Now More Than Ever: The Need for Alternative Cultural Spaces

It’s no secret that major U.S. museums have a lot of work to do in creating a more diverse and equitable landscape for artists and curators. While large institutions have become more self-aware over the years — especially recently with the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement — the move toward multicultural representation is still inching forward at a glacial pace. Alternative cultural spaces in Los Angeles like Watts Towers Arts Center and Self Help Graphics & Art (SHG) have historically been filling in the holes left behind in a white-centric art world by giving underrepresented artists a platform and serving their communities in thoughtful ways.

Many of these ethnic cultural spaces have been around for decades as a hub for history, arts and social activism. As these institutions are growing older, they’re adapting to changing audiences and tastes, and finding ways to connect the past with the present. In today’s socio-political climate where people are dealing with racial prejudices, fighting for immigration rights, and navigating a pandemic, the spirit of these spaces makes them just as vital as when they first opened. These centers have been pivotal in addressing the direct needs of their communities, from economic to cultural struggles, that are often overlooked by more mainstream spaces.

The Rise of Alternative Cultural Spaces

L.A. Times culture writer, Carolina Miranda, has found that alternative cultural spaces have always existed as a concept. “Wherever you have what is considered mainstream, you have artists saying, ‘Wait a minute, there are other ideas to consider,’ like Salon des Refusés in Paris,” she said. “Certainly, the Civil Rights movement combined with the [Black] Power movement of the ‘70s really shaped it ….

“It’s during this period in which people are thinking socially, politically and economically about issues of equity and how they connect with race and ethnicity. This is a time when those artists aren’t getting a lot of airtime in mainstream arts institutions. Then it becomes vital to provide these other spaces where other opinions and ideas can be explored.”

The desire to change how minorities were represented in the media and arts was the driving force behind the formation of culturally specific museums like the California African American Museum (CAAM), according to its Executive Director, George Davis. Davis recalled that when he visited museums or watched movies growing up, he didn’t see himself represented in them.

“If I watched a Western movie, I didn't see African Americans in it, although [25%] of cowboys were African Americans,” Davis said. “And when I watched the news, I would see African Americans maybe getting arrested for something, but I wouldn’t see the anchorman [or] the mayors [as African Americans].”

Davis said that Black representation in the art world has changed since then, and a lot of larger museums that previously didn’t exhibit major Black artists are doing it now. CAAM, which is located in Exposition Park in South L.A. and was founded in 1977, takes the approach of supporting emerging Black artists in its programming.

“I used to joke about [how] the holy water gets sprinkled on you once you are validated by museums like us,” Davis said. “Then the bigger museums and the more mainstream [ones] feel more comfortable doing exhibits [with you].”

