Last Punks in Print: Razorcake Has Been the Platform for Punks of Color For Over Two Decades

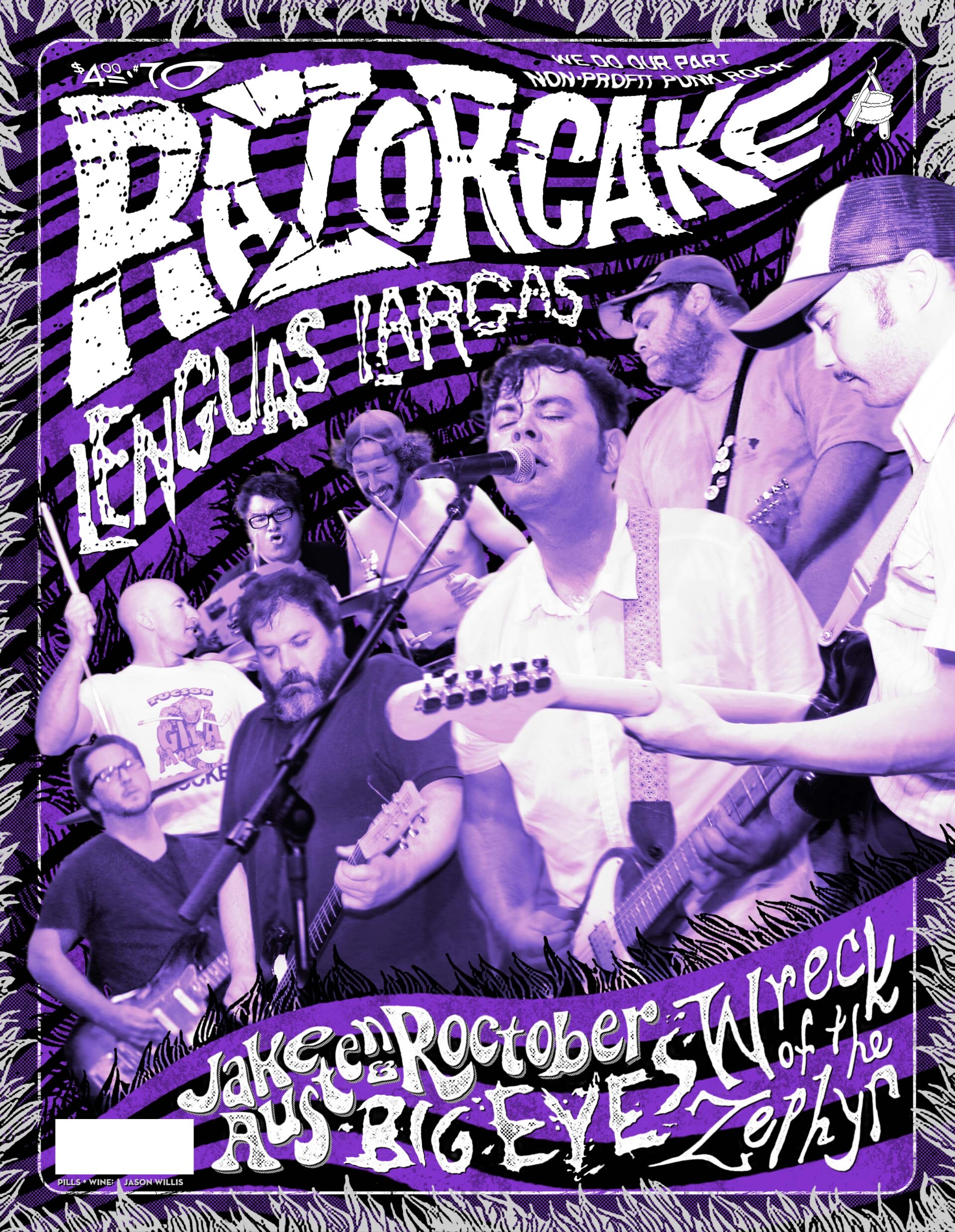

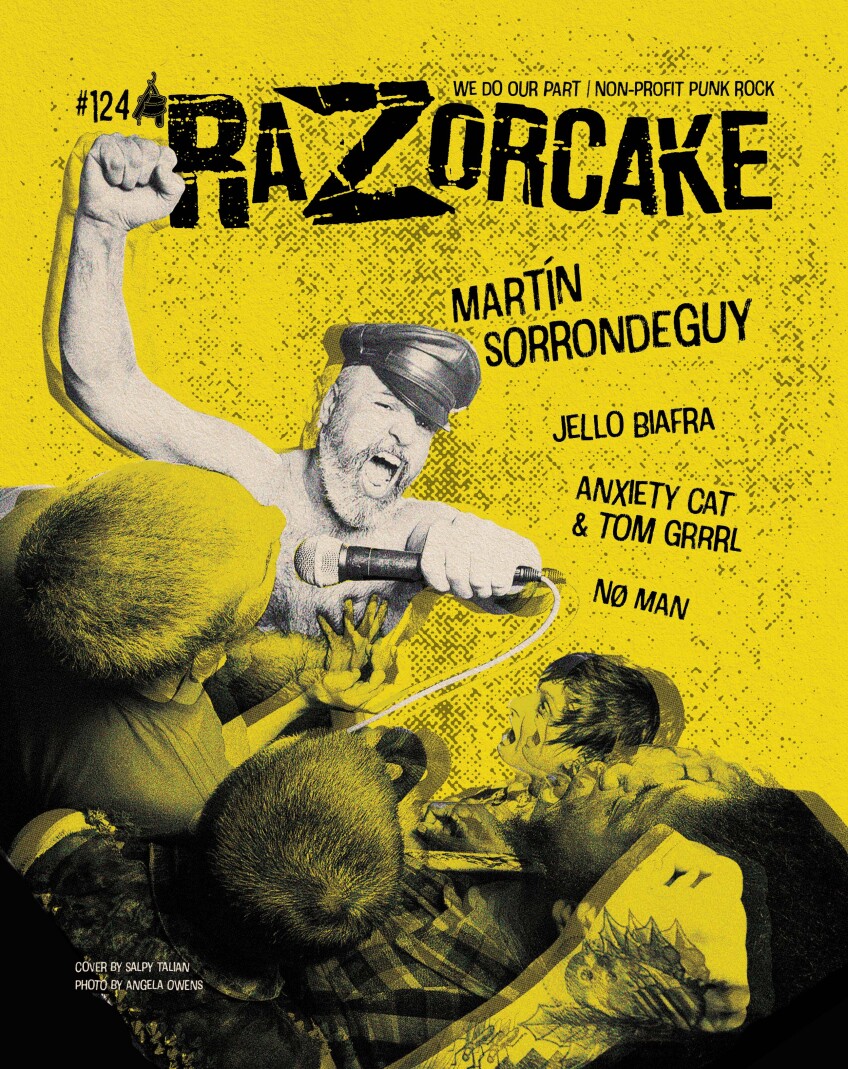

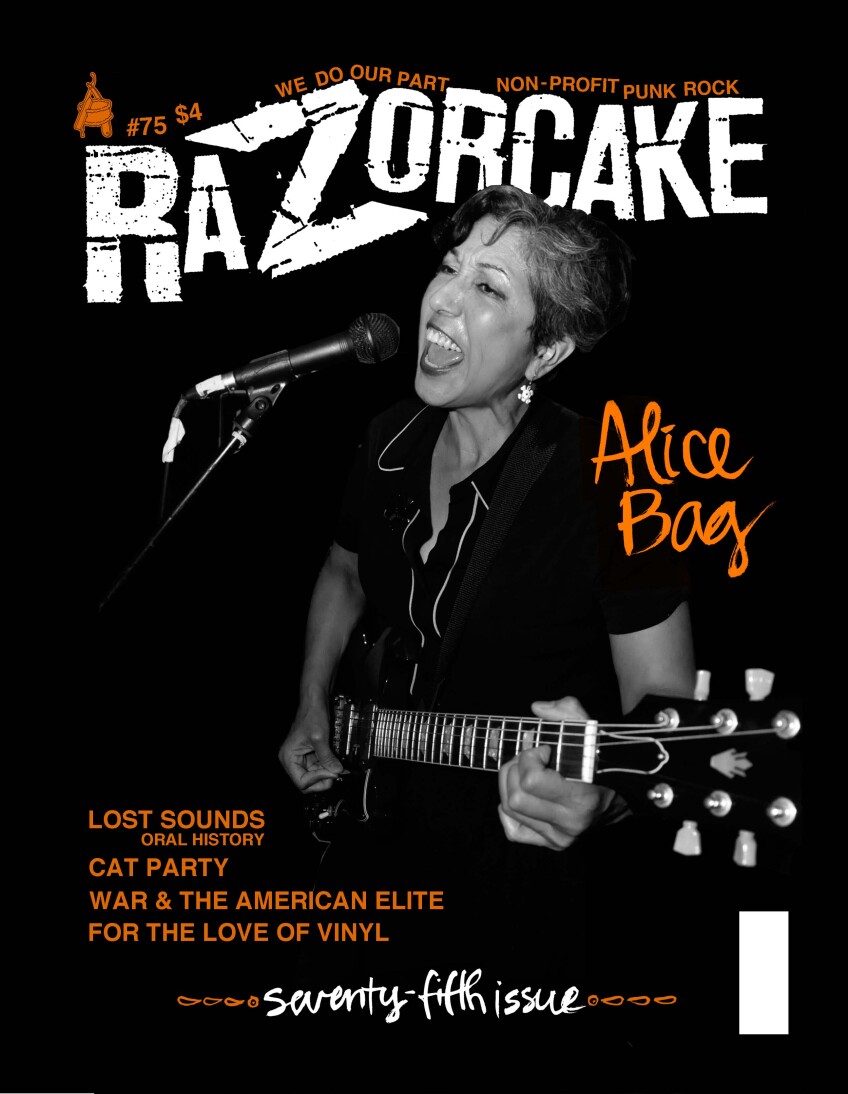

Every two months for the past 21 years, a new issue of "Razorcake" arrives in homes, cafes, record stores and community spaces across the United States. A glossy cover wraps more than 100 pages of newsprint spanning stories, interviews and reviews of punk rock from around the world. Each cover a familiar layout of a black and white portrait of an individual or band, surrounded by a colorful frame announcing the issue's features, issue number and logo: a straight razor closing into a frosting trimmed sheet cake.

In the past 18 months, only three covers featured white men. Regular columns and comics reflect the intersection of punk and daily life: whether a Black man, Chicana, Muslim or transgender person. What might seem like a media response to a national reckoning on race and power is actually an expression of the zine's mission statement: "DIY punk can't be fully captured, understood, or expressed by white men. Diversity makes us a better punk organization. We're encouraging people who are marginalized — by ethnicity, gender, sexuality, class and personal experience — to submit material to 'Razorcake.' Let's work with each other."

In addition to the contributors whose work helps 'Razorcake' with its mission of "amplifying unheard voices," the zine is a platform to showcase experience, work and art by people — and punks — of color.

"Razorcake" is a fanzine — independent media created by fans. The history of punk zines in the United States corresponds with the genre's nascence. Many zines were and are local, reflecting immediate community and place while other zines have tried to cover and reflect national and international trends. "Flipside" was a long-running Los Angeles zine that started in 1977 and folded in 2000. Todd Taylor, "Flipside's" last managing editor, founded "Razorcake," which is now the last nationally distributed, physical zine in the country. When "Razorcake" debuted in 2001, there were a handful other zines in print that could be found nationwide — notably "HeartattaCk," "MAXIMUMROCKNROLL" (or "MRR"), "Profane Existence,""Punk Planet" and "Suburban Voice." "MRR" and "Suburban Voice" still exist, albeit in digital form.

A typical issue of "Razorcake" includes interviews with bands and artists; reviews of music, film and print media; musings from columnists; as well as advertisements that cover the costs of printing and publishing a magazine.

As a non-profit organization, nearly all the work to publish "Razorcake" comes from volunteers, with the exception of co-founders Todd Taylor and Daryl Gussin, who oversee day-to-day operations from Taylor's home in Northeast Los Angeles, otherwise called Razorcake HQ.

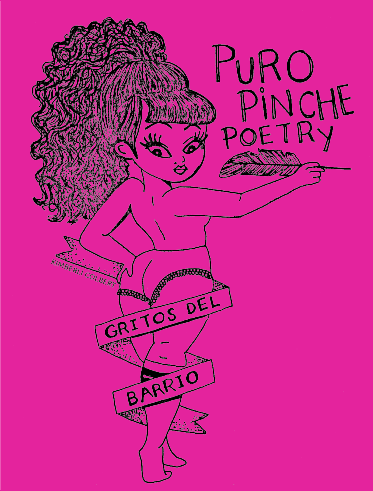

Ever Velasquez & Puro Pinche Poetry

"Everyone is doing their individual project and it's beautiful how it comes together," said Ever Velasquez, who, along with Roque Torres, runs "Razorcake's" poetry section, Puro Pinche Poetry.

Velasquez is a gallery manager and talent scout fo Charlie James Gallery in Chinatown. She began reading "Razorcake" and listening to it podcast more than 15 years ago. She was intrigued by an ad soliciting volunteers. So she started donating her time by making buttons, sorting mail and assisting with podcasts and interviews.

When Donald Trump was elected, Velasquez wanted to channel her anger and emotions in an organized response. That response needed to be art based. After discussion, that meant curating voices from East and Southeast Los Angeles poets and writers. The column is now a regular, recurring poetry section in a zine otherwise dedicated to punk.

It's time to take that power back and do what we have been doing for centuries, creating new possibilities and sharing ideas while staying vigilant and resilient.Ever Velasquez, Puro Pinche Poetry

"It was important to start a poetry page as a tool for the community to desogarse [undrown] about everything going on. I had one line that kept echoing in the back of my head and that was: Language is the tool of the oppressor," she explained via text message. "So, I thought... it's time to take that power back and do what we have been doing for centuries, creating new possibilities and sharing ideas while staying vigilant and resilient."

Puro Pinche Poetry celebrates its fifth anniversary in January.

Michelle Cruz Gonzales & The Spitboy Rule

Michelle Cruz Gonzales stopped saying the pledge of allegiance in third grade. She figures she has lived by DIY punk ethos since. The drummer of influential Bay Area hardcore band Spitboy, Cruz Gonzales is now a professor of English and Creative Writing at Las Positas College in Northern California.

As a writer, her pitches to print and digital publishers weren't getting any traction, even after publishing an autobiography about her life and experience in a feminist, all-women punk band. While writing about Spitboy, Cruz Gonzales realized it is just as important to tell the story of Bitch Fight.

"The first punk rock band in Tuolumne county was women — two women of color — three girls whose moms were on f*****g welfare. That's really important for me to say to people. That's really radical," Cruz Gonzales said. "People are still trying to think punk rock is white dudes and it's not."

During a reading at legendary Berkeley punk venue Gilman, Taylor approached Cruz Gonzales. She recalls being initially leery; another white dude hawking a zine. But she appreciated what she began to read. Taylor had handed her a copy ofissue #75 with her friend and punk icon, Alice Bag, on the cover.

"The Spitboy Rule," Cruz Gonzales' column for "Razorcake," is an opportunity to not only share her stories and experience, but express her full potential as an artist in another form: writing. Some work is personal: a recent essay on watching Bow Wow Wow's Annabella Lwin perform at a "Ladies of the '80s" show. In another column, Cruz Gonzales used script treatment to tell the story of Bitch Fight. The treatment, she explains, signals to readers they are not reading an autobiography. Then there is the fiction, like a conversation between a Bakersfield Chicana and The Clash's Joe Strummer. The story, Cruz Gonzales explains, allowed her to interrogate Strummer about singing in Spanish on "Spanish Bombs."

Jimmy Alvarado & Countering the Narrative

In "Razorcake's" third issue, published in 2001, Jimmy Alvarado published an article that would become a manifesto of sorts Teenage Alcoholics sought to correct the historical record which had neglected a thriving, diverse punk scene in and from East Los Angeles, City Terrace, Boyle Heights and the greater Eastside. The first published oral history of Los Angeles punk had relegated the Eastside scene to less than four pages. Further academic inquiries perpetuated error and inaccuracy. Alvarado, an Eastside punk since 1981, wanted to not only correct the record but highlight the contributions of bands like the Stains, whose work has gone largely unacknowledged.

"The important thing was the information. We were trying to counter the narrative — that was always my intention, to counter the narrative," Alvarado explains.

Countering the narrative led to a broader documentation of the initial waves of Eastside bands who hadn't been recognized or their contributions downplayed. None more evident than "We Were There," a convening of Los Angeles First Wave punks who were Chicano and present in the Hollywood scene. Led by Alice Bag, the gathering of voices was a response to a series of curated exhibits by the Smithsonian on the contributions of Latinos to popular music in the United States.

The interviews published in "Razorcake" are actually transcripts from Alvarado's ongoing documentary project published online as part of "Razorcake's" Eastside Punks video series.

James Spooner: 'It Feels Brown'

James Spooner is a vegan tattoo artist. He is also creator of "Afro-Punk," the 2003 documentary about African-Americans in punk rock, which later spawned a festival of the same name. Fifteen years after making "Afro-Punk," Spooner moved to Highland Park. In a local bookstore, he stumbled upon a copy of "Razorcake." The experience brought back memories of reading"HeartattaCk" and "MRR" as a teenager in New York City after leaving California's Apple Valley, now the subject of Spooner's graphic novel memoir, "The High Desert: Black. Punk. Nowhere."

Spooner had already begun drawing one-cell comics on Instagram. After a Buzzcocks show, Spooner couldn't let go of his annoyance at the band's behavior by waiting for cheers for an encore before finishing their set. So his girlfriend challenged him to turn those feelings into a comic (Issue #112), which was published in "Razorcake." Like the zines' other contributors, Spooner donates his time as an artist through comics and illustrations.

In addition to the encore comic, Spooner has created two full-page, multi-cell comic strips for "Razorcake." Seemingly innocent, his strips talk about bootlace colors and hairstyle. However, within the context of punk, the choice is a statement of race and white supremacy; themes that Spooner has investigated across his creative work. He calls his contributions to "Razorcake" a "cool dip into magazine journalism."

The reflection of Los Angeles and punk communities of color within "Razorcake" is both reassuring here and meaningful for people outside Los Angeles, Spooner says.

"When I read the actual magazine, it feels very Brown," Spooner comments. "But it feels Brown without being specifically Brown, which is probably good for the rest of the country, because then white punks are then introduced to this history and experience."

Making the Implicit Explicit

Punk isn't a monoculture. But much of the historic record — books, photos, documentaries — present punk as a primarily white male experience when that is not the case. New research and personal experience, which has been documented in "Razorcake," is correcting historical omissions. As "Razorcake" founder and editor Todd Taylor has said, showcasing punk's diversity is actually a reflection of the initial wave of punk rock in Los Angeles.

"There's no shortage of stories of people whose stories haven't been told; whose stories were integral to the whole," explains Taylor. "We made the implicit explicit and that's when things fell into place."

There's no shortage of stories of people whose stories haven't been told.Todd Taylor, Founder of Razorcake

While documenting personal experience, "Razorcake" is also creating professional experience, Cruz Gonzales points out. She has marveled at the hive of volunteers in every aspect of production. With a core of about 150 regular contributors, Taylor estimates over 1,000 people have volunteered since they began. That reveals tremendous trust and responsibility in the writing, editing, layout and production, she notes.

"It's a magazine that is actually giving younger people real world experience in a variety of different journalistic mediums," said Cruz Gonzales. "You have people with less experience who write things that are just as interesting because their style is fresh. They're doing really cool work that I value."