Sergio O'Cadiz and the Forgotten Artists of Color in Orange County

Before Little Saigon in Orange County became the largest Vietnamese population in the U.S. (1975), the annual O.C. Black History Parade took to the streets (1980), and the Santora in Santa Ana's Artists' Village was known as the city's Museum of Latin American Art (1990s), J. Sergio O'Cadiz Moctezuma started to incorporate standalone art pieces in Southern California. He contributed to the Orange County arts landscape for over 50 years, yet most of his public work has either been whitewashed or destroyed. The most recent being the mural on Raitt Street that was painted over in 2019.

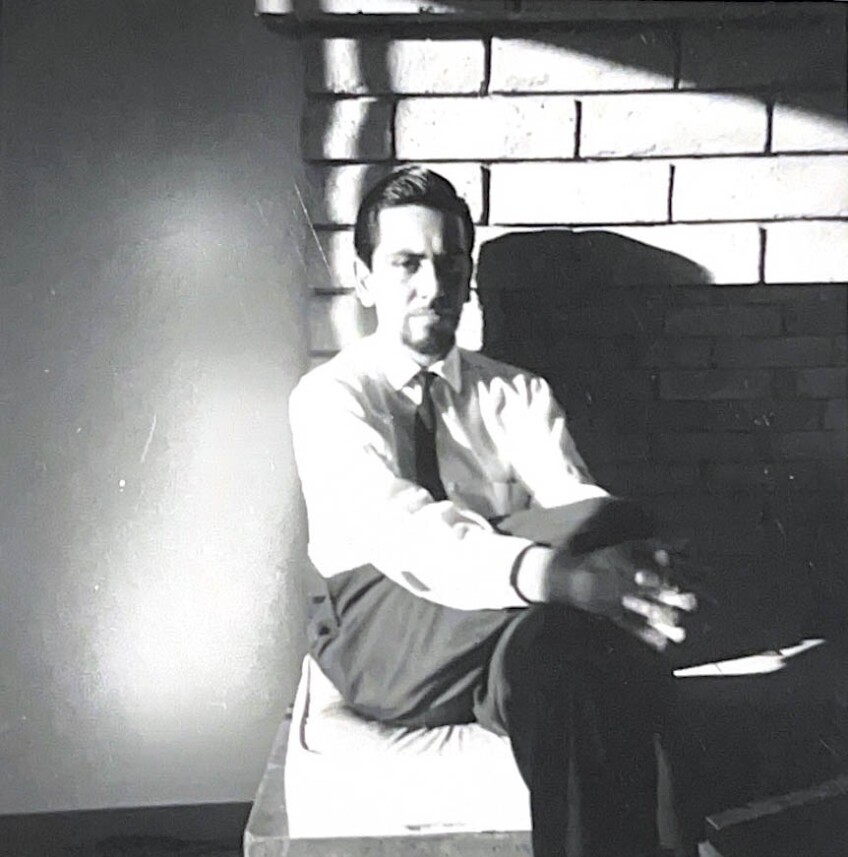

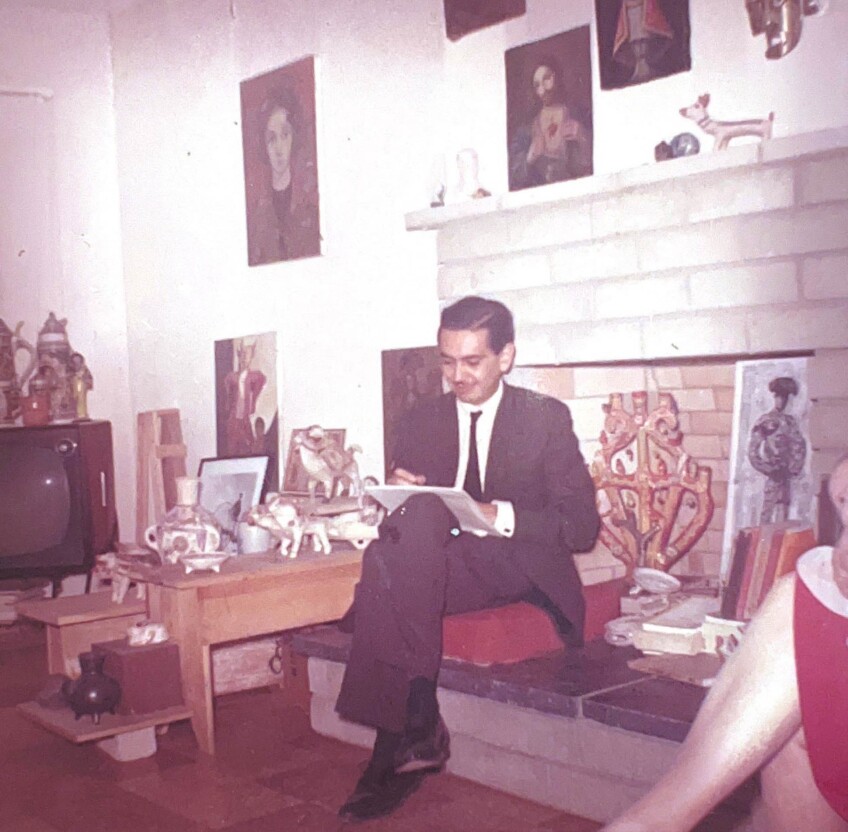

Very few in Orange County know about O'Cadiz's quintessential beginning and his various interdisciplinary art pieces in local art history. After attending the Universidad Nacional Anutónoma de México (UNAM), studying with Diego Rivera, and designing buildings in the country's capital, he was hired by legendary architect William Blurock and moved to Orange County in 1962. O'Cadiz was quickly accepted into the region's bohemian artists' circles and went on to contribute various public pieces in different settings — "Library Mural" at Cypress College (1967), a concrete mural for Santa Ana City Hall (1972), "The History of the Chicano" mural at Santa Ana College's Nealy Library (1974) and he even worked as a set designer for the South Coast Repertory at times. However, just like there's a link between U.S. history and ethnic cleansing in history books, there exists a similar link between the acknowledgement of a culture's experienced reality and its representation in the Orange County art scene. O'Cadiz's 625-foot-long "Colonia Juarez" mural in Fountain Valley was his largest and most controversial public art piece. It was a community initiative, painted between 1974-76 and destroyed in 2001. O'Cadiz died of a heart attack in his art studio in 2002.

