'Sea Sick in Paradise' Tells a Complex Message of Access and Environmentalism

This article was produced in partnership with UCLA's Laboratory for Environmental Narrative Strategies (LENS), an incubator for new research and collaboration on storytelling, communications, and media in the service of environmental conservation and equity.

Do we need to enjoy nature in order to protect it? That’s one of the questions at the heart of a surfing art exhibit in Malibu this summer. The show was co-sponsored by the Laboratory for Environmental Narrative Strategies in the Institute of the Environment and Sustainability at UCLA, a new lab dedicated to environmental storytelling across cultures and media, with the Depart Foundation in Malibu.

When you enter the “Sea Sick in Paradise” exhibit, curated by artist and surfer Amy Yao in a pop-up space in Malibu Village, you might first notice a patch of colors on the wall across the gallery’s central open space. It’s a board wider than it is tall, divided horizontally into a wash of orange-pink above and gently rippled blue below. So you might stand for a moment, in between two oceans, facing Billy Al Bengston’s “Lost at Sea, 6:00PM” with Malibu Beach at your back.

It is one of many views of the ocean in the show, many of them, like Bengston’s, blurred, fuzzed, partial, out of focus. And in most of these images, the viewer is positioned like a surfer: on the beach or in a wave. It’s as if the pieces are meant to show you what it’s like to see the ocean as a surfer, with salt in your eyes. 'Sea Sick in Paradise' suggests that seeing like a surfer could help motivate people to protect the coast, perhaps even more than facts about threats to our oceans, beaches, and surf breaks.

Joel Cesare of the Surfrider Foundation, and a sustainable building advisor for the city of Santa Monica, made this argument in a panel moderated by LENS co-founder Jon Christensen, one of many events taking place around the exhibition this summer. Surfrider, Cesare said, is based on the “very significant connection” that people experience with a place “that provides them joy.” When people enjoy a place deeply, they begin to see it differently, and are ultimately moved to protect it. In Cesare’s words, there is a natural progression from “enjoyment to protection.”

Indeed, this is the story of the Surfrider Foundation itself, which was founded in 1984 by surfers to clean up and protect Surfrider Beach in Malibu. A version of this story is told in the art exhibit as well. In the surf movie “Forbidden Trim,” clips of which are shown in a back room, a military spy casts off his uptight persona during a semi-mystical encounter with surf culture. He experiences the transformative possibility of loving a wave.

Scholars in the environmental humanities argue that communities devoted to environmental protection are built on stories like these. Compelling narratives, often coupled with scientific knowledge, create powerful environmental movements. But not all stories do this work equally well. In the book “The Power of Narrative in Environmental Networks,” Raul Lejano, Mrill Ingram and Helen Ingram emphasize the importance of what they call “plurivocity”: “the ability of a story to be told in differing ways by different narrators.” The beach can and should be a place for such inclusive stories.

In his remarks at the panel, Christensen, who is leading a multidisciplinary research project on “Access for All: A New Generation’s Challenges on the California Coast,” quoted poet T.S. Eliot: “The sea has many voices.”

The story of surfing has not always been a many-voiced one. Surfers have helped open California’s beaches to the public, but they have also made some beaches and surf breaks unwelcoming to outsiders. The show is aware of this tension. It represents and pushes against the exclusionary elements of surf culture. Jeff Ho’s mural “Black & White” looks like it’s written in a sort of code, except for the words “Locals Only.” Other works highlight more inclusive corners of the surf world. Eve Fowler and Mariah Garnett’s documentary “Life is Torture” explores the experiences of lesbian surfers. And Cristine Blanco’s “Sharks” shows three women of color suiting up for surfing. At the panel discussion on “The New Lineup: Surfing, sea-level rise, access, and inclusion in the 21st century,” Blanco spoke of finding her own way into the surfing lineup as a student in college in San Diego, and now introducing other girls to the ocean with Brown Girl Surf, an organization that gives young women in the San Francisco Bay Area, some of whom live just miles from the beach, their first exposure to the surf.

“Sea Sick in Paradise” includes many voices saying many, sometimes contradictory, things. The exhibit as a whole makes the argument that this “plurivocity” is an important feature of the changing culture of the coast. It is also, as Christensen argues, a key to preserving access for all Californians to the coast, and protection of the coastline in an era of climate change. But art is seldom so literal.

Could art’s focus on the beauty of surfing as easily lead to complacency rather than action?

Beauty is certainly on display in many of the fuzzed-out, idealized images of the ocean in the show. In “The Ocean Comes to Us,” by Peter Fend, a video of waves lapping at a beach loops endlessly on a vintage tube TV. In Tin Ojeda’s photograph “FJV Knost,” a surfer is a dark smudge on a hazy gray wave.

Most strikingly, Matthew Lutz-Kinoy’s “Ocean Essays” consists of a huge tube of painted nylon. It sits at the entrance to the exhibit. Walk in and you’re inside a wave, everything blocked out but the ocean’s immediate blue.

In another of the show’s video installations, a surf documentary plays on both sides of a hanging screen. On one side you can sit in a plastic chair and watch as usual. On the other, you’re forced by the tiny room to stand just a few feet from the screen. Standing so close that you can see the film grain in the projection, you realize that seeing something up close is not the same as seeing it clearly.

But then, as if to put an exclamation point on “Sea Sick in Paradise,” in the last image that people are likely to see in the show, a surfer rides through a curl made up of as much plastic trash as water. Zak Noyle’s photographic illustration “Wave of Change” is a beautiful and disturbing complement to the life-size model wave that invites visitors into the tube at the beginning of the show. Instead of cast-off materials (canvas and wood) used to make a beautiful wave, a beautiful wave is compromised by cast-off materials.

The sudden, clear-eyed view of what an unprotected ocean looks like does not displace, but does complicate, the show’s other idyllic ocean views. And an inclusive story — like the story told in “Sea Sick in Paradise” — should be complicated.

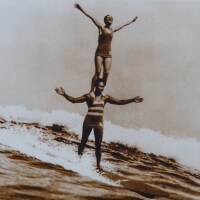

Top Image: B Wandy | Courtesy of Depart Foundation