Samuel Rodney Browne: The Music Teacher Who Broke L.A.'s Color Barrier

On Tuesday, June 9, 1936, a 28-year-old pianist gave a public concert at the Metropolitan School auditorium near downtown Los Angeles. In a program that was equal parts formal recital, community fête and high-wire act, he performed three classical compositions, including Chopin's "Scherzo" and "Barcarolle" by the African-American composer Nathaniel Dett, before accompanying a guest vocalist on a popular "torch" song. He finished out the program by taking tonal requests from the audience that he wrote down on a blackboard. "When completed," previewed The Metropolitan Mirror, the tones would be played "as a waltz, a ballad and a jazz number."1

The pianist's full name was Samuel Rodney Browne, and in three months, after a years-long battle that the California Eagle called "tireless" and the L.A. Sentinel called "tedious" (both in their own way were right) he, along with social studies teachers Hazel Gottschalk Whitaker and Marjorie Bright, would officially break the color barrier for Black teachers in the secondary schools of L.A. Unified. All three were respected members of their community (the Eagle dubbed them "pioneers in secondary education"2) but what distinguished Browne was that he had already integrated his old alma mater, Thomas Jefferson High School by -- in an exquisite twist of racial irony -- slipping in the back door.

Born on April 11, 1908, Browne came of age in a community that increasingly valued music lessons as a cause for social and professional advancement and musicians made up the largest contingent of L.A.'s Black professional class.3 His piano lessons began at age seven with Amelia Lightner, wife of the pastor of the Congregational Church at 43rd and Central,4 before moving on to the conservatories of William T. Wilkins and John Gray, who offered the formal model of music instruction, even emphasizing the term "European System" in their print ads in the California Eagle.5

But Browne also came of age with the rise of jazz, a louche and "primitive" music made by "ear readers" that made his elders curl their noses. He grew up in their neighborhood and walked their siblings home from school when he was a senior at "Jeff." Like them, he bore the "scars" (his words) of hearing his white teachers hurl racial epithets at him and his fellow students, like the third grade teacher who drawled to her class: I'm from the South and I won't take anything from niggers.6 "[Jefferson's faculty] was still mainly white then," Browne recalled. "I remember I had to fight to play Chopin at the commencement exercises. They didn't think much of a black kid doing that kind of thing, no matter how talented he might be. But they let me, and patted themselves on the back about how democratic they were."7

Outside of school, Browne had to accept many of the same jobs as the "jazzbos," and thusly traversed the worlds of serious music and Jim Crow-era entertainment. During his senior year he sang in the choir of jubilee singer Emmanuel Hall for "Hearts of Dixie," an RKO Radio picture that also featured the only filmed performance of blues singer Bessie Smith. "There were pictures that depicted racial themes set in the South, so they wanted Negro choirs to do the singing of the spirituals and the slave songs," Browne later explained. After graduating summa cum laude from USC in 1929, where he reasoned he was one of only six Black students, he joined a Southern-hokum revue called The Alabama Crooners whose act teetered on the edge of minstrelsy. "These were not Alabama people, but that's the way things had to be," Browne remembered. "If you were black and you wanted to sing... you wore the bandannas and overalls... It was a matter of survival. If you said, 'Well I won't do it,' you don't eat because then you don't work."8

Browne's big break would come during the Great Depression, courtesy of President Roosevelt's Civil Works Administration. "My wife-to-to-be was telling me to come home, that the barriers were coming down," he remembered.9 He secured a job teaching night classes at the "Colored YMCA" at East 28th and Central. Fortuitously, also meeting weekly at the YMCA10 were the pooh-bahs of the Los Angeles Forum, a progressive consortium of influential community leaders and business owners who formed back in 1903 to promote equal education and employment opportunities for Afro-Angelenos. The Forum raised finances for the education of Ruth Temple, L.A.'s first African-American doctor of record,11 and they soon took note of the ambitious young scholar teaching night classes just down the hall.

