Like Queer Church on Sundays: Ozz Supper Club Gave Young LGBTQ a Place to Belong

The neon sign that teased us from the freeway. The roomy parking lot adjacent to the convenient motel next door. Clandestine pre-parties in crowded cars, the line stretching along a dark wall lit up in rainbow colors. The butch bouncer with the power to grant or deny coveted drink wristbands. The Scooby Snacks and the Flaming Dr. Peppers. The piano lounge, video games and pool tables. The hottest music, the chillest vibe. The crowds, the friends new and old, the rush of it all. And of course, Raja.

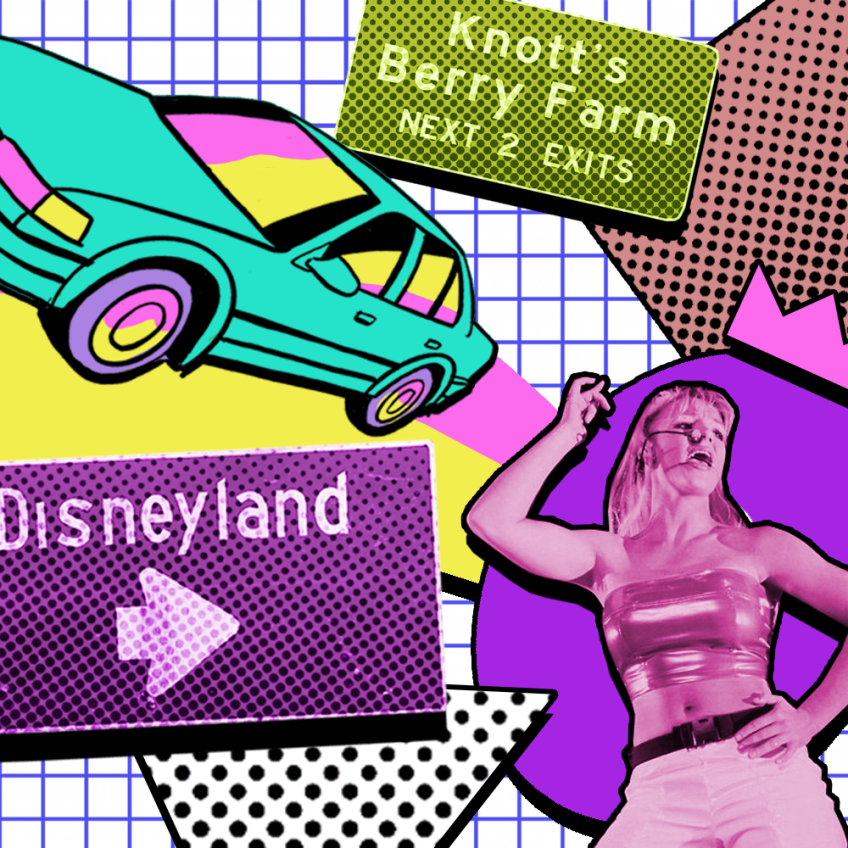

If you remember Ozz Supper Club — popularly known as Ozz — in Buena Park, California, you remember all of this and then some: maybe your first queer kiss or sultry same-sex dance, or a bad breakup on the smoking patio or the cute girl who bought you a beer and got your number, but never called. Maybe your outfits: hat-to-the back, polo and cargo shorts sagging with a chunky Nokia cell phone and disposable camera, if you brought one. Or the shiny halter top and new heels that made you sparkle on the dance floor.

Rene Boudewijn "Bodie" Kohler owned Ozz from 1990 until 2005. The queer supper and dance club operated in Buena Park off the Beach Boulevard exit from the Santa Ana Freeway, a centralized location near Knotts Berry Farm that proved to be key to Ozz's success for years as one of the few LGBTQ+ bars in Orange County and greater Los Angeles outside of the more famous 'gay' scene of West Hollywood. When the city sold the strip of freeway-adjacent land for development, the building that housed Ozz and others around it were condemned. Bodie signed the demolition papers, and in October 2005, CalTrans bulldozed Ozz. Three years later, Bodie would serve time in federal prison for failing to report door fees to the club while it was in operation.

Many of us who went to Ozz during its heyday were oblivious to any problems that maybe have precipitated the club's unceremonious ending. Instead, we remembered a magical time of budding queerness and mutual bonding at the gay club near Knotts. Ozz marks a time before social media and smart phones, when we had to make queer community the 'old fashioned way.'

And if you ever went to Ozz, chances are you went on a Sunday nights, when under-21s were welcomed and Raja ruled the world.

Finding the Land of Ozz

"I remember it like it was yesterday."

It was 1999, and Laura Luna P just experienced a defining moment in her queerness at Ozz.