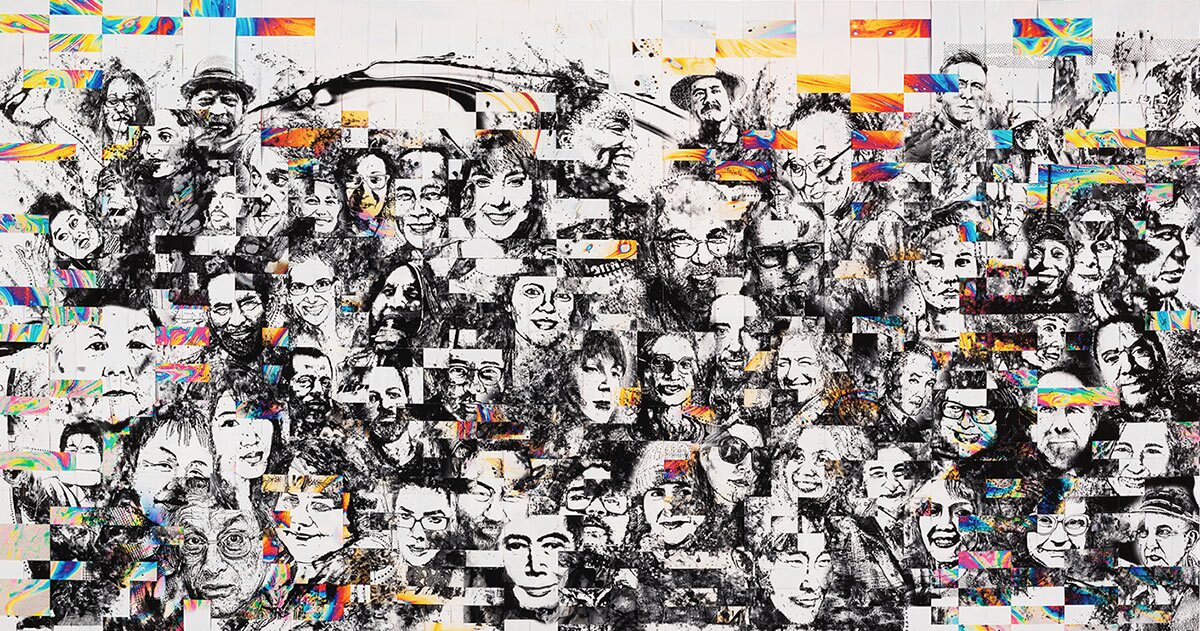

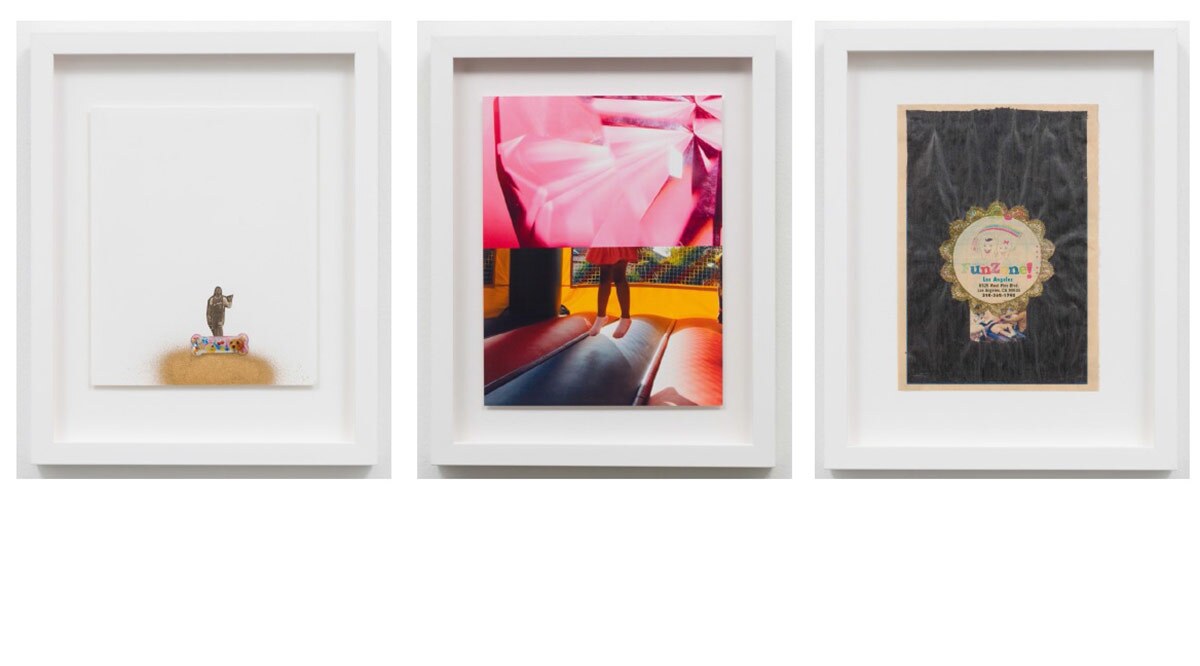

Click through below to see images from CAAM's most recent exhibition, "Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: Neither Fish, Flesh, nor Fowl," which was open for only two weeks before COVID-19 forced it to close.

Similarly, SHG, a printmaking studio and community center in Boyle Heights that hosts workshops, exhibitions and cultural events like its annual Día de los Muertos, also got its start in the 1970s. The organization has fostered up-and-coming Chicano and Latino talent since its beginning. It was spearhead by Sister Karen Boccalero, a Franciscan nun and artist, along with artists Carlos Bueno, Antonio Ibañez and Frank Hernandez.