Browne's alma mater still had an all-white faculty despite the fact that by the 1930s its student body was predominantly Black. "From there I thought I would like to teach night school at Jefferson High. So I asked, 'Why can't I teach there too?' I went to see the principal and he said, 'I'll hire you but you'll have to get fifty people to sign up.'" Browne summarily returned with 50-plus signatures from his church choir and congregation and was eventually hired in what amounted to a "soft rollout" as a day-to-day substitute teacher for Jefferson's adult night classes for $166 per month.12 "I thought I was the richest person in Los Angeles," he remembered.

After his "official" hiring in fall 1936, an assistant district superintendent called Browne into his office. "Remember, Brownie," he cautioned, "now that you've got the job, you're going to have to do the work of three white men." According to Browne, once news spread of his hiring, teachers on the all-white faculty immediately asked to be transferred. He knew powerful eyes would be on him to produce, especially after he petitioned the L.A. Board of Education to establish an official curriculum for a jazz band. "I wasn't an activist," Browne would admit. "If I was, I wouldn't have lasted one day. As it was, I was almost fired a couple of times."13

In response to all haters, Browne went into overdrive, conducting the regular Jefferson orchestra as well as the marching band. He showed up at 5 a.m. every morning and left after 6.p.m., taught six periods a day, conducted classes on weekends, and forewent his free periods and lunch hours. "I didn't care about anybody -- or anything else," he later said. "I was motivated to go above and beyond the call of duty. I didn't think about the hours of work because it wasn't really work. I was driven to do it. It was the love of my life."14 He soon discovered a symbiotic relationship with his students, mutual reliance based on mutual need. "He seemed to be hip to the things we were into," remembered drummer Bill Douglass. "The big band swing era was happening and... we were all interested in what was going on and he was capable of teaching us what we wanted to know."15 They soon came to the doorstep of home on 33rd Street near Central for what developed into informal salons. "We would sit on the floor and listen to my phonograph," said Browne. "They would listen to and transcribe things like music played by Jimmie Lunceford and Count Basie. These kids were interested in jazz, you see... that's what they wanted. They also wanted me to play my classical music, so I entertained them with it. They'd say, 'Mr. Browne, play this, play that.' And I would play it... we never neglected the classics."16

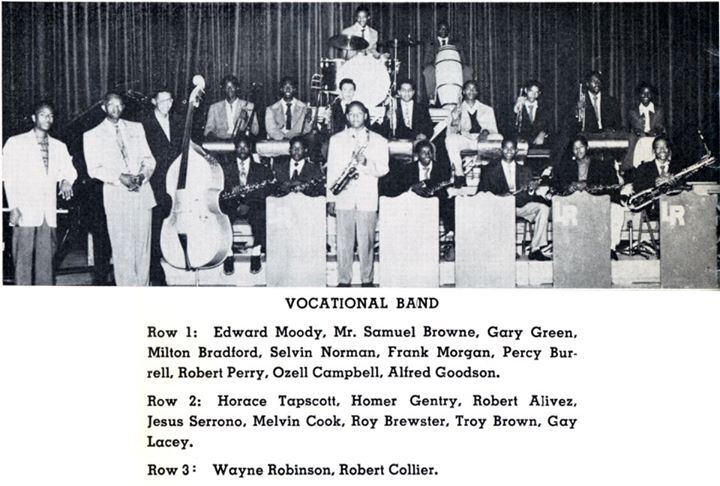

Browne's industriousness had birthed a self-replenishing factory that appealed to multiple generations that bridged the eras of big band to free jazz. He recruited his students like a football scout, traveling to junior high schools in the area to scope budding talent, telling the ones he picked, You're going to play in my orchestra. You're playing second horn. Browne ensured a rigorous education they would not soon forget. As one of Browne's later students explained, "Dr. Browne wasn't intimidating, he was commanding."17 Thin and soft-spoken, he stood spine-straight over six feet tall, impeccably dressed in professorial three-piece suits with pressed pocket handkerchiefs and shoes that gleamed like glass. Bebop saxophonist Frank Morgan compared him to his own heroes: "He was like Charlie Parker or Miles Davis or John Coltrane. He was a demonstrator. He just didn't talk... he played it. He was in the trenches with the students. He played with them every day."18 Browne brought in such local luminaries from the worlds of jazz and art music as William Grant Still, Nat "King" Cole, Lionel Hampton, W.C. Handy, Stan Kenton, Jimmie Lunceford, Shelly Manne, George Shearing and Ethel Waters for recitals and master class seminars. Browne's pupils respectfully dubbed him "Doctor" -- or, if they were daring, "Count" -- and he worked to see that they "were taking care of business" or to track down truants from his classes. He prepared his band to arrange and compose like they were musical shock troops by telling them: "You have to be much better than the guys that go to Hollywood High."

