Of Oil Fields, Neon Signs and Tree Shade: The Fires That Fuel Los Angeles

Illustrations by Vera Valentine

“Elemental L.A.” is an exploration of an Angeleno “sense of place” using the four classical elements — air, earth, water, and fire — as guides.

It erupted into the catwalk and hurried along until it reached the patent collection stored in the northwest stacks. … The temperature reached 900 degrees, and the stacks' steel shelves brightened from gray to white, as if illuminated from within. Soon, glistening and nearly molten, they glowed cherry red. Then they twisted and slumped, pitching their books into the fire.Susan Orleans, "The Library Book"

Progress

Skeins of black ink unwind from eight factory smokestacks in a bird's-eye view of Los Angeles printed in 1877. In a 1909 view, there are more than fifty. Progress is the color of smoke in these views, but progress needed fire.

When we think of this place, we think of abundance. In 1877, Los Angeles didn't have enough. The engines of foundries, the kilns of brickyards and the mash tuns of breweries needed fuel, and Los Angeles had almost nothing to burn. Itinerant Mexican woodcutters went deep into foothill arroyos to find firewood. Tons of eucalyptus charcoal had to be freighted from Australia. The price of mined coal was five times what it was in the East.

Gayle M. Groenendaal, in her analysis of the "fuel crisis" of the 1870s, found that all "easily accessible timber had been removed so that lumber had to be imported from Northern California or Oregon…and timber for fuel was becoming scarce." "No tree was spared," remembered Los Angeles diarist Harris Newmark, "and I have known magnificent oaks to be wantonly felled."

The explanation for the number of smokestacks in 1909 is oil. In 1892, Edward Doheny and Charles Canfield brought in the first well in the City Oil Field, driving down the cost of fuel and setting off an industrial boom that promised never to end. Finally, there was enough fire. Industrial smoke rose over the city and hung in the still air.

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, at anchor in the Bay of Smokes in 1542, had seen the future of Los Angeles.

Industrial freedom

The glum slab of the former Los Angeles Times building on First Street is a memorial. It remembers the 21 pressmen and linotype operators who were flung into fire and collapsing masonry when the original Times building was bombed by union organizers on an early October morning in 1910.

The burning printer's ink flooding the pressroom that October morning did more. It wrecked the labor movement in Los Angeles. Socialist Job Harriman, the leading candidate for mayor, lost the 1911 election because the union men he defended were convicted of the bombing. The local labor council lost most of its union members because it also had supported the bombers. The American Federation of Labor abandoned organizing in Los Angeles. Los Angeles employers redoubled their efforts to suppress unions and maintain an "open shop" regime backed by the Times. Union membership in Los Angeles did not begin to show signs of regrowth until the late 1950s.

The former Times building, completed in 1939, is more than a memorial. It remains a blunt assertion that the Times and its industrial allies had successfully bent the politics of Los Angeles toward conservative reaction. The anti-union rallying cry "True Industrial Freedom" is still carved deeply into the building's red granite façade.

