Retro ‘Pee-Chee’ Folders are Re-envisioned to Memorialize Victims of Police Violence

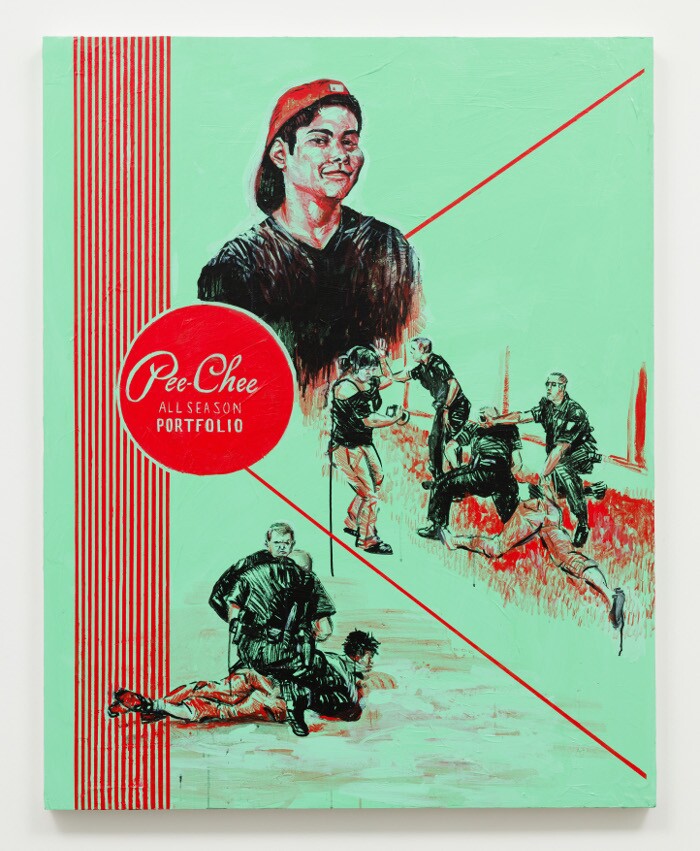

Amidst stacks of paintings inside Partick Martinez's studio is "The Most Violent Week in America," an 8-by-5-foot piece that looks like a giant's school folder splayed cover-side up. Designed to look like the classic Pee-Chee folders that filled school supply aisles and lined desktops for decades, the painting instead focuses on horrific events of one week in July of 2016.

On July 3, 19-year-old Pedro Villanueva was shot and killed by undercover CHP officers in Fullerton who had followed the unarmed teenager and his passenger from a street racing event to a dead-end street. Two days later, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 37-year-old CD vendor Alton Sterling was shot and killed by police officers. The following day in a suburb of St. Paul, Minnesota, Philando Castile, just shy of his 33rd birthday, was shot and killed by police officers during a traffic stop. The next day, Micah Xavier Johnson opened fire on police officers at a Black Lives Matter protest in Dallas.

The week is memorialized in images that reference the illustrations on those old folders. In the top left corner, there's a portrait of Castile. "It's hard to watch that video," says Martinez of the footage that Castile's girlfriend, who, along with their young daughter was in the car at the time of the shooting, had broadcast via Facebook. "I kind of wanted to do him a solid and paint his portrait in the top left." In the top right corner, Villaneuva sits on the bed of a pick-up truck holding a guitar, as he did in a photo that accompanied news reporting of his death. Underneath that, Martinez recreated the image of Sterling shot by an officer. Along the bottom, he painted police scenes from Dallas.

Since early 2015, Martinez has been documenting instances of violence in the U.S., much of it involving police brutality and death at the hands of officers, in Pee-Chee-style paintings. In that time, he has made an estimated 20 such paintings. Some are in the hands of private collectors. Others are at galleries like Charlie James in Los Angeles and Guerrero Gallery in San Francisco. A few are inside his work space at a studio on the border of Los Angeles and Vernon that he shares with other artists.

During a recent visit, the heat inside the work space has grown intense and Martinez has his current work-in-progress set up in a hallway where he can catch a bit of a fan-made breeze. It's turquoise with scenes unfolding in shades of purple and black. Titled "Public School Pee Chee," this one unfolds in a slightly different fashion than others in that it depicts the affects of violence on young people. There's a boy standing with arms outstretched as an adult runs a security wand down his leg. There are young, female basketball players brawling in a bottom corner. Above them "World Star" — the name of a viral video site and a popular chant during fights — is scrawled in Wite-Out. In between the two images, a spring break homework reminder is scribbled in Bic pen.

Martinez, 36, is a prolific artist with a varied body of work that includes paintings, sculpture, neon signs and mixed-media projects. His original Pee-Chee piece took the form of a screen print back in 2005, and portrayed what he calls a "generic version" of his representations of violence. In this piece, cops are seen chasing a person, pushing someone and running with a gun pulled. He showed the work from 2005 through 2007 and then put the idea aside.

A decade after that initial concept, technology had drastically changed how police brutality was reported and distributed. Now, people could use their cell phones to document the acts and upload those photos and videos to sites like YouTube or other social networks. Now, the general population was getting a glimpse of the violent and, sometimes, lethal force that has been used in cities across the country. After the deaths of Eric Garner in New York and Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, Martinez was compelled to revive the Pee-Chee concept. "I had reference now," he explains. And as the news cycle continued to turn out stories of one tragic death after the next, as the Black Lives Matter movement gained steam, Martinez continued to paint. "There was always content," he says.

At times, Martinez has also looked to the past for inspiration. In "Nine Deuce," he recalls the beating of Rodney King and subsequent uprising in Los Angeles, with Lakers shades of purple and gold. In "Vintage Throwback Po-Lice," he pays tribute to Ruben Salazar, the Mexican-American journalist who was killed inside an East Los Angeles bar when he was hit by a tear gas canister on the day of the Chicano Moratorium march in 1970. More often, though, his points of reference are contemporary. For a show at Guerrero Gallery in San Francisco, he painted Alex Nieto and Oscar Grant, whose deaths are tied to the Bay Area. In his most recent completed piece, "Po-Lice Misconduct Misprint 8," he revisits Michael Brown by depicting him in a cap and gown and includes Daniel Harris, a deaf man who was killed by a state trooper in North Carolina last August.

Martinez made folder-style prints of an earlier piece that featured Eric Garner. He distributes the prints to high school and college students. The college kids, he says, immediately understand the work. The high school crowd, on the other hand, doesn't always get it. After all, Pee-Chee folders are now largely vintage ephemera. "It's just a folder to them," he says. Sometimes, students will drop him an email later. Other times, teachers contact him asking for prints to distribute in class. Right now, he's backed up on fulfilling those requests.

Meanwhile, there are canvases prepped and ready to go inside Martinez's space. "I can do a lot of these," Martinez says. "I have blank canvases here, but they'll be filled soon." Those statements come with a hint of sadness in the tone. "If I can do this many paintings of it, it's a problem," he says. "It's an issue."

Some might see Martinez's work as political in nature, but he sees it more as "time-stamping" events. He says, "It's just something to record history and present it in a creative way."

And, it's a way to preserve the memory of those whose lives were cut short. "I want to represent everybody and have their story at least be acknowledged," he says. "That's why I'm doing a lot of them."

Dig this story? Sign up for our newsletter to get unique arts & culture stories and videos from across Southern California in your inbox. Also, follow Artbound on Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube.