Locke High: The Inner City Music Program that Wowed the Nation

On a hot August night in Watts, mere days after the explosion of the 1965 rebellion and the imposition of a citywide curfew, a man named William Hammond left his family's dry-cleaning business on Avalon Boulevard to visit a nearby friend. Wandering through a dark open lot at the corner of 111th and San Pedro Streets where a block of homes had been razed, he lit a cigarette. In the brief flame of his lighter, Hammond saw armed silhouettes rise out of the shadows. He had wandered unawares into a National Guard bivouac. "They drew on me!" a shaken Hammond told his friend. "They could have killed me right there!"

The common wisdom is that Alain Leroy Locke Senior High School, which opened its doors 50 years ago this month, opened as a reform-minded response to the Watts rebellion. In truth, Locke was a response to the increasing overcrowding of South L.A.'s high schools. The open lot Bill Hammond walked though had not been razed by rioting but by municipal planning — in 1963, 5 million dollars had been approved by district voters and preliminary construction of the 25-acre campus designed to house 2,500 incoming students had already begun by June 1965. If anything, the Watts Rebellion actually created a new urgency for a new educational experiment. Locke, by sheer happenstance, ably fit the bill — the first new high school built in the central city in a half a century.

The nascent sports and academics programs needed time to develop and blossom, but what would first put the school's identity on the map hit the ground running because it had its origins two blocks south at Samuel Gompers Junior High. By the time he got the call offering him the job as Locke's new Music Department chair, Eagle Rock native (and USC grad) Donald Dustin had already created from the ground-up a blue-chip program at Gompers with a combination of organizational rigor and widescreen command of music history. Dustin became famous for his "Friday Challenges" — sort of like a jazz head-cutting contest where any student could challenge another for first-chair status. "Don allowed us to blossom," recalls Reggie Andrews, who was concertmaster at Gompers until he graduated in 1961. "He always put music a step up. We were playing college stuff in junior high school like 'Suite for Military Band' by Vaughn Williams and other things like that. He put repertoire out there and made us climb for it." But, as Andrews is quick to point out, Don Dustin was not the first music teacher at Locke. That honor went to a postal employee with no teaching credentials.

"My principal at Gompers wouldn't let me go over [to Locke] until the following Spring," recalls Dustin. "As a consequence, Frank Harris...was approached as a substitute to hold that position." Harris, a woodwind specialist from Shreveport, Louisiana, remembers being shown around the brand-new campus by Dr. Jim Taylor, the charismatic and avuncular Locke principal: "I was not thinking he was interviewing me at the time [until] we walked to the Music building. He opened the door and turned on the lights: 'Mr. Harris, this is your office.'" Harris, somewhat sheepishly, had to inform Taylor that he had no accreditation, but Harris' degree in instrumental music from Southern University in Baton Rouge plus his status as a just-discharged G.I. — not to mention the fact that the school board was short of teachers for new a school "in the ghetto" — helped smooth the process. "On the first day...I had exactly seven students for music: two violinists, a cello player, a trumpet player, a clarinet player, and one drummer. I said, 'Okay what we're gonna do is start talking and playing music...we're just gonna play with what we have.'"

Which at the time was not much — "all told, we probably had about 15-20 instruments," says Harris. But after about a week another student appeared at the door. And another. "By the end of the semester I probably had about 18 or 19 students, so I said, 'Well, we got a little group here — how about we do something for the football game? Let's just go out onto the stands and play.'" The crowd was delighted by the ragtag combo with donated instruments and moth-eaten and ill-fitting uniforms held together with safety pins and rope. "We didn't put up flyers or anything; it was just word of mouth. Another student would come in and then another and another...It was step-by-step...'Mr. Harris, can I come and play with the band?' We had fun with it, and that showed the other students who wanted to play that, 'Yes, absolutely you can do this.'" Harris rehearsed his charges daily and with a velvet-gloved iron hand, telling them, “Nobody can outplay us in anything. I don't care who it is. Don't you ever think there's anybody who can do this better than we can.”

