'Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898-1971' Reveals the Tenacity of Black Creativity in Film

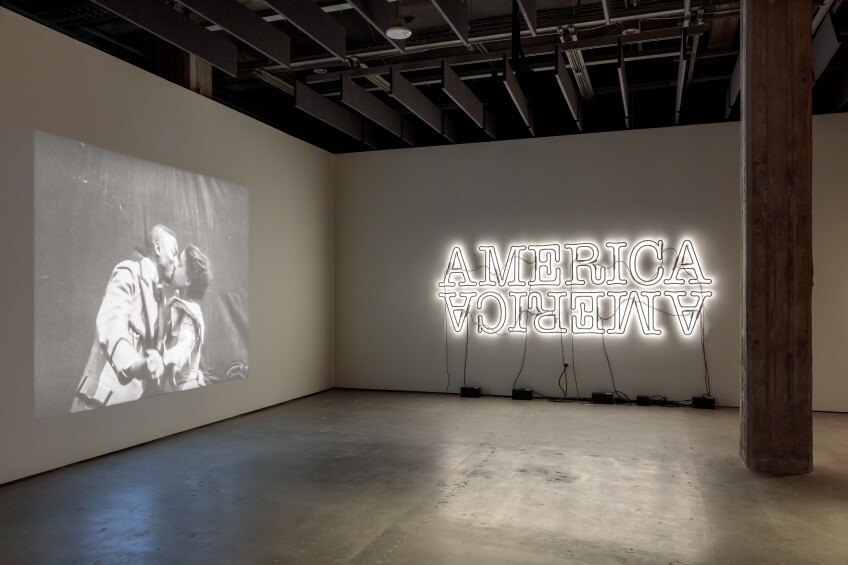

Though less than 30 seconds long, "Something Good — Negro Kiss," a short film directed by William Selig from 1898, casts a hypnotic spell. In the clip, vaudeville performers Gertie Brown and Saint Suttle play lovers lost in the sweetness of their embrace. They flirt, hold hands, laugh and tease one another in front of a cloth backdrop, their playful moments giving way to a flurry of kisses. It is cited as the earliest on-screen kiss between a Black couple. Rediscovered in 2017 at a Louisiana estate sale by Dino Everett, a film archivist at the University of Southern California, the clip was thought to be lost for many years (four years later, an extended version was rediscovered in Norway). As film scholar Allyson Nadia Field notes, the late 19th century was marked by the proliferation of racist caricatures in popular culture, from cartoons and minstrel shows to early American cinema. "Something Good - Negro Kiss," then, stands out as a rare anomaly, depicting Black people as both ordinary and glamorous in a snapshot of love and joy.

Clips from both versions of "Something Good — Negro Kiss" open "Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898-1971," the second major exhibition at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. Though brief, their inclusion is a fitting prelude to the exhibition and its larger commitment to exploring how the influence of Black artists on early cinema led to the creation of a new canon of visual images.

On view until April 9, 2023, the exhibition charts the cinematic contributions of Black artists, behind and in front of the camera, from the silent era to the early '70s, stopping just before the dawn of the Blaxploitation period, a brash film movement marked by anti-establishment genre flicks made for Black audiences that centered on oppression-fighting and stylish Black characters. Covering 73 years, the show includes rare film excerpts, scripts, costumes, props and other archival materials. "We're looking at the breadth and scope of [Black film history]," explained co-curator Rhea L. Combs, director of curatorial affairs at the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery, during a Zoom call with KCET Artbound. "We wanted to expand people's understanding of American cinema. Since the beginning of this technology, since the beginning of this exciting boom, Black people have been there."

Over the last five years, Combs worked alongside co-curator Doris Berger, vice president of curatorial affairs at the Academy Museum, to develop the exhibition, which provided the opportunity to "dig deep into collections all across the country and even around the world," Combs notes. The curatorial team received additional support from an advisory panel made up of scholars, curators and filmmakers, including Ava DuVernay, Charles Burnett and Shola Lynch. The result is a first-of-its-kind retrospective, one that reorients and "widen[s] the U.S. film canon" as Berger points out, by recovering the lesser-known impacts of Black creatives on the cinematic medium, from race films to soundies (short musical films that predate music videos) to political documentaries. Spread across seven galleries, "Regeneration" is organized by broad themes like Stars and Icons, which highlights artists working within the Hollywood studio system and their offscreen lives, and Freedom Movements, which chronicles the ripple effects of the Civil Rights Movement on depictions of Black people in postwar Hollywood films.