“If you look back at the history and the context of the Eastside at that time, there was a lot of social unrest,” said SHG’s Executive Director, Betty Avila. She pointed to the Chicano Moratorium, a series of peaceful anti-war rallies that turned violent in 1970 when Rubén Salazar, a Los Angeles Times journalist who wrote extensively about the plight of the Chicano community in L.A, was killed when he was struck by a deputy sheriff’s tear gas projectile. There were the East L.A. Walkouts in 1968, when Chicano high school students, teachers and faculty members held a series of protests against the L.A. Unified School District to improve the quality of education at their schools. And prior to that, freeways were built through an already redlined East L.A., which caused long-lasting and devastating effects on the communities.

“Sister Karen was always very clear about wanting to open up opportunities for artists of color, for Chicanos and Chicano artists who weren't going to easily have access to more mainstream arts institutions,” Avila said. “[She wanted] to give a space for creative healing, but also open up doors into the art world for those artists who wanted to go down that path.”

The behind-the-scenes work that SHG does for its community is needed just as much today as back then. In SHG’s longstanding printmaking program, artists are able to use the center’s studio and create prints. The proceeds of their sales are split between the artist and the organization, with SHG subsidizing the program.

The pandemic has been an especially trying time not only for institutions, which have had to close their doors to the public and pivot programming, but for artists as well. “We're very aware of the amount of people on the Eastside who have been impacted by COVID directly,” Avila said. “It's been intense for our community.”

In response, Avila has opened up SHG’s studio space on a minimal basis to working artists who need a place to create art so that they can sell their work and have a form of income. As SHG has had to take much of its Día de los Muertos programming to virtual and outdoor spaces, its team has also been trying to find ways to help artists make money. They’ve commissioned artists to offer face painting and shoebox altar-making workshops online, as well as make altars for public viewings at Grand Park in downtown L.A. and malls in Culver City and Century City.

When Black Lives Matter uprisings took place around the country in response to the murder of George Floyd in May, it was hard for Avila to not be able to open up SHG so that artists could make posters for the cause, something that would normally have happened if not for the pandemic. Instead, her team asked a couple of artists to create poster designs that they then printed and handed out for free to community members during a drive-by event. It was so popular that they added more days, and even received calls from the Smithsonian and the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. asking for the posters for their collections documenting this time in history.

The Programs That Enrich L.A.’s Cultural Fabric

One of the major differences between large and small art institutions is that the former moves very slowly. “It’s like turning an oil tanker: You need five miles to make a right turn,” Miranda said. “Big decisions have to be approved by boards, and acquisitions go through committees, and maybe those committees only meet a handful of times a year, so they tend to be slow. Any museum exhibition [there] is the product of an idea that was hatched three to five to 10 years ago.”

That’s where SHG differs, in that it is much more agile and open to new ideas. “It's very much in partnership with community members, whether they’re individual artists or nonprofit community partners who are using this space as well,” Avila said. “What really makes Self Help Graphics unique is that flexibility and nimbleness within its artistic mission that serves the complex and the nuanced needs of the community.”

Click through below to see photos from Self Help Graphics' Día de los Muertos workshops.

Sometimes SHG is the driver of a program or event, and other times it’s the passenger when the space is being used by another artist, collective or community member. In doing so, they have learned to let go of the reins a bit and be comfortable with the discomfort of letting others run the show.

“We've worked with young people from teenagers to folks in their early 20s, who are really just starting to get their feet wet in cultural programming as cultural workers,” Avila said. “And so there's some level of mentorship that has to happen there. But for other spaces that run a little bit differently, that's kind of a scary proposition. Like, ‘How are we going to hand over the reins to somebody that's so young, that’s so green?’ That's where Self Help Graphics is really different in that we welcome it and we support and give structure where needed.”

The Chinese American Museum [CAMLA], which is located at the El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument by Union Station, has been documenting the Chinese American experience since its founding in 2003 and offers something mainstream museums don’t.