"I had my first hot, steamy, same-sex dance. It was to Mariah Carey's Heartbreaker mix. She was a Latina with curly hair, clear lip gloss, wore a white button-down shirt and jeans," recalls Luna P, who attended Ozz with mixed group of friends from 1999-2000.

Over two decades later, the self-described bon-vivant, voluptuary and mestiza/Latinx dyke of 43 remembers the crisp white of her dance partner's shirt, the crunchy gel-curl of hair and her Dolce & Gabbana wafting around them in the pulsing club air. It's an Ozz memory that affirmed who she was at a time when she felt awkward and unseen, says Luna P, and it will be with her forever.

Luna P was 19, working at LAX, and living in a "crash pad" with other airline workers when she found Ozz. She first went with her roommates, including three gay men and another bisexual woman. Some were over 21 and others, like Luna P, were not. Ozz was 21+ every night except Sundays, when it welcomed 18-and-overs. So Sundays became their night.

Despite the long drive from the LAX area to Buena Park after a hard day's work at the airport, Luna P and her friends looked forward to hitting up Ozz. She described the "whole scene" just getting there — Destiny's Child or Britney Spears bumping through the car's speakers, the excitement upon seeing the freeway signs for Knott's Berry Farm ("that meant we were almost there"), pulling into the parking lot and watching the line grow as dance music thumps away inside.

"The whole Ozz vibe was so cool because it was mostly POC [people of color], and the DJs played mostly R&B, hip hop and pop," remembers Luna P. "There was this old school dinner area with a piano and a bar. Even the line and parking lot were cruising areas. Our crowd was so mixed, and there was something for all of us."

Ozz presented a clear alternative to West Hollywood for Luna P and her friends, who favored the suburban "supper club" thirty miles away in Orange County over the world-famous "WeHo" gay scene much closer to their Westchester home.

"As a bisexual woman of color, especially at the time, I didn't vibe with WeHo," she says.

Ozz felt like community in a way other places didn't.Angela Lesaca

Ozz had that 'not-West Hollywood' appeal to many of us who resided to the south and east of downtown Los Angeles, particularly lesbians and other queer women of color who found the white-gazing, boy-centric world of WeHo off-putting or inaccessible.

Angela Lesaca loved Ozz for that reason.

The 49-year-old Filipinx chemist and dedicated Prince fan attended Ozz from 2000 to 2002. She was 28 and had just come out when she first went to Ozz with a new friend she met on a 1-800 party line. Lesaca would end up meeting her first girlfriend that night.

"Ozz felt like community in a way other places didn't," she said. "If you were already nervous about being out, Ozz was that place where you could just be yourself, be queer and have a great time with people from all walks of life. It was 'come as you are' and not as clique-y as WeHo."

Lesaca lived six miles from Ozz, an easy drive down the 5 from her Norwalk home. "Ozz was in a central location near Knott's. The freeway made it easy to get to, parking was a breeze, the music and DJs were great," she said. "They catered to everyone. All my local friends would be there."

Full disclosure: I was one of these local friends who lived 15 minutes away from Ozz. I met Lesaca on her first night there; it was mine, too. I was 26 and back home in Whittier after dropping out of a doctoral program at Indiana University. Ozz was instrumental in helping me find and build a new queer community at a time I felt lost in my own hometown after leaving grad school, gay friends and a girlfriend behind in the Midwest. Meeting Lesaca at Ozz that night over twenty years ago was lifechanging in this regard. We're good friends to this day.

Lesaca also liked the way the club's space promoted diversity and intergenerational mingling among its patrons, rare in queer urban nightlife culture that tends to skew youth-ward. At Ozz, we saw older gay men dining in the piano lounge, beer-sipping dykes playing pool, wide-eyed 'baby gays' looking for someone with a 21+ wristband to sneak them drinks.

"But we talked to each other, and it wasn't weird. Older or younger, we were all there to hang out and have a good time. I wish it was still there."

We reminisced about Bonnie the Bartender, who looked like Pat Benatar and poured us stiff novelty drinks like Scooby Snacks and Apple Jacks. We remembered wild, Flaming Dr. Pepper-fueled nights that took us careening from corner to corner around Ozz, chasing phone numbers and first kisses from the pool tables and video games to the smoking patio and dancefloor. You knew the night was over when the DJ played a slow song and the lights came on. And of course, there was "Gay Denny's" after the club, when the unassuming family diner near Knotts Berry Farm turned into a loud Ozz annex full of sweaty drag queens and buzzed clubgoers scarfing get-sober food at 2 a.m.

"Ozz became one big party," said Lesaca.

Especially on Sunday nights.

Sunday Night Church

"The only Ozz I knew was on Sunday night."

From the end of his freshman year in 1997 at UC San Diego through graduation in 2000, educator Francisco Sánchez (an alias) lived for Sundays in Buena Park.

Two carloads carrying Sánchez and his group of "gay boys" led by their lesbian "matriarch," all UCSD students, drove 90 miles up the 5 to "church" and back every Sunday night. By the time they closed down Ozz, downed cheeseburgers and Cokes at "Gay Denny's," and made it back to their dorms after the long ride home, it was 4 or 5 a.m. Monday morning. Class was at 9.

"It was that kind of affair," remembered Sánchez. "But we didn't care. We needed that mental health break, that dose of Ozz before resuming life at school every week as queer students of color on that campus, in La Jolla."

Sánchez grew up in queer-friendly Long Beach, a city that elected its first gay Latino mayor in 2014. However, when he came out at age 15 in the early-1990s, his mother did not approve. He describes his queer youth as "sheltered" and did not attend his first gay club until college. Sánchez found Hillcrest, San Diego's answer to West Hollywood, uncomfortable and unwelcoming.

"Even though it was closer to campus, going to Hillcrest was an alien experience," said Sánchez, citing the rich-white-gay vibe that made WeHo similarly uninviting to Laura Luna P, Angela Lesaca and many others.

It was more than just the physical space. All that energy had to go somewhere, so it spilled onto the parking lot, the line, and Gay Denny's.Francisco Sánchez

Student life in tony La Jolla was not much better for Sánchez and his friends in the late 1990s, who all hailed from perpetually underrepresented groups or communities at the competitive UC campus . "La Jolla was rich, white and unfriendly to students. Our group was Latino, Filipino and Black," explained Sánchez. "A friend who had already been to Ozz told us we should go. For the first time, I saw myself in people around me. Ozz was my re-entrance into the gay world, like a second coming-out."

At 42, he recollects the red bubble vest he wore and the electric anticipation he felt upon seeing Ozz's neon sign flashing from the freeway. "Geography had a lot to do with what made Ozz special," he says. "You didn't have to drive all the way into West L. A. or Hollywood from San Diego. We'd see Disneyland, Knotts, and we knew we were almost there. Ozz was like that — fun, special, like a theme park for us."

Like Luna P and Lesaca, Sánchez remembers Ozz's expansive scene that burst beyond its walls. "Ozz had a reach," he noted. He loved seeing the "sea of Brown faces" pouring out of the club after a euphoric night of dancing to the likes of TLC, Janet Jackson and Shakira. "It was more than just the physical space. All that energy had to go somewhere, so it spilled onto the parking lot, the line, and Gay Denny's."

And then there was Raja, our legendary drag queen hostess and performer on Sunday nights at Ozz.

"Raja's show was the premise for our trip from San Diego," recalls Sánchez. He, Luna P, Lesaca and I all shared similar memories of arriving early at Ozz on Sundays before the cover charge kicked in, knowing to wait politely for the afternoon country-western line-dancing to end. Then the dance floor belonged to us and later, to Raja.

"It was the first time I saw a drag show," said Sánchez. "Ozz during Raja's show was such a wonderful space, an intimate space, it felt like someone's house or living room."

And live we did in Raja's room.

Raja's World

Before RuPaul and the world watched her compete on "Drag Race" Season 3 as Raja Gemini, Ozz's Sunday night faithful knew her simply as Raja, the drag queen hostess and performer whose legendary shows packed the club every week.

When the lights went down and the music changed around midnight, it was Raja Time. "You knew to sit right down wherever you were in the club, even in the middle of the dance floor, boom!" recalled Sánchez. "And here comes Raja strutting out of the corner to Missy Elliot, [wearing] a Supa Dupa Fly outfit, doing this number. I couldn't get enough of that."

Raja defined Sunday nights at Ozz, and Sunday nights, arguably, defined Ozz.

The Los Angeles Times took notice of the club's "biggest crowds" and the "line wrapping around the building [as] proof" of Raja's allure. "Host Raja, who stands 6 feet 3 before donning six-inch stilettos, is not only stunning, but also is one funny drag queen," reported the Times in 1999.

"Ozz changed my life," Raja Gemini told "Artbound." "Whenever people mention it, I think of very fond and colorful, almost dreamlike memories. If you remember, you remember."

Model, performer, makeup artist, "Drag Race" champion, and "Simpsons"guest star Raja Gemini was born Sutan Amrull in Baldwin Park, California. She moved to Indonesia as a child, then returned to the San Gabriel Valley. A graduate of La Puente's Bassett High School, Raja attended California State University, Fullerton, where she studied art.

"It was the 1990s. I was eighteen and already experimenting with drag, going to Arena [in Hollywood], dabbling in the scene," said Raja. Once on campus, she joined an LGBT group whose members introduced her to Ozz.