By 1960, Dr. Browne's harmony, counterpoint, music-reading and arranging classes had produced a stunning array of talent over the years. Aside from the aforementioned, there was vocalists Ernie Andrews and O.C. Smith, pianists Lady Will Carr and Horace Tapscott, saxophonists Sonny Criss, Cecil "Big Jay" McNeely, Jackie Kelso, Vernon Slater, Dexter Gordon (whom Browne frequently put in detention just to make him practice his scales), trumpeters Art Farmer, Ernie Royal and Lammar Wright, Jr., drummers Carl Burnett, Chico Hamilton and Lawrence Marable, and violinist Ginger Smock. Browne's small-frame Bungalow 11 evolved into a crucial networking spot during band practices and lunchtime jam sessions; indeed, many of his older pupils who were now working in the clubs and studios would drop by along with recent graduates. Trumpeter Don Cherry got into trouble by cutting classes to be part of this milieu. "All the musicians and music was happening at Jefferson," Cherry said in a 1985 interview. "I got sent to detention school because I was ditching Fremont [High] to go play in the swing band at Jefferson."19

Although Browne was married in 1937 to a supportive wife, Virgel, and fathered a daughter, Lisa, who would graduate from UCLA,20 he remained a strangely solitary figure. "Sometimes I'd go to Jefferson late at night to work," he recalled. "It used to rain... and I would hear the rain falling and watch the trees blowing in the wind. I was all by myself in that bungalow -- all alone. I loved that."21 At these moments, the recurring meetings with school officials who didn't approve of him not eating lunch with the other teachers or bringing in musical luminaries regardless of their race22 faded into background static. In 1979, six years after his retirement and twelve years before his death, at a Jefferson alumni dinner in his honor, a former student spotted Browne sitting against the wall of the Proud Bird restaurant, taking in the proceedings for his benefit from afar. "I hadn't seen him in many, many, many years," Jackie Kelso recalled. "I knew that I was going to have to demonstrate to him in some sort of way my appreciation of what he's done for me and everybody else." Kelso proceeded to fall down at the floor at Browne's feet and kissed his impeccably shined shoes. Dr. Browne merely glanced down upon him: "Jackie. How good to see you."23

Notes:

1 The Metropolitan Mirror, 5/21/36

2 "Mrs. Park of Board is Praised," California Eagle, 9/4/36, p. 1

3 Yarbrough-Cox, "Central Avenue: Its Rise and Fall," p. 14

4 Yarborough-Cox, "Central Avenue: It's Rise and Fall," p. 97

5 Catherine Parsons-Smith, "Making Music in Los Angeles," p. 183

6 William Overend, "A Black Teacher Recalls Another Era," Los Angeles Times, 9/14/79

7 Ibid.

8 Yarborough-Cox, p. 105

9 Overend, p. 12

10 Scott et al, "The City," p. 341

11 Yarbrough-Cox, "The Evolution of Black Music in Los Angeles," in De Graaf, "Seeking El Dorado," p. 252

12 Ibid.

13 Overend, p.13

14 Ibid., p. 107

15 Bryant et al, "Central Ave. Sounds," p. 235

16 Yarborough-Cox, "Central Avenue: Its Rise and Fall," p. 107

17 Carl Burnett, Author Interview, March 2014

18 Ibid.

19 Kelso, "CASOH," p. 92

20 Overend

21 Kelso, "CASOH," p. 92

22 William Overend, L.A. Times, 1979

23 Jackie Kelso, "Central Avenue Sounds Oral History," p. 92