“We're able to tell more [Chinese American] stories [than at a major museum] where they only dedicate an exhibit [to it on a surface level] maybe once every four years or so,” said CAMLA’s Executive Director, Michael Truong. “It's really that aspect of our institution, [of telling stories] through the lens of the Chinese American community that makes us unique.”

In October, CAMLA virtually commemorated the racially-motivated Los Angeles Chinese Massacre of 1871 with honorees voicing their concerns over the recent rise of anti-Asian racism and hate crimes. They also hosted a virtual panel discussion in June that discussed the 1982 murder of Vincent Chin, a hate crime that spurred Asian Americans to band together.

“The resources that we provide at the museum are [look at] how history plays a role, especially now, but not just in the pandemic, with anti-Asian [sentiment] and the struggle for equality throughout the nation and world,” Truong said. “Our role in these times is to reflect upon history and think about what ways we can learn from the mistakes of the past, and not have it repeat.”

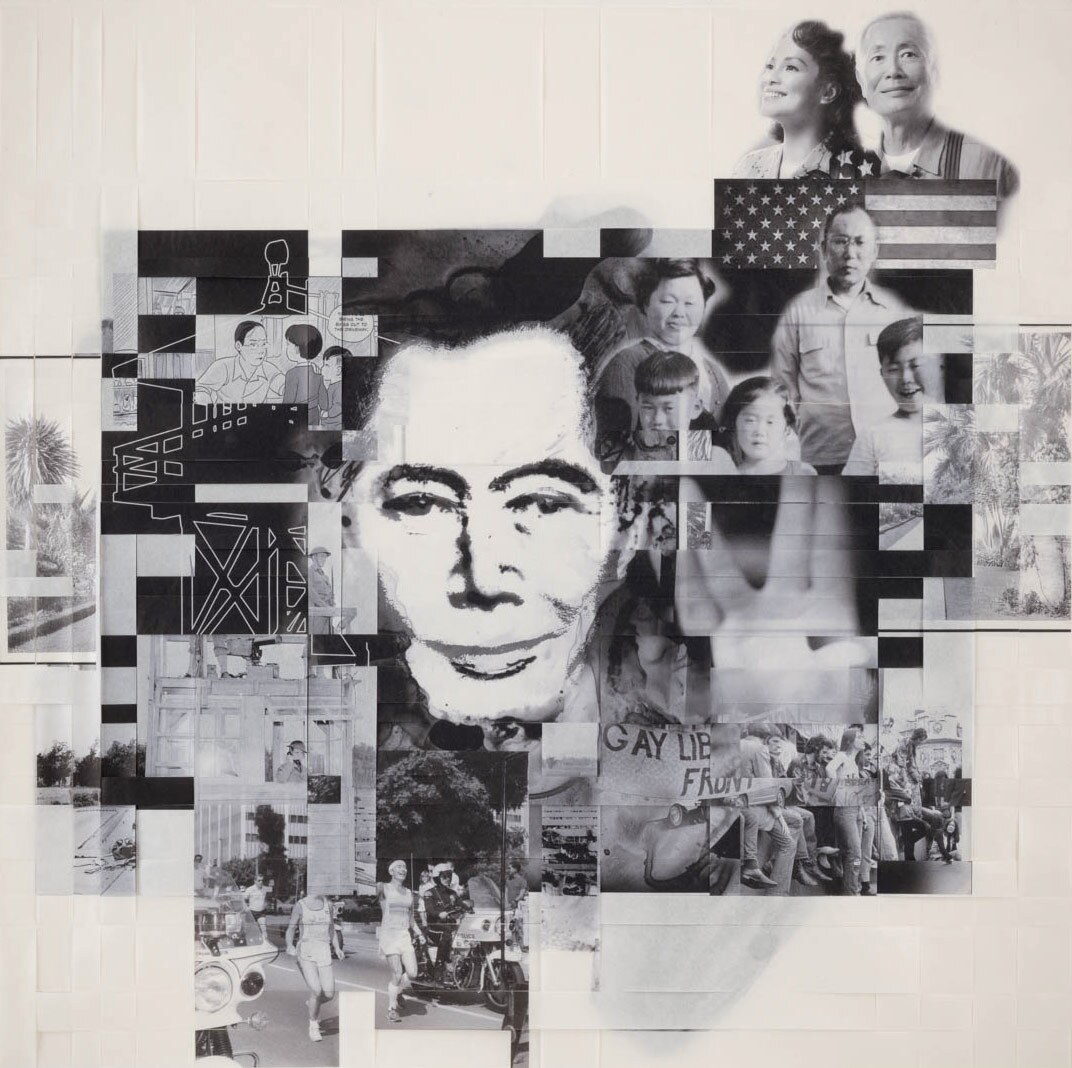

In addition to helping Chinese Americans explore their own identity and educating others outside of it about its culture through history and pop culture, CAM aims to illustrate the diversity within the Chinese American experience. Every year, CAMLA partners with Lambda Literary, an organization that advocates for LGBTQ+ writers, for an event that showcases the intersectionality of Asian American identity and the LGBTQ+ community.

The Blind Spots in Larger Institutions

When a Williams College-funded study on the diversity of artists in major U.S. museums was published in 2019, the diversity problem was finally quantified. In analyzing the collections of 18 major U.S. institutions, researchers found that 85% of the artists are white. In contrast, the U.S. Census Bureau estimated in 2019 that white people (who are non-Hispanic and non-Latino) only make up 60% of the country’s population.

L.A. is no exception. “In a city that’s 50% Latino, you’d think those [large] museums would have a better track record of showing work by, say, contemporary Chicano artists, but they don’t,” Miranda said. “To be clear, it’s not that Chicano artists don’t make it into the museum at all — they have — but it’s usually in group shows. The solo exhibitions go to other artists, and it’s the solo exhibitions that are the career builders.”

Miranda reported in the L.A. Times last year that the last time a Chicano artist had a solo show at a major L.A. museum was at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in 2017. In her research, she couldn’t find proof of a Chicano artist having a solo show at the Hammer Museum or the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles (MOCA) in the last decade.

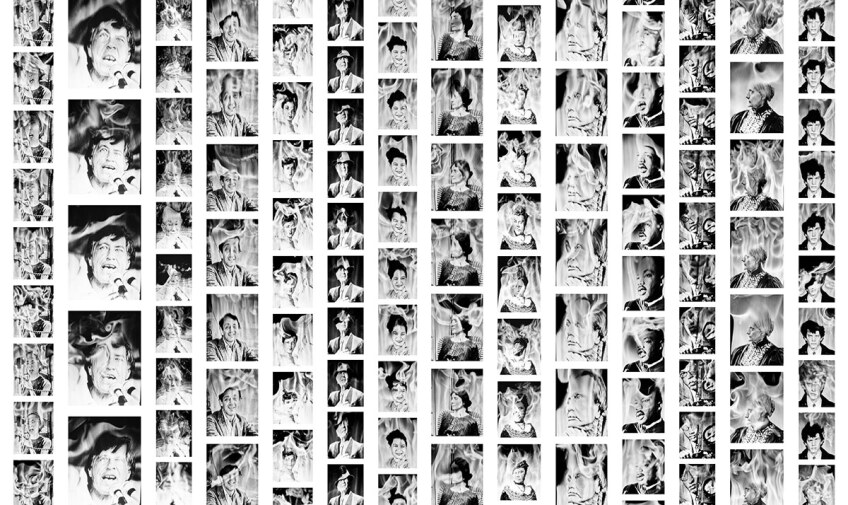

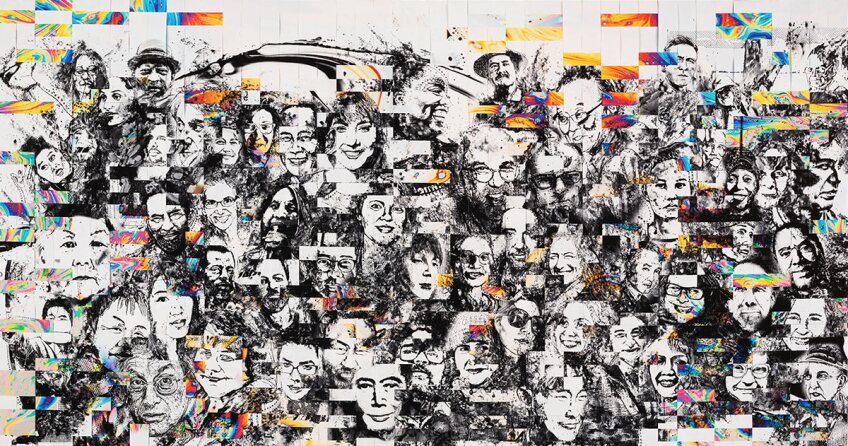

Click through below to see photos from JANM's latest exhibition, "Transcendients," which "honors individuals who advocate and fight for those who face discrimination, prejudice, and inequality at borders both real and imagined."

Where these larger institutions fail to represent the communities they serve, that’s where spaces like The Vincent Price Art Museum (VPAM) at East L.A. College fill the gaps. “VPAM has been key to providing exhibitions to artists —either their first shows or maybe their first solo shows — of Asian and Latino backgrounds,” Miranda said. “They are really embedded in the community, which sits right on that line between Monterey Park and East L.A. I think they have been just critical to serving that community. You are going to see artists there that just aren’t getting shown as much in other parts of town.”

While VPAM is temporarily closed to the public right now, they've recently been using virtual spaces like Instagram Live to introduce artists like Dulce Soledad Ibarra and Crenshaw Dairy Mart founder noé olivas through short interviews.

Miranda was especially impressed by VPAM’s "Regeneración: Three Generations of Revolutionary Ideology" exhibition that ran from 2018 to 2019. It explored the ways revolutionary and activist ideas were shared between people in the U.S. and Mexico, with Los Angeles as a central point. “That is an important exhibition whether it’s told at VPAM or anywhere else,” Miranda said. “L.A.’s connection to Mexico and the fact that L.A. was once part of Mexico should be articulated regularly. If it weren’t for organizations like VPAM, you wouldn’t be hearing these stories as much. I think even as the art world has started to become more self-aware about this kind of stuff they still have a ways to go.”

It’s not just diversity in artist representation that’s a glaring issue, but also with curators at museums. “We all know that equitable shows start with equitable curating,” Miranda said.

The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation released a report on U.S. art museum staff demographics and found that in 2018, only 20% of those holding intellectual leadership positions in museums were people of color. However, there was some positive change: This figure had increased by 5% from 2015.

It’s through the efforts from the likes of The Getty Marrow Undergraduate Internship program, which has been running over 25 years, that change is moving in a positive direction. The organization has funded over 3,300 internships for students of underrepresented cultural backgrounds at local arts institutions and continues that work experience with professional development assistance for its alumni. It’s an act of patience to water these seeds and watch them grow. Miranda said we’re now seeing the effects of the program; Avila is an alumni and is now running SHG.

Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE), a space in Hollywood that features a wide range of artists from different cultural backgrounds, is also working toward creating a more equitable curator landscape. The venue, which was founded in 1978 by a group that included Chicano artists like Harry Gamboa, Gronk and Robert Gil de Montes, has an Emerging Curator’s Program that selects a rising curator to organize their own show. LACE provides a budget and collaborates with the curator. “I think that program has been important to shaping the landscape of the city,” Miranda said.

How Cultural Spaces are Staying Relevant

When Davis was brought in to lead CAAM in 2015, it was a mission of his that cultural spaces like it didn’t get stuck in a time warp. He realized that what was relevant to the community back when CAAM first opened isn’t to today’s younger generation.

“So we brought in really bright, well-educated, very well-thought-of, and frankly, younger curators both in history and art,” Davis said. “We just really changed exhibits quickly and we got much more aggressive with social media. We found artists that were up and coming, that were getting a lot of buzz.”

Cameron Shaw, CAAM’s deputy director and chief curator, is continually reevaluating what is the institution's role as a Black museum in this changing landscape. “I think one of the things that's become really critical for us is to think about the role that we provide, specifically for artists in terms of the possibility of them engaging with urgent issues, and to do that in a healing and liberatory framework,” Shaw said. “And to really offer both financial and administrative support to allow Black artists to move beyond just simply showing their work, and to have the opportunity to build projects that allow them to bring revolutionary ideas into the world.”

Shaw added that because CAAM is unique in that it is both an art and history museum, it can use what is in its gallery in conversation with some of the most pressing issues of our time — including climate change, changing economies and labor relations, and surveillance — as they intersect with Black life.

She’s also found a way to build unique partnerships that broaden CAAM’s reach. Most recently, CAAM worked with KCRW-FM to co-commission artwork from Lynnée Denise, that came in the form of a sonic project and panel discussion that aired on the radio.

“This is a time where museums can be very creative about the channels that they're using and their modes of dissemination in how they are staying connected with audiences," Shaw said. “It's opened up some opportunities for our institution that we'll continue to take advantage of, as we move into the future.”

Davis said as a result of their efforts, they’ve quadrupled the attendance at CAAM during his tenure.

Click through below to see some of CAAM's recent acquisitions to the permanent collection.

He’s been cognizant of CAAM’s changing audience demographics. About 30 to 35% of the museum’s audience is not African American, many of it is Latino. In an effort to speak to this growing audience, Davis has secured more strategic alliances, such as this year’s joint exhibition with LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes on Afro Latinos, with a solo exhibition of works by Sula Bermudez-Silverman.

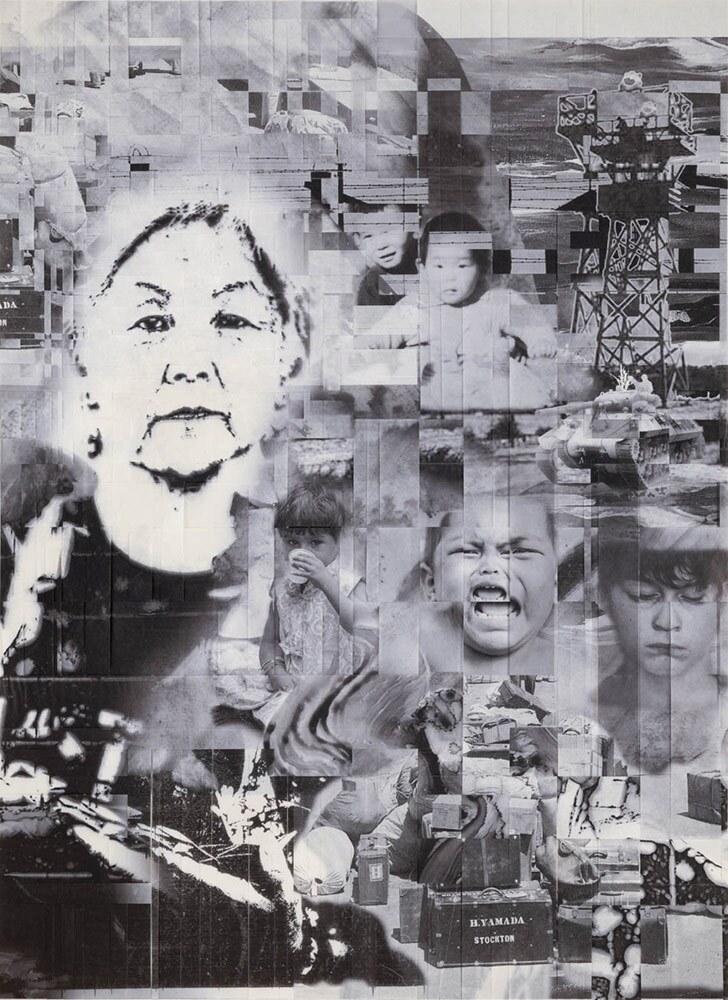

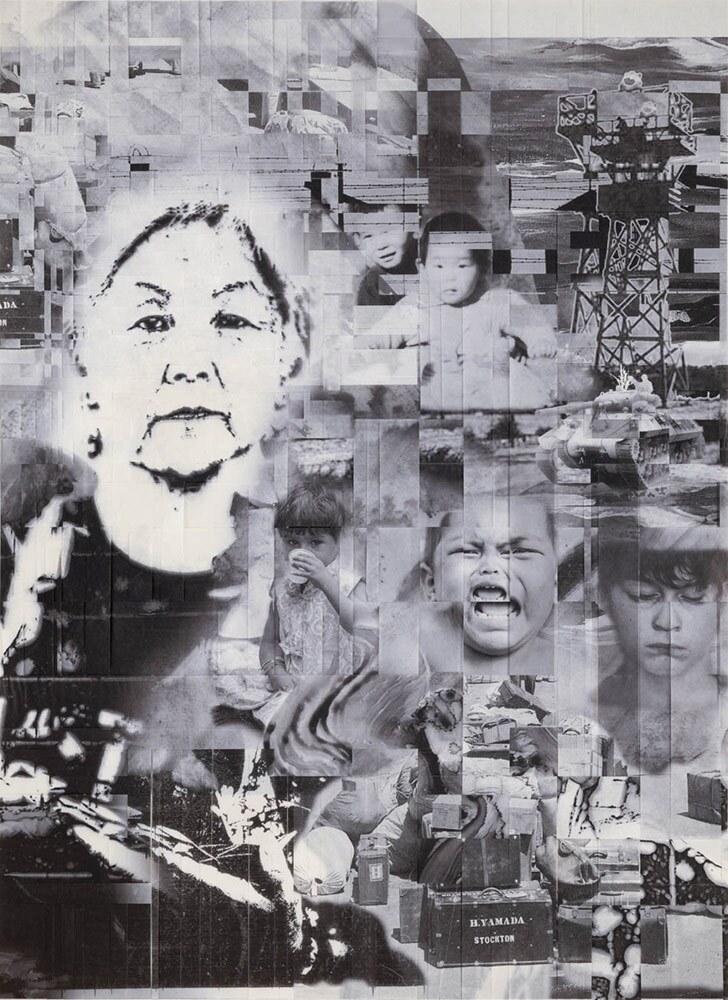

The Japanese American National Museum (JANM), which was established in 1985, has found itself staying relevant with its own civil rights history as it mirrors the current climate surrounding race and immigration issues.

As JANM moved its programming online this year, the museum’s YouTube channel has been home to a wealth of educational and historical videos and recorded panel discussions. The museum has also deepened collaborations and partnerships. One of its upcoming panels presented in conjunction with the USC Pacific Asia Museum and CAM on Nov. 19 discusses the history of Black-Asian solidarity and how we can use that knowledge for the future.

“We've always done programming that looks at issues of diversity, dismissiveness and discrimination, and the role of, of ethnicity and culture, particularly within the Asian American experience,” said JANM Executive Director Ann Burroughs. “We started looking at it in a much more holistic way.”

When JANM curated an exhibition in 2017 to commemorate the 75th anniversary of Executive Order 9066, the directive that forced Japanese internment, it resonated with students who visited the museum (20,000 schoolchildren visit the museum every year, many of whom come from low-income communities and Title 1 schools; the museum raises money for the schools’ bus trips to JANM). It was a pivotal year in which President Donald Trump signed executive orders for a Muslim ban and for the U.S. government to begin building a wall along the Mexico-U.S. border.

“For the students who were coming, they could actually see their own stories, their own fears depicted in the museum,” Burroughs said. “Many of the teachers reached out to us and asked us to help them think through with how they could deal with these issues that were coming up in the classroom. So even with something specific to Japanese American history, we were actually able to leverage that to help teachers talk about issues of tolerance and compassion.”

Just before the pandemic, Avila discussed having to think more broadly about supporting the economic needs of SHG’s artists in a different way. Her team has been discussing ways to build programming that bridge the community with creative industry jobs.

“I don’t take it lightly that our community is so connected, that [SHG is] a place where people get married or they have baby showers; or in 2019, we actually had an end-of-life ceremony for a community elder in the building,” Avila said. “And I take it is as my responsibility to understand how we can do that better and how I can set up the infrastructure within the organization so, that being said, we are in a place [where we’re financially] thriving as an organization and not in the sort of survival mode that culturally-specific organizations often find themselves in.”

Top Image: Installation view of "Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: Neither Fish, Flesh, nor Fowl" at CAAM featuring colorful dollhouses made of sugar. | Elon Schoenholz