Liquid fire

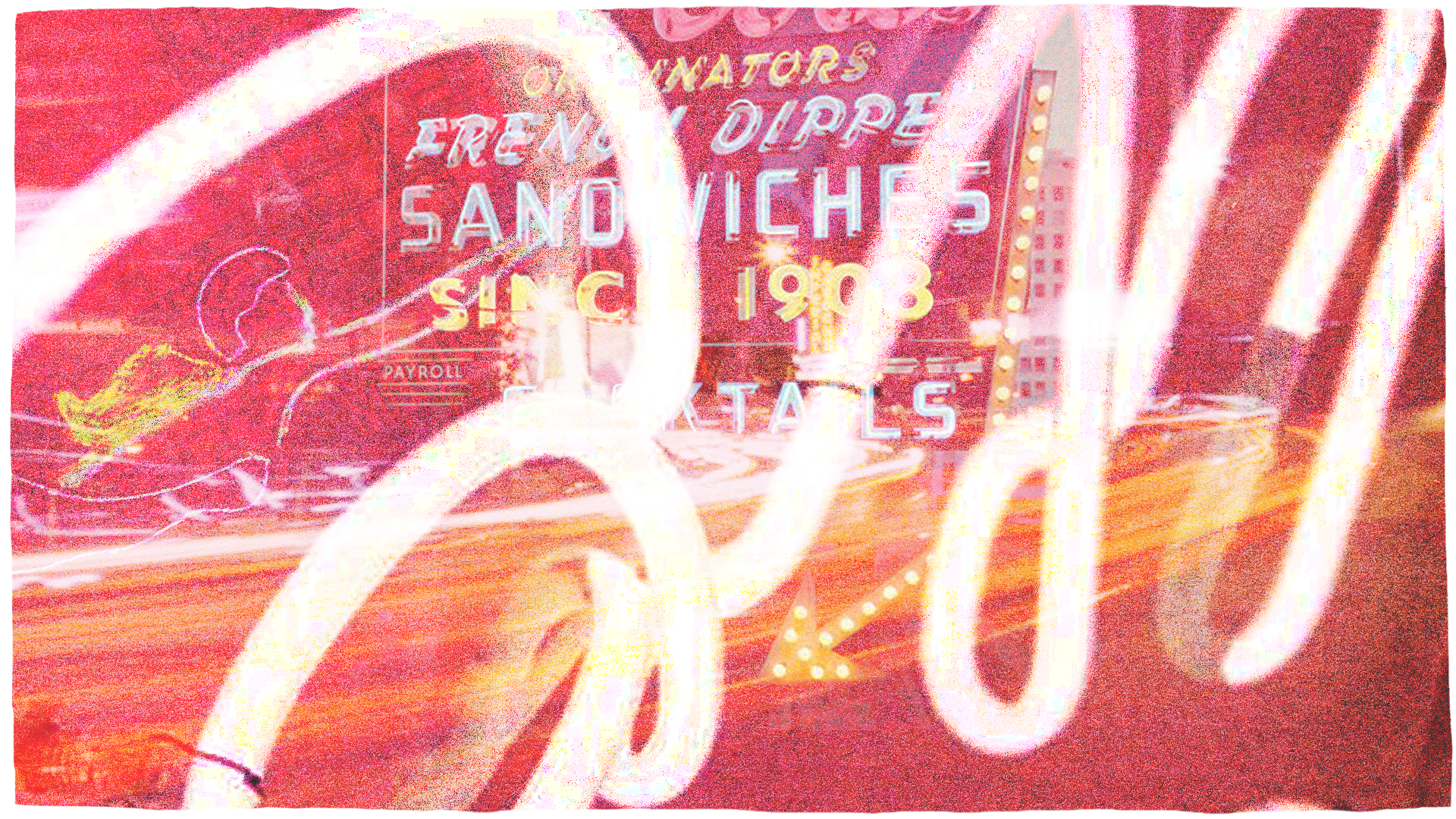

There's a myth that the first neon sign in America — in cursive script spelling Packard, a make of cars — was installed in 1923 on Wilshire Boulevard. The Museum of Neon Art in Glendale doubts the myth is true. Even so, neon's webs of light, excited by electricity and more brilliant than Technicolor, suited Los Angeles. By the 1930s, neon "spectaculars" blazed, blinked and animated above all-night markets, boxy movie houses and prosaic apartment blocks. In daylight, the drabness of commercial Los Angeles stands out; with neon and night, the city is transfigured.

In February 1942, Mayor Fletcher Bowron ordered the signs to go dark as a wartime precaution, extinguishing something gaudy and marvelous. Not all the signs were relighted when the war ended. They remained, surprisingly durable, until longing for what historian Kevin Starr called "the magic of the night" caused the city's Cultural Affairs Department in the 1990s to relight surviving neon signs along Wilshire and Hollywood boulevards. "If Paris is the City of Light," Starr said in 1999, "L.A. is the City of Neon."

It's another part of the myth that the city's first neon signs — intensely orange-red — looked to startled Angelenos like "liquid fire." But they really did.