The "Colonia Juarez" mural depicted a wide span of Mexican American history, including the battle of Cinco de Mayo, immigrants coming to Orange County and police dragging a Brown man into a squad car. The evocative images motivated local protests by the police department and conservative residents. Eventually the mural was vandalized and consequently lost funding, which meant O'Cadiz could not protect it from further deterioration. Over the decades, the demographics of Colonia Juarez changed and the mural was no longer considered culturally relevant by the new neighbors. The mural was protested once again, this time the city bulldozed the wall claiming it was a danger to the residents.

Since O'Cadiz's passing, Dr. Maria del Pilar O'Cadiz has strived to gain recognition for her father's work. In 2011-2012 she curated a series of thematic exhibitions in Santa Ana and provided access to her father's collection to curator Janet Owen Driggs who presented it as part of the SUR:biennial at Cypress College exhibition in 2019. Both presentations explored O'Cadiz's innovative processes for sculpting and coloring poured concrete, and included paintings, drawings, and public artworks that demonstrated his boundary-crossing ingenuity.

"My father was not about hustling a buck, he understood the complexities of these cultural forms of marginalization and he would voice it," said daughter Maria del Pilar O'Cadiz. "Then people would label him the angry Mexican artist. It was a painful theme for him, he never got the recognition he deserved from the O.C. arts scene…and I believe he died out of heartbreak as a result of the destruction of his work."