Dustin and Harris built their talent pools utilizing a variety of ingenious recruiting methods. "Locke wasn't even a magnet school when it opened," says Dustin. "We weren't allowed to recruit from other schools. But when we would go off to a performance we'd schedule the buses an hour early and stop on the way at a junior high or elementary school and play. We'd do that often, and it built up a lot of interest." Soon students at other schools began pulling fire alarms just so they could come out and watch the Locke band on the field. "Frank and Don was a very unique thing and it can never be replicated — I know I've tried," notes Reggie Andrews. "That created one of the best 'feeder' programs around." Patrice Rushen, classically trained since age three and now an award-winning musician and composer, came to Locke from Henry Clay Junior High. "The teachers [at Locke] insisted that the kids get a well-rounded background," the keyboardist recalled in a 1999 interview. "I used to experiment with doing arrangements of popular tunes for the marching band...They gave me books to read [on] the ranges of the instruments, and so on. I would come in with these arrangements, and they would actually let me stand there and conduct them!...That was the first inkling I had that there was something I could do with music." Rushen would go on to work with such artists as Stevie Wonder, Prince and Michael Jackson.

More Stories about Locke High

Although LAUSD supplied teachers with the requisite giant orange binder of curriculum requirements (nicknamed "the Pumpkin"), Locke teachers still had a lot of leeway to adapt and improvise. Dustin would comb through bins of sheet music, buying up any scores by African-American composers that were "thematically relevant." When the Rockefeller Foundation, one of Locke's financial angels, donated a Volkswagen Transporter to the school, Dustin used it to get the kids off campus. "There was a social aspect to it that was very important," affirms Dustin's wife Kitty, who at the time taught Social Studies at Locke with the last name of Henninger. "Kids had a chance to spread their wings a bit and see other styles and ways of life." It led to some memorable experiences in culture shock. "One year, we were invited by the Transamerica Corporation to do a performance for industry and business CEOs in a big hotel in Laguna Beach," chuckles Dustin. "We threw all the kids in the van and drove down one night...We were well-received and served a beautiful dinner afterwards. I told one of the kids, 'If you don't know what to do, watch other people.' It came time for dessert, and I guess one of the waiters had figured out that we weren't from around there, so when one of the kids ordered chocolate mousse, he said, 'Would you like the tail or the head?'"

But Locke was still missing something. Dustin felt that Locke should have as good a jazz education program as Dorsey High's under Donald Simpson or Washington High's under Chuck Edwards. To this end, Dustin had been grooming one of his first and most promising students from Gompers, Reggie Andrews. The Watts native who grew up on 109th Street was a scholar with swagger, an autodidact who had finished Washington High in two and a half years and college at Pepperdine in under four. "As I went to school...I noticed that they didn't have any black music teachers in the public schools," says Andrews. "I thought about it: 'Do I want to try to be Herbie Hancock, or do I want to try to create Herbie Hancock?'" He opted for the latter, and, starting in 1968 as an afterschool program under the auspices of the Joint Enrichment Team (J.E.T.), a collaborative project between the Rockefeller Foundation and Cal State-LA, Andrews created the Msingi Jazz Workshop.

Msingi means "roots/foundation' in Swahili, and the combo stood out by playing lunchtimes at mostly white schools like University High wearing African dashikis. But, at a time when jazz was spiritually connected with civil rights and Afrocentric cultural movements, students who showed up wanting to play immediately like John Coltrane or Archie Shepp would be disappointed in Andrews' self-described "vocational" approach. "We don't teach our kids to appreciate creativity," he once said in a radio interview. "There's a whole progression to become creative; you just don't end up being creative. At one point, you have to just be able to hold on and participate — blow that note or play that scale. Andrews didn't even like using the word "jazz" and his students benefited. "We were also playing jazz as America’s classical music," noted Patrice Rushen. "That sort of opened up the vocabulary for other forms of contemporary music."

Two years into Locke's existence, the indications that what Dustin, Harris and Andrews were doing was working began to become apparent. "[Msingi] went to the Orange Coast Jazz Festival in Costa Mesa," says Andrews. "There were like five judges [including drummer] Shelly Manne and [bandleader] Gerald Wilson...After we played, they said, 'That's the first music we heard all day.'" And even before many of its players like Rushen graduated, the Music program was starting to pay dividends. Drummers Leon "Ndugu" Chancler and Raymond Pounds and trumpeter Danny Cortez were already landing professional gigs. "In Patrice's senior year, in September '71, we did the Monterey Jazz Festival...We didn't win the competition [but] that's how Orrin Keepnews saw her." The legendary jazz producer soon hooked Rushen up with Prestige Records, which released her solo debut “Prelusions” in 1974.

But even more important than vocation was the lesson of how talent can supersede lingering prejudices. In February 1970, Dustin and Harris took Locke's orchestra students to the 20th Annual Pacifica Music Clinic in Stockton. "It was always an interesting experience because at the time the judges didn't expect anything from the black kids," says Dustin. "Frank and I went into that room with our star players [clarinetist Cornelius Walker and violinist Sheila Ann Hinnant] to make sure that they were treated honestly." Out of 300 young competitors culled from 25 countries, Hinnant was chosen as concertmistress."[The prejudice] didn't happen so much after that," Dustin says. "We set the standard."

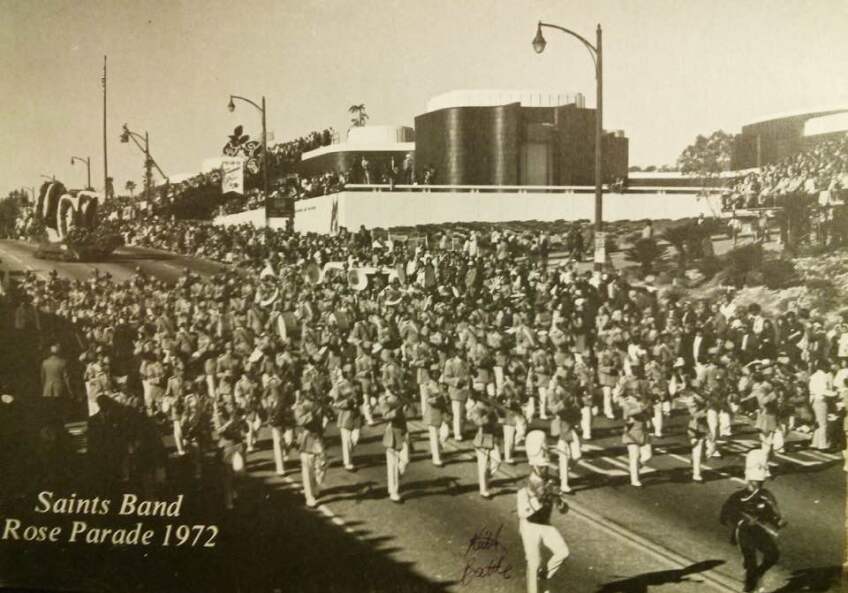

By 1969, Frank Harris and his Locke High Saints marching band — now 105-strong — were also on their way to setting a standard. "Many people admitted that they attended games chiefly to see the marching band at halftime," noted the L.A. Sentinel, "and several schools chose not to march at halftime rather than follow the 'Saints'"That November they emerged as the band to beat for competition for marching in the Tournament of Roses Parade. The reason was Harris' innovation: To extend the rote military precision with looser routines culled from the Louisiana tradition of "high-stepping" street bands. "It definitely had a New Orleans flavor to it," he affirms. "I didn't want just a military march...so when we opened up we'd march in twos on the whole field, and then we'd go into the real fine fast steps...We marched up to 152 steps-per-minute then we'd stop — POP! — then we'd go into our dance routines." Darryl Moore, a drummer for the Gardena High Mohicans vividly recalls the spectacle of the Saints. "When Locke High hits the field, it's like nothing but dust flying up in the air — boom! bam! bash! — and they'd march so fast [and] the drums were shaking the stands. They came to destroy us!" On November 20, 1969, Locke High School won the city championship. They became the first all-black marching band in the Tournament of Roses parade since just after World War II.

Sources

L.A. Sentinel, July 15, 1965. "Plan Street Improvement for Locke High School," p. B10.

L.A. Sentinel, February 26, 1970. "Locke Girl Wins Honors with Violin at Clinic," p. A3.

L.A. Sentinel, November 27, 1969. "Locke High's Band Goes Rose Bowling," p. B3.

Wendell Green, L.A. Sentinel, December 25, 1969. "Locke High Enters Bid to Rose Parade," pp. A7, B3.

Horace Tapscott: Musical Griot, 2016. Directed by Barbara McCullough.

Author interviews with Aman Kufahamu, Reggie Andrews, Frank Harris, Kitty Dustin

Top Image: Marching band drums | Ronen via iStockphoto