Already on fire

In September 1939, the federal Home Owners Loan Corporation published a map of Los Angeles County. The map rated neighborhoods for their risk to mortgage lenders. Green for neighborhoods with the lowest risk — white and upper middle class. Blue for lesser-ranked white neighborhoods. Most of the map is colored yellow, showing a high level of risk in ethnically diverse, working-class neighborhoods. The map warned lenders away from the parts of Los Angeles that are mostly Black, Latinx, Asian or Jewish. These neighborhoods are colored bright red as if already on fire.

"The city burning is Los Angeles's deepest image of itself…and at the time of the 1965 Watts riots what struck the imagination most indelibly were the fires," Joan Didion wrote in "Slouching Towards Bethlehem."

"For hours I've been transfixed, watching childhood landmarks swallowed up in the surprisingly liquid aspects of billowing smoke and flames — stores, streets, memories, futures. I'm watching my old neighborhood blister, turn to embers, rendered entirely foreign," Lynell George wrote in "No Crystal Stair" remembering the aftermath in 1992 of the verdict in the Rodney G. King beating.

Self-immolation becomes us. In burned-over neighborhoods south of downtown, thirty years after 1992, some empty lots still gape in the streetscape. In Long Beach, the city put low, white fences around them. Those vacant places remember the fire last time better than we do.

Politics of shade

Beyond the towers of downtown — eastward across the river and southward into the flats — a canopy of trees covers about 10% of sidewalks and storefronts. In neighborhoods above Sunset, shade softens the noontime sun on 53%. Urbanists Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris and Renia Ehrenfeucht report that household income is the single variable that controls the density of a neighborhood's tree canopy. Rachel Malarich, the city's first forest officer, points to the Home Owners Loan Corporation map. Redlining in 1939 also predicts almost perfectly where narrow sidewalks, lack of trees and civic disinvestment outlaw shade today.

Law enforcement is another enemy of shade. As soon as LAPD surveillance cameras go up in a neighborhood, city crews radically cut back the limbs of mature trees, extinguishing shade and often killing the tree.

Tomorrow's Los Angeles will be hotter. Days of extreme heat (defined as more than 95 degrees) will certainly double and may increase by four times. Shade will be the immaterial infrastructure to make a walkable, bikeable, transit-oriented Los Angeles possible.

Los Angeles is planting trees, anticipating the effects of climate change. But they may be the wrong trees for the neighborhoods of the working poor. Trees that spread a broad canopy of shade also buckle narrow sidewalks, interfere with overhead wires and obscure sightlines at driveway aprons. Concrete and drivers have priority over pedestrians and transit users waiting for the next bus under the pitiless noontime sun.

Heliocentric

There is a 176-foot tower on Mount Wilson in the mountains above Pasadena. On every clear day since 1912, mirrors at the top of the tower have sent the sun's image 150 feet down to an observation table. Sunspots are tracked. Currents on the sun's surface are charted. From one perspective, the solar tower looks like an impossibly tall oil derrick. From another, it looks like a Martian tripod from the "War of the Worlds."

Pasadena — indeed, much of Los Angeles — is a product of the sunshine the observatory collects. Waves of East Coast and Midwest vacationers came here for the warmth of the winter sun; many stayed. John Fante, in his novel "Ask The Dust," doubted they found what they came for. "The old folk from Indiana and Iowa and Illinois…came here by train and by automobile to the land of sunshine, to die in the sun, with just enough money to live until the sun killed them. … And when they got here they found that other and greater thieves had already taken possession, that even the sun belonged to the others."

The other telescopes on Mount Wilson — once the largest in the world — no longer observe distant suns. Light pollution from Los Angeles washes out the night sky. The basin glows after dark, a cauldron of electric fire.

Further Exploration

The arboreal history of Los Angeles is told in "Trees in Paradise: A California History" (Norton, 2013) by Jared Farmer.

A gallery of classic Los Angeles neon signage is online at Public Art in Los Angeles.

UCLA's Alan D. Leve Center for Jewish Studies hosts the online exhibition "Jewish Histories in Multiethnic Boyle Heights" in which the effects of redlining East Los Angeles are detailed.

"No Crystal Stair: African-Americans in the City of Angels" (Verso, 1992) by Lynell George is an immediate, vivid, and personal account of the Black experience in 1990s Los Angeles.