Communities of color throughout the 1960s until the present are known for challenging white gatekeeping norms and societal issues through public artworks. As noted in the recently published "A People's Guide to Orange County" (University of California Press 2022), white-washing of Chicano murals is a common occurrence in the region. Along with O'Cadiz's Fountain Valley mural, the book cites two other murals: a 200-foot-long piece by Chicano artist Manuel Hernandez Trujillo in the Atwood Barrio adjacent to Placentia and Anaheim (1978) and the "Cultural Self Determination Prevents Youth Incarceration" mural (2005) by members of the California State University, Fullerton's chapter of Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA). MEChA's mural lasted less than a month before it was removed. Hernandez Trujillo's masterpiece was painted over in 2019 but eventually restored after neighborhood residents successfully lobbied the county for restoration funds.

My father was not about hustling a buck, he understood the complexities of these cultural forms of marginalization and he would voice itMaria del Pilar O'Cadiz

In response to being labeled as the "Other," some artists' communities counter the imposed expectations by seeking alternative forms of social practice, like that of O.C. Heritage Council who now leads the O.C. Black History Parade & Unity Festival founded by the late Helen M. Shipp, Sikhlens, which hosts the annual Sikh Arts & Film Festival in Southern California, and the all-year-round arts programming offered by the Vietnamese American Arts & Letters Association (VAALA) — all organizations have existed for over 25 years in the region. Over the decades, when a cultural group attempts to participate in the arts, they are often typecast to their ethnicity leaving minimal opportunities to establish their own style. Or, the work and the artist are simply accepted as commercial art and tokenized to serve a diversity initiative, which is often experienced at local art institutions and university campus galleries. O'Cadiz's experience is no different than what most independent artists of color experience today in Orange County.

O'Cadiz started designing buildings and teaching art classes in Mexico City, but in Orange County he painted scenes of Mexico and worked more in the abstract. Once thrown into corporate America and the local art scene, he faced what many communities of color still face in O.C.-based art spaces. His ethnicity played a huge role in what was expected and not accepted as a non-white artist. When he voiced his concerns or opposition, he was labeled as the angry Brown man, as most outspoken people of color are still being labeled today. Ultimately, this experience altered his potential to build a renowned career and be included in regional art history. Latinx in the art industry who know of his work have come to acknowledge his struggles and triumphs.

"Sergio O'Cadiz's works, particularly the murals, were subject to the aesthetic and political preferences of Orange County's dominant culture," explained local art historian and curator Joseph Daniel Valencia. "His story reminds us that Orange County is a place of richly diverse yet subjugated artists and art histories. Therefore, in my view, the writing — and rewriting — of the historical record has never been more political."

Art politics is no different than societal politics. The perspective in which art is approached is overdetermined by the location. Although plenty can argue that Orange County, which is approximately 60% people of color, has a diverse art scene, what is irrefutable is that it's more of a variety of style and global representation, not necessarily cultivating artists or cultural arts from the region itself. Now, with ethnic studies being a high school requirement in California and critical race theory being questioned nationally, it seems art history from the perspective of communities of color in Orange County can add to history lessons from the 1960s to the present.

[Sergio O'Cadiz's] story reminds us that Orange County is a place of richly diverse yet subjugated artists and art histories. Therefore, in my view, the writing — and rewriting — of the historical record has never been more political.Joseph Daniel Valencia, art historian and curator

Starting with O'Cadiz as the first of this series of essays is not just appropriate but warranted. Most of society assumes artists of color in Orange County derive from grassroots movements and without formal training, therefore less likely to deserve an artist residency or arts administrator position in a professional environment, let alone historical recognition. These imposed stereotypes continue to be a disservice to artists and arts administrators of color across the region, forcing them to relocate or work outside of the area in order to remain financially sustainable and culturally relevant. While most of the art spaces and institutions in Orange County continue to be white-led, accounts like that of J. Sergio O'Cadiz Moctezumaand the various arts leaders of color who are yet to be documented as part of the people's history of O.C. can prove to enrich the economy, politics and history beyond Orange County's arts landscape.