Separate Cinema Archives: A Black Film Time Machine

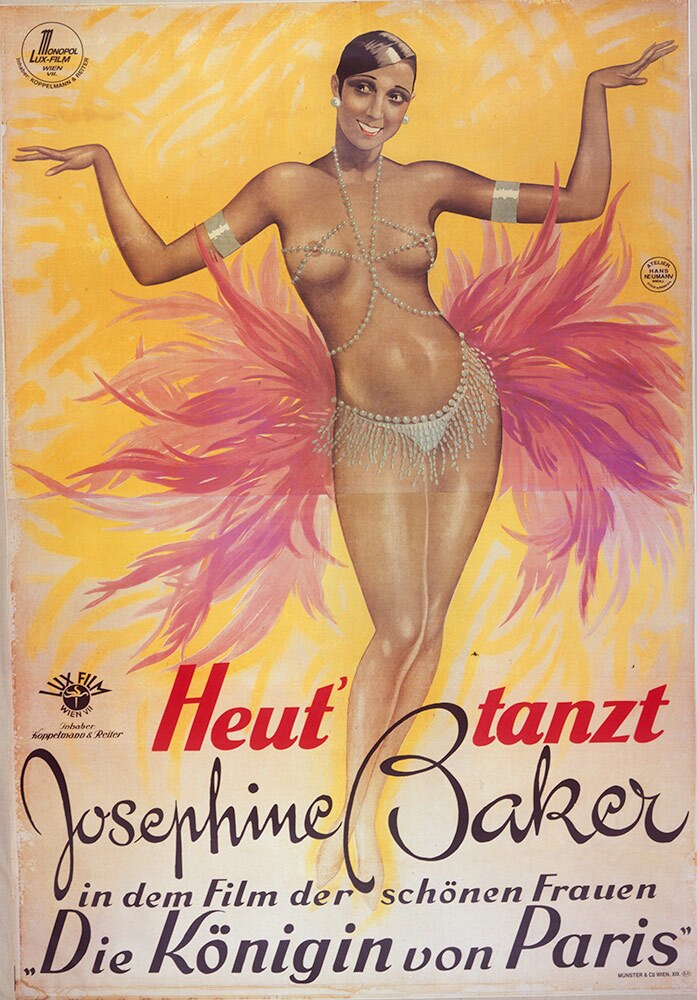

Night has fallen and people are sitting in a dark, crowded movie theater. Smoke from the audience is drifting in the air as the lights dim and people take their seats to enjoy the show. It’s the 1920s, the movie is silent and a scantily clad Josephine Baker dances her heart out in an almost frenetic way. Fast forward three decades to the 1950s, where an equally dazzling Dorothy Dandridge plays Carmen Jones and sings Bizet’s magnum opus.

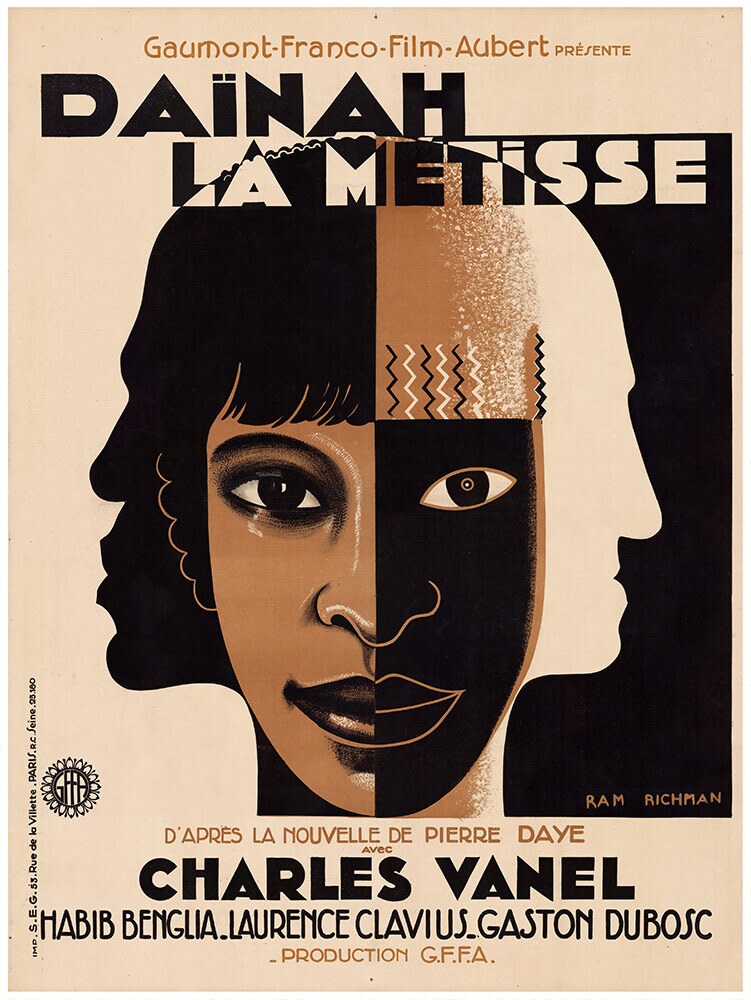

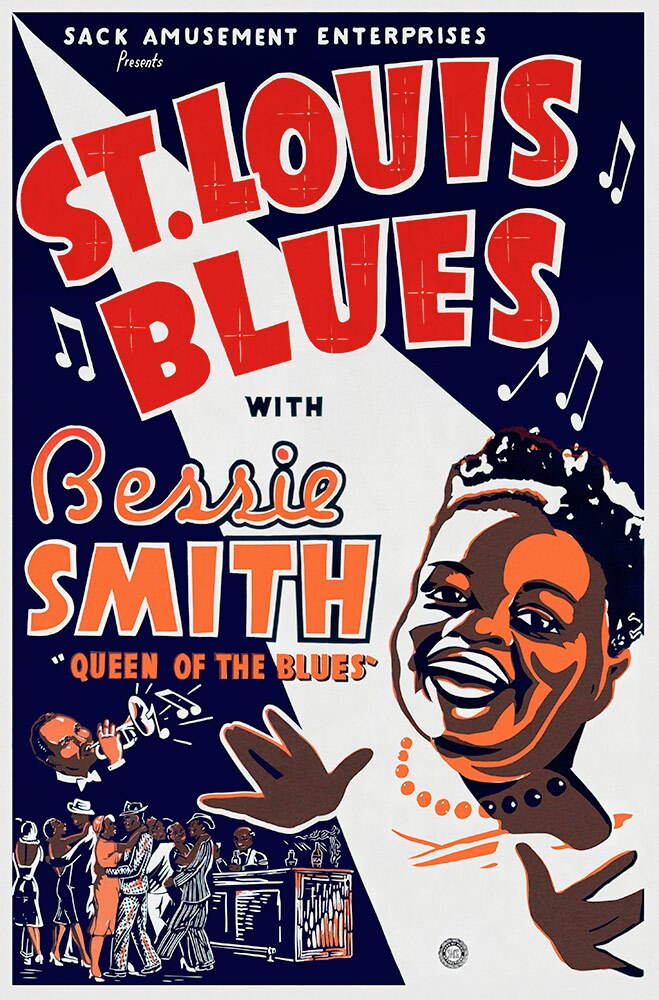

These figures, as well as caricatures of Harlem Renaissance and other icons like Bessie Smith, aren’t in theaters anymore, but thanks to the Separate Cinema archive, they still serve as a time machine transporting viewers back to a segregated world where Black art flourished. Simultaneously, exaggerated racialized stereotypes of Black people and “others” are immortalized as promotional art that was shipped around the world as entertainment. From Carmen Jones to T’Challah of “Black Panther,” the Separate Cinema Archive chronicles African American film imagery and the American legacy of exporting Blackness through art.

The Separate Cinema Archive is the most extensive private collection of African American film memorabilia in the world, documenting over a century of Black contributions to the industry. It boasts 37,000 individual items, mostly movie posters and images used in over 30 countries to promote African American films. It essentially spans the entire history of film starting in 1904 until 2019 and features work by nearly every major African American film star. The work and trajectory of legends like Oscar Micheaux, Dorothy Dandridge, Sidney Poitier and musical legends who crossed genres, such as Duke Ellington and Diana Ross, is plentiful in this collection. For over four decades, the archive’s founder, John Duke Kisch, meticulously built and preserved these relics, ensuring that African American contributions to film remained properly catalogued. Now these items will have a physical home in Los Angeles, at the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, currently under construction in Exposition Park.

The Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, founded by filmmaker George Lucas and his wife, Mellody Hobson, recently acquired the Separate Cinema Archive to add to its permanent collection, in time for the museum’s expected opening in a couple of years.

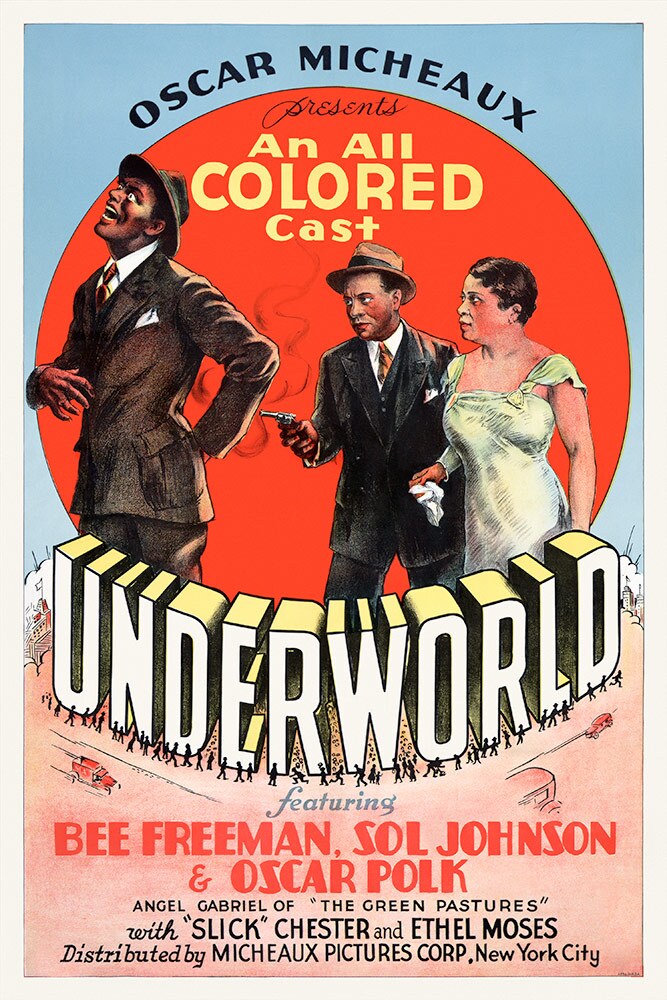

When we talk about the power of film in shaping narratives, we don’t often consider the accompanying artwork that conveys how the story is shaped and sold around the world. The Separate Cinema’s vast collection of authentic movie posters from over 30 countries tells a powerful story not found anywhere else. “The finished film product is an important narrative art form. But also we can highlight and emphasize the way in which films are marketed and sold and the poster itself has interesting work to do, right? I mean it has to distill an entire cinematic narrative into one image,” explains Ryan Linkof, curator of film at the Lucas Museum. The archive’s name, “Separate Cinema,” refers to the popular films featuring all-Black casts made between the 1910s and the late 1940s that were also called “race films.” Though they were independently produced by both Black and white directors, these movies were geared specifically towards African American audiences. A parallel industry of Black films and talent emerged, finding a home in segregated venues across the country, just like many other art forms in the United States at this time. The posters and various marketing materials offer a thorough historical context of how Black stories and Black bodies were consumed and commodified for mainstream consumption.

“The history of posters is one of social movements, it's one of mass communication, it's one of also a collecting tradition for people who couldn't collect artwork. I think this notion of posters and film is tied up in how we socially engage with each other,” says Sandra Jackson-Dumont, director and CEO of the Lucas Museum.

Media imagery shapes how people see and treat each other, and there arereal world consequences, especially for Black people and communities of color, based on how they are presented. Taken separately, many of these posters give viewers snapshots of a particular time, but when gathered together, patterns and stereotypes emerge, as well as contrasts in how certain characters are depicted in different markets.

Get an insider's perspective on the story behind these cinema posters from Ryan Linkof, curator of film at the Lucas Museum.

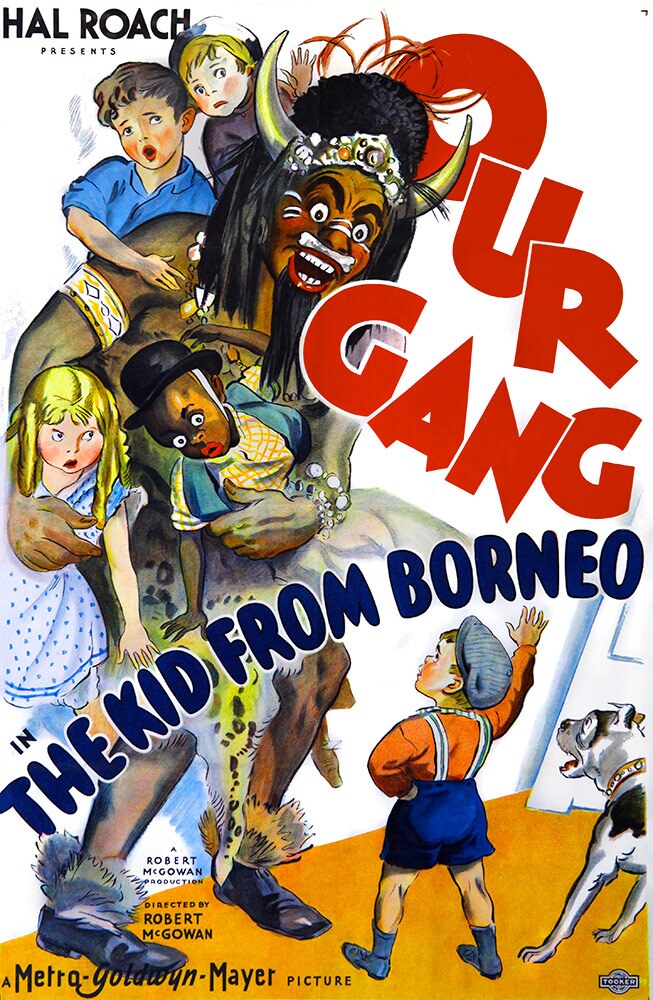

"Here is a poster from the 1933 film, “The Kid from Borneo,” part of the long-running and successful series, “Our Gang,” which was later taken up in TV syndication and known more popularly as “Little Rascals.” The series itself was quite forward-thinking in certain ways. It really placed children of all backgrounds, rich and poor, and Black and White on an equal playing field, which was quite rare. But as you can see, comedy is always trafficking in certain kinds of exaggeration. In this film, an African American man named John Lester Johnson was cast as a man from Borneo. The figure is identified as a cannibal in the film, and there’s an ongoing joke whether or not he’s going to eat the children. So there’s a way in which we’re learning about the contextual nature of comedy that given time and place, certain things register as comedy and they don’t at others. While on the one hand, the archive really does highlight the achievements of African American filmmakers, actors and producers, it also shows the ways in which African Americans are represented in mainstream films in ways that can be quite pernicious, quite problematic. The archive really does show the vast and complex diversity of representation in cinema across the 20th century."

While some of the images depict proud or joyful characters particularly as musicians or entertainers, they also chronicle how racist stereotypes were emphasized through the guise of entertainment. The designs, colors and styles offer layers of information about what was happening in society at the time these images were released; especially depending on who had control over creating these images and the audience they were designed for. The cumulative imagery emphasizes subgenres of different eras, as well as ongoing universal themes. According to Jackson-Dumont, the archive offers infinite subthemes to explore. For example, it illustrates how jazz and sports were deeply embedded in film across decades. Entire movie plots were built around legends like Billie Holiday and Louis Armstrong, for example. It also coalesces work of Black women directors and producers including current phenom Ava DuVernay. The archive also tells a clear story about Black family portrayals in film, and the Blaxploitation era where actors like Pam Grier and Richard Roundtree depicted street justice — and looked fierce doing it.

"Here is a poster from the 1937 film, “Underworld,” produced and distributed by Oscar Micheaux. Micheaux was one of the most important and probably most prominent African American filmmaker of the first half of the 20th century. He really pioneered what became known as race films, films really made by and for African American audiences. “Underworld” comes out in the thick of the Depression, right in the wake of major films such as “Little Ceasar,” and “Scarface” and “The Public Enemy” that were released to kind of appeal to broad audiences with the kind of sinister allure of the city. As you can see in the poster, “An All Colored Cast” is prominently displayed, almost as large as the title itself, which really was meant as a signal for the audiences that this was a film really created with their interests in mind. The entire Separate Cinema archive in some ways comes from this notion, from the idea that there was an almost parallel cinema culture, an industry really developed alongside and in conversation with mainstream Hollywood film."

One of the most notable reflections revealed through the archive is how the same film was marketed in different parts of the world. In particular, Jackson-Dumont mentions the range of depictions ofJosephine Baker as an example. “There are some images of her on posters where she is hyper-sexualized, or kind of a showgirl presentation of her, which we all are very familiar with, but then there's also images of her presented in groups of women that are not necessarily revealing, they're heavily clad and clothed, which I think is also interesting,” she explains. She also notes that other posters depict her as a tap-dancing dandy. Similarly, Linkof said he noticed the differences in how Paul Robeson was depicted in Argentina versus how he was presented in Sweden, and how Dorothy Dandridge in “Carmen Jones” was featured depending on the country. These variations highlight the importance of having these posters archived together to tell a greater story about how African Americans and Blackness were advertised as global stars, and perhaps products.

"What we’re looking at here is an Austrian poster of a German film featuring the American actress and entertainer Josephine Baker. Baker was a well known and well-regarded nightlife entertainer working mainly in Paris. She was born in the United States, discovered as a young woman in New York and swept off to Paris where she became the headline act at the Folies Bergere. This is a short film made about that act by a German filmmaker. And really as you can see stretched across the bottom there, the Queen of Paris, so in some ways she really was a centerpiece of the Paris nightlife. The image itself is quite eye-catching, wearing her spectacular ostrich-feather ensemble, as you can see, baring her breasts. This I think highlights one of the central tensions and one of the most exciting, electric qualities of Josephine Baker. On the one hand, the image commodifies her sexuality quite clearly, but she was also an active agent in that commodification, and in the selling of herself as an erotic and exciting figure. She really used that to become one of the most successful women of color of the time. She understood that she could reach a level of fame and success in her adopted homeland in ways she couldn’t because of certain kinds of discrimination in the United States. She really has endured as an icon and a legend. That’s one of the reasons that the Separate Cinema archive contains a number of posters about her."

“It does call into question the notion of race across the world. And equity, actually. I'm interested in whether or not some of these films saw greater success in certain parts of the world than they saw in others and why that was,” says Jackson-Dumont.

While most of the collection consists of movie posters, it also includes press kits, hand bills and even behind the scenes photographs taken on set. Most notable are the numerous photos shot by Gordon Parks, along with candids of Paul Robeson and Josephine Baker shot by union staff members. This offers a richer understanding and juxtaposition of how Black talent was portrayed for commercial consumption versus how Black artists and community members captured living history from their own lens.

Besides highlighting powerful imagery that shaped perceptions of Blackness over decades, the archive affirms the existence of films that we can no longer view. Linkof notes that many of these movie posters from before 1930, the silent era, are the last vestiges of evidence that these films existed. Because film corrodes easily and art preservation wasn’t valued, and because the African-American market had less resources, much of these movies no longer exist. Entire works of art and pieces of history would be lost forever without the Separate Cinema Archive.

“The kinds of art forms that are the most ubiquitous are not the ones that are dealt with kind of as precious and important, right? I do think it is incumbent upon museums now and in the future to really think about the forms of art that do really kind of represent people's experience and find ways to protect and preserve them. What does that mean for representation when something has vanished to time?” asks Linkof.

While the collection won’t be on view for a couple of years, the acquisition of this collection, alongside the construction of a museum dedicated to narrative art, asks us to consider what constitutes art history and what relics and perspectives are valued. Particularly in an era where everything is digitized and is susceptible to spin, having these tangible pieces of history grounds us in the significant contributions of African Americans in film and the broader art world. It ensures that Black voices and art cannot be erased, while instructing us on the global marketing power of our Black bodies and culture. It is a guidepost for us to be intentional and mindful of the stories we tell, and how ownership and documentation can keep our stories alive for generations that follow.

Top Image: Film poster for "Daïnah la métisse" | from the Separate Cinema Archive; courtesy of the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art