Raja recalls going there "dressed up" for the first time, the idea of performing already on her mind. "I was this young queen introducing myself to the other queens." Soon after, Raja got her shot at hosting.

"The dance floor was my space," she recalled. "I got to experiment with performing, and it was a way to figure out who I am. Ozz opened my eyes to drag that came before me and other queer styles of performance like cabaret and burlesque. It exposed me to things I wouldn't have found and taught me a whole lot. Ozz molded me into who I am today."

The supermodel era also inspired Raja's drag shows at Ozz. Raja represented a new generation of queens coming of age in the 1990s who were more interested in sashaying down runways like Cindy Crawford, Linda Evangelista and Naomi Campbell than being Cher, Madonna or Whitney for the night.

"The supermodels were the highest form of femininity for me," said Raja. "A lot of drag involved impersonation, and I wasn't really an impersonator. I wanted to do drag like I saw in L.A. It was more about presence, fashion. I wanted to do something different." RuPaul's 1993 hit, "Supermodel (You Better Work)," reflects this emerging distinction Raja saw between impersonation and creating a unique haute-couture drag persona.

At Ozz, Raja had the freedom she needed to hone her craft. She performed what she called "alternative drag," where her sets included "vignettes and dioramas" to songs by Janet Jackson, Björk and Portishead. Her costumes and makeup ranged from a Lisa Lisa-inspired 'freestyle' look to sleek sophistication.

"I created numbers that evoked the emotion of the song, which allowed me to set myself apart," said Raja. "And I had tattoos! In the nineties, drag queens didn't have tattoos." These numbers would become concepts that informed and propelled her post-Ozz career and drag stardom.

Raja knew her audiences well and played to their tastes, desires and sensibilities. "There was a room full of hood-rats at Ozz on Sundays, and I invited them because that's who I am. The 5 freeway connects a lot of places and that location mattered. That was my community. I don't think the owners anticipated it."

And community loved Raja, showing up for her weekly, like religion.

Sunday nights, especially Raja's shows, were powerful and necessary for our group to connect and bond as queer people of color.Francisco Sánchez

"Raja was iconic before 'Drag Race,'" said Luna P, who had her first hot lesbian dance at Ozz. "She was a vision. Her make up at the time was new and modern, like a supermodel. As a fem, I paid attention to her visual transformations."

For Sánchez, the former San Diego student, "Sunday nights, especially Raja's shows, were powerful and necessary for our group to connect and bond as queer people of color and as students trying to get our education a UC. It was our mass, and we couldn't miss it."

"There was an innocence to it," Raja reminisces. "People sat on the dance floor and watched me perform like in a family room. No one had smartphones! There was no social media! Everyone was present and ready, and people were in the moment. I miss that very much, that presence. That is missing now, and I'm not sure if that can be truly recreated."

Queen Raja held court at Ozz for nearly eight years. "The work I did was that I brought in POC," she stated proudly. "Ozz was an everybody club, a one-stop shop." She even hosted an inaugural burlesque night starring one Dita Von Teese, "before she was famous."

At the end of our conversation, Raja reflected on the significance of Ozz's meaning to her and all the regulars who remember it.

"I only hope today's queer culture youth can find spaces like that, to flourish, for experimentation," she said. "I feel quite fortunate to have had that in Ozz. How many places are even like that anymore? Or were like that?"

An Author's Bittersweet Note

Writing about gay, lesbian, and queer bars of the past, that no longer exist, poses particular challenges, and Ozz is no exception. Their histories are not collected in libraries or city archives; the only paper documents I found were the demolition record and articles about the owner's federal tax sentence. Photos from Ozz days were hard to come by.

A recent VinePair article outlined some of the obstacles of documenting these bars of a bygone era. "This is especially true for queer of color communities that formed on what were once the fringes of a metropolitan area but have since been absorbed and gentrified," reports VinePair. One researcher calls bars like Ozz "phantoms of the past." Only memories can resurrect these once-thriving vital queer spaces.

Because all we have are the memories.

On a recent afternoon, I drove my old route down Beach Boulevard to Ozz, except Ozz was gone. A giant CarMax sells Nissans and Toyotas on a lot where our glittering gay club once stood. Exotic-sounding Manchester Boulevard, where Ozz lived and changed countless lives for fifteen years, no longer exists: it was widened, paved over, and renamed Auto Center Drive when used car superstore moved in. Nothing at all reminiscent of the queer playground so fondly remembered off this freeway exit.

And it's just plain old Denny's now, still there by Knott's, though nothing particularly gay about it on Sundays any more.

Ozz is gone: the building, the parking lot, the line, the butch bouncer at the door who checked IDs for wristbands. But the neon Ozz sign will always shine bright, the Scooby Snacks will always flow, and Raja will always look Supa Dupa fly in the minds of those who remember like it was yesterday.