In addition to highlighting legends like Hattie McDaniel, Dorothy Dandridge, Sidney Poitier and Melvin Van Peebles, the exhibition gives ample space to early pioneers like director Oscar Micheaux and actress Nina Mae McKinney, artists who carved out their own alternative careers through race films. Popular from the 1910-1940s, race films were movies produced for Black audiences starring an all-Black cast. These movies — melodramas, westerns, comedies, adventure yarns, and more — were produced by independent enterprises like Lincoln Motion Picture Company in Los Angeles, founded by brothers Noble and George Perry Johnson, and considered to be one of the earliest Black-owned film production houses. Unlike mainstream Hollywood movies of the time, which relegated Black actors to secondary roles as servants or other flat stereotypes pulled from minstrelsy, race films tapped into the real concerns of Black Americans, tackling topics like colorism, class issues, migration, gender inequality, spiritual crises and more. These films were shown exclusively at Black theaters, as well as nontraditional locations like churches and schools. One gallery dives into the legacy of race films, noting how many of these movies have been lost or only exist in fragments. Thankfully, surviving movie posters, which are displayed across two walls, give visitors an idea of this creatively fertile period.

Micheaux is another significant figure from this time — he is considered to be the country's first major Black American filmmaker. Born to parents who were formerly enslaved, Micheaux worked a variety of jobs, including a successful homesteader, before shifting his attention to film. He wrote several novels, one of which became the basis for his first self-financed silent feature, "The Homesteader" (1919). From then until 1948, Michaeux worked tirelessly, writing, directing, producing and distributing 44 films that provided complex roles for actors like Evelyn Preer and Paul Robeson. Made inexpensively and with a DIY spirit, his films courted controversy, exploring taboos like interracial relationships and racial injustices like job discrimination and lynching, as with 1920's "Within Our Gates." Combs explains, "We really showcase that there were independent filmmakers, like Micheaux and the Lincoln Motion Picture Company, that were creating these stories that had flourishes of what it meant to be a Black person living in America, and what that looked like at that time."

Race films became so popular that Hollywood began making their own studio films with all-Black casts, usually musicals that starred performers like Cab Calloway, Lena Horne and Ethel Waters. Other performers, like Josephine Baker and Nina Mae McKinney, fed up with the lack of opportunities in segregated Hollywood, pursued international careers. McKinney, an ebullient performer who was also an accomplished singer and dancer, made a splash in "Hallelujah" (1929), her screen debut and one of the first all-Black films produced by a major studio. Though she signed a contract with MGM, mainstream Hollywood had no interest in nurturing Black stars with good roles, and her career never reached the heights it should have.

Outside of the physical exhibition, the curators have organized satellite programming that will continue the conversations sparked by the show. There will be a catalog, a curriculum guide, a two-day summit in February and screenings, which provide a rare opportunity to see these films and experience its power live with an audience

Highlights from the film series, which kicks off later this year, include "Stormy Weather," (1943), which features a gravity-defying staircase routine from the Nicholas Brothers hailed by Ava DuVernay as "one of the best sequences ever recorded on film" and "Harlem on the Prairie" (1937), a race film starring singing cowboy Herb Jefferies, previously thought to be lost. Another premiere is "Black Chariot" (1971), a drama about a Los Angeles drifter who gets involved with a revolutionary group. Written and directed by Robert Goodwin, the film has not been shown in theaters in over 50 years. As I made my way through the last gallery, dedicated to indie filmmakers in the '60s and early '70s, I began to see the pulsing through-line connecting renegades like Micheaux to artists like Goodwin, Madeline Anderson and William Greaves.

"Regeneration" joins other recovery projects like the collection "Pioneers of African-American Cinema," curated by Charles Musser and Jacqueline N. Stewart (current director of the Academy Museum), as well as curator and screenwriter Maya Cade's Black Film Archive, an evolving registry of culturally significant Black films available to stream. Taken together, these efforts complicate the usual narratives we tell about American film, revealing the tenacity of Black creativity while also charting the myriad ways artists sought to represent their own experiences. When asked what they hope visitors will gain from the show, the curators point to the title. Despite the challenges of American racism, Black cinema has carved its own paths, finding ways to flourish within and without the studio system. Although the success of artists like DuVernay or Barry Jenkins may signal a new shift in Hollywood, as Berger reminds, their presence in the film industry is not new. Comb agrees, adding, "That's why it's important to expand the canon, to let people know that there are artists that predate Spike Lee, Van Peebles and Micheaux. Hopefully these people will be an inspiration for the future creators."

Scroll down to view more images of "Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898-1971" at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures.