from her family, who were very generous in sharing stories about their matriarch. At one point during their stay, granddaughter Miriam told her grandmother (shouting into her one good-ish ear), "Abuelita, hace tortillas." In response, Señorita Leandra clapped out an insistent rhythm. Clap clap clap. Clap clap clap. In the soldadera's words, she "fought with her tortillas."

"While we were filming," Bustamante explains, "the sound of her tortilla production became the rhythm in my head. I saw the soldaderas in my film marching in unison to her clapping or patting the imagined or rather unseen tortilla. I couldn't see them, but they were there in her ancient hands -- thousands of tortillas becoming perfect rounds."

This is what we see in both "Soldadera" and "Chac-mool:" the last soldadera, clapping, drumming, tapping.

"When she'd clap out that symbolic rhythm of resistance, it was like a puff of love was billowing out from her being," Bustamante says. "Each person on my small crew felt it. Each of us became teary-eyed at one point or another."

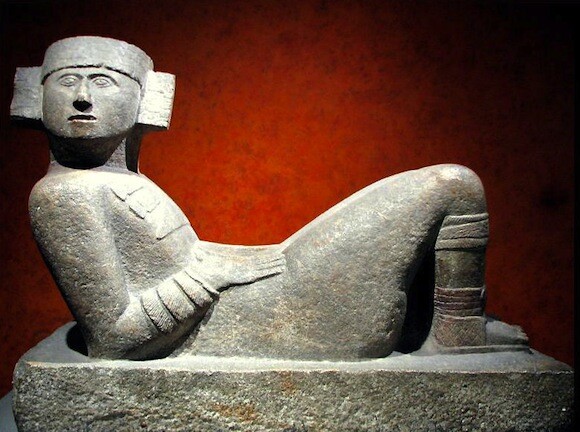

"Chac-Mool" helps us to feel this. The work takes its title from a Meso-American figure positioned on its back, with face turned, head and knees raised. The chac-mool is associated with sacrifice: sculptures of the figure could be used to make an offering, which would be placed on its belly. It has been interpreted as representing a fallen warrior, and as a figure positioned between this world and the next.

Bustamante's approach to the Mexican Revolution has always been sensitive to the question of time -- the work which initiated this project, a dress made of Kevlar ("Tierra y Libertad - Kevlar® 2945"), was imagined as something one might time-travel back to the front lines of the Mexican Revolution. A 21st-century object, projected one hundred years backwards.

But meeting a woman who was there would bring a wholly different perspective to bear upon Bustamante's work with this history. It is one thing, in one's work, to take the present and map it onto a historical situation -- to layer warriors of today over images of warriors of the past. It is another to try to absorb what it means to live that history, to be living with it and to feel that past drift so very far from everyone around you.

Bustamante recalls a moment during one of their filming sessions, in which she felt particularly aware of how special it was to spend time with Lumbreras: "I had spent hours pouring over archival photographs of the Mexican Revolution. And here I was, between takes adjusting the bright red sweat suit of a soldadera. Leandrea had been present during the Mexican Revolution. Her body lived through that war. Here was a woman who had over 46,000 days on this planet," she explains, "here I was, touching her -- this woman who had lived through so much, who had given birth to three sons during the revolution; a women who defended herself and her camp, who had stood in line at the end of the war to claim land for her sons. She was, according to her family, one of the only women given land in recognition for her contributions to the revolution. She had stared down the barrel of many a gun. She had foraged and scraped to feed those around her. This woman sent me time traveling by grabbing my hand and kissing it over and over."

Touching her was like touching the past, future and present all at once. Every touch has the capacity to link us across time -- to connect us to each other's pasts and futures -- but we are rarely aware of the full meaning of this. The clap, the touch, the tap, the kiss; it is all connected in this project.

Describing how she and Lumbreras arrived at the extraordinary scene at the heart of "Chac-Mool," Bustamante recalls, "At the end of the second day, just before going to sleep, she tapped out her rhythm in a very long session. She was on a roll. It was epic poetry. Her keeping a rhythm for over 20 minutes, breaking once in a while to boss someone around in her mind or to speak with her father about her hometown, Tula. It was the end of the day and we were ready to quit, but not Leandra, her performance was distinct and purposeful and we could not look away."

Read more about Nao Bustamante's "Soldadera" project:

Nao Bustamante's Soldaderas, Real and Imagined

Nao Bustamante's exhibition "Soldadera" is a "speculative reenactment" of women's participation in The Mexican Revolution.

Searching for Soldaderas: The Women of the Mexican Revolution in Photographs

What can portraits tell us about soldaderas? Nao Bustamante draws from UC Riverside's archival holdings of photographs of the Mexican Revolution to investigate further.

Soldadera: The Unraveling of a Kevlar Dress

Made out of bulletproof Kevlar, Nao Bustamante's re-imagined Soldadera dresses protect the female body against violence.

My Love Affairs with Soldaderas

From calendars to corridos, the image of the Soldadera lives strong in popular culture. Nao Bustamante's new artwork re-imagines dresses of female soldiers.

Soldadera: The Tiny Things They Carried

Leandra Becerra Lumbreras was the last known survivor of the Mexican Revolution. Artist Nao Bustamante and a small crew made a trip to Zapopan, Mexico to meet her.

Dig this story? Sign up for our newsletter to get unique arts & culture stories and videos from across Southern California in your inbox. Also, follow Artbound on Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube.