Pacific Rim Artists Are Given the Limelight at OCMA's California-Pacific Triennial

When the Orange County Museum of Art (OCMA) launched the California-Pacific Triennial in 2013, it became the first California museum to survey the work of Pacific Rim artists. The Triennial — the offspring of the California Biennial, introduced at OCMA in 1984 — thereby became a distinctly more global event than its predecessor.

As Dan Cameron, curator of the 2013 Triennial explains: “SoCal museums had never looked at the Pacific Rim as a point of reference for the state's current and future demographic, with all the cultural, political, and economic implications.” He further acknowledged that our state’s multiethnic life and culture are often determined by migration from South America and Asia. His aim then was to place artists working in California within this broader global network. Cameron (today an independent New York City curator) organized the 2013 exhibition featuring contemporary paintings, illustrations, sculpture, video, light, sound installations and more from countries bordering the Pacific Ocean.

“In Orange County the cultural influence of the Pacific Rim is ever present.”

The 2017 Triennial “Building as Ever,” curated by OCMA senior curator Cassandra Coblentz, running through September 3rd, shares the basic aim of Cameron’s exhibition, because as she says, “In Orange County the cultural influence of the Pacific Rim is ever present.” Yet, there are dissimilarities. A chief difference is this year’s focus on architecture, and especially on the ephemeral nature of buildings. Or as Coblentz writes in the accompanying catalog, it affords “an opportunity to think deeply about what it means to simultaneously build up and tear down architectural structures” and to “respond to the question of permanence relative to the built environment.” Philosophically, most of the installations in the show are conceptual in nature. Salvadoran Ronald Morán’s “Intangible Dialogues 1-21” (2017), as one example, is a geometric sculptural piece made of thread, spanning its specifically designated gallery space. In fact, the time-based or work-in-progress aspects of many installations in the show add to their conceptual qualities.

“Building as Ever," featuring 25 individual projects by artists from 11 countries across Asia and North and South America, includes drawing, painting, sculpture, photography, video and multimedia pieces. An additional 26th project is the exhibition catalog; or as Coblentz writes: “This fluid sense of artist/architect/writer extends to this accompanying book.” Indeed, the catalog elucidates what architecture may not be in our contemporary world; the book also clearly describes the individual projects in the show, some of which are as "fluid" in nature as the show as a whole.

The first project in the exhibition, just outside the museum entrance, is by Los Angeles-based Renée Lotenero. This installation, “Stucco vs. Stone” (2017) is comprised of blown-up photos mounted onto plywood of classic decaying European buildings. This disorienting project includes medieval and Gothic style structures, most appearing to fall down on each other. Coblentz explains that architectural ruins, which provide a record of history, are valued enough to merit preservation. Lotenero’s project is also reminiscent of Banksy’s "Dismaland", a post-apocalyptic “bemusement park,” installed in the U.K. in 2015, and of the “Dismayland” Gothic monstrosity paintings by Costa Mesa-based artist Jeff Gillette, also cited in the Banksy article.

A similarly dystopian installation is in the entryway just before the main galleries. “This is Architecture” (2017) by Mexico City-based Santiago Borja is a six-foot long grave, created by removing a concrete slab from the museum floor. Exploring the significance of materiality, the artist states, “the ‘presence’ of something absent has a spiritual connotation that is itself rarely found in modernism.”

Just inside the entryway, “China House Great Journey” (2017) by Chilean artist Pilar Quinteros explores the history Santa Ana’s Chinatown,which was intentionally burned down in 1906 by white supremacists of that age. To accomplish her goal, the artist focuses on a Newport Beach landmark, China House, built in 1914 and demolished in 1987 to make way for new housing. Her wooden model of the pink Chinese style house installed on a pedestal, beckons visitors to view her documentary film in a nearby room. The 15-minute film depicts the artist walking, while dragging the rope-bound China House, from the old Santa Ana City Hall through Irvine, Newport Beach and finally to the beach, near the spot where China House once stood—an eight-hour journey. Sitting on the sand at dusk she rebuilds the house, which is now in many pieces, then stands up and kicks the structure until it falls apart, perhaps symbolizing the transient nature of cherished homes and communities. The film proceeds to examine the history of Santa Ana’s Chinatown through old newspaper clippings and historical records, as well as the history of China House including images of its demolition.

A significantly larger structure in the exhibition is by Vancouver-based Cedric Bomford. “The Embassy or Under a Flag of Convenience” (2017) is a site-specific scaffolding constructed of steel, wood and reclaimed materials. This five-story edifice, similar to structures erected for buildings undergoing construction, is the first of several pop-ups, which the artist intends to put up in different places. The scaffolding’s temporary nature addresses Orange County’s and SoCal’s ongoing disregard for longevity as builders continue to construct faceless tract housing. The structure also invites visitors to climb up its rickety stairs to its top, where they can view nearby Fashion Island and slivers of the Pacific Ocean.

Also featuring scaffolding are 12 digital chromogenic prints, focusing on massive construction sites in downtown Los Angeles as it undergoes rapid development. L.A.-based Alex Slade’s M.O. is to explore with these images, “issues of gentrification, power, and control over economies of place/space,” while echoing similar growth trends throughout the Pacific Rim. With titles as “Wilshire and Figueroa, Wilshire Grand Center, Hanjin Group, Seoul, South Korea (73 story tower. Total budget $1.1 billion)” (2015), these photos exhibit deft understanding of composition and color, while displaying hints of familiar L.A. sights including Disney Hall. These construction sites’s immense girth, seeming to overtake downtown, may cause viewers to long for the old downtown Bunker Hill neighborhood, with its elegant Victorian homes, which was demolished in the 1950s and 60s.

Another classic now-decimated Los Angeles site was Hollywood Park Racetrack, in business for 75 years. Just before it closed in 2013, L.A.- based Michele Asselin photographed its large, neglected spaces, resulting in 25,000 images. From these, she chose 14 pictures, depicting jockeys, workers and race track devotees for her “Clubhouse Turn” series. These moody archival prints of nearly empty spaces include the mezzanine and a horseman’s lounge. They “focus on the psychology of space, memory, and witnessing,” the catalog explains, and “create a poignant and telling disconnect that speaks to the ultimate demise of a once thriving place.”

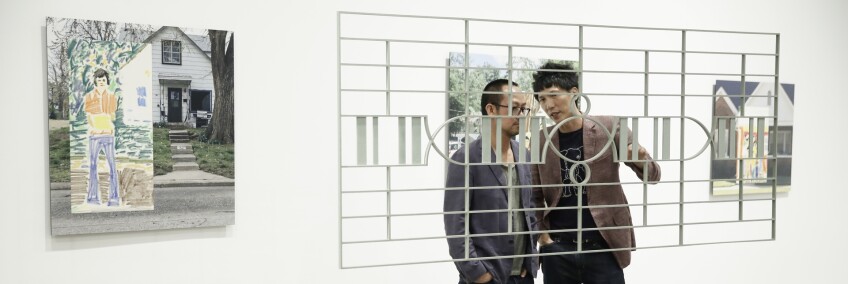

The most painterly project in the show consists of seven mixed media works by Saigon-born Trong Gia Nguyen who now resides in Ho Chi Minh City and Brooklyn. These oil pastels on canvas and mounted inkjet prints (2017) relate the story of Nguyen, who was four years old when his family fled Vietnam in 1975. He then grew up with his siblings in the United States. After returning to his country of origin, he unearthed old family photos of his several U.S. homes and superimposed semi-abstract paintings of his family onto them. His poignant collaged mixed media works evoke memory, the passage of time, and the experiences of an Asian family as it strived to assimilate in a foreign culture. Of all the installations in this show, these works are the most involving as personal histories.

“Building as Ever” does not depict pretty images. In fact some of the installations such as Santiago Borja’s grave are difficult to engage with. Yet the exhibition has a profound message for this age of constant flux with its changing power structures, political disorientation and the displacement of people from across the globe. It is also is a visual treatise on the transitory nature of architecture today. Or as Stewart Brand writes in the catalog, “Architecture has trapped itself by insisting it is the ‘art of building.’ It might be reborn if it redefined its job as the ‘design science of the life of buildings.’”

Top Image: California-Pacific Triennial 2017 opening night | Ryan Miller