Infinite Return: Jenny Yurshansky Traces Her Soviet Jewish Roots

In partnership with The Jewish Federation of Greater Los Angeles: The Jewish Federation of Greater Los Angeles leads the community and leverages its resources to assure the continuity of the Jewish people.

For years, Los Angeles artist Jenny Yurshansky has asked her mom the same question: When will they go back to Moldova?

The small country, wedged between Ukraine and Romania, is part of her family's story. Yet, she's never even seen it.

Yurshansky's mother and father left their home country of Moldova in 1978 during their late 20s. They were headed to Israel, where other relatives had gone, but a family friend mentioned that the U.S. would be more suited to their personalities. They took the suggestion and headed to L.A. Yurshansky was born en route, on an island in the Tiber River of Rome. But for a while, she has wanted to return to Moldova, to find out more about her Jewish immigrant roots and how they relate to her artistic practice. Like many immigrants to the U.S., however, her parents do not want to remember -- or even talk about -- this history.

But Yurshansky is determined to find the truth.

She applied for a $3,000 research grant from Asylum Arts for the project that she is calling "Crusted Memory," which involves: "...looking into the history of the massive 1970s exodus of Soviet Jewish refugees, of which I am a legacy of the wave that left in 1979. Nearly 250,000 Jews were traded for wheat, as part of trade deals with the U.S., SALT I and II," writes Yurshansky in her proposal.

A New York Times opinion piece in 1981, entitled "What is the Price of a Soviet Jew?" lays out the situation: "Without a word of explanation, the Soviet Union is again letting Jews leave in large numbers. It may be only an illusion that Moscow regulates the flow of this human traffic with its expectations of American trade or other reward. But the record of a decade and the newest signal suggest such a correlation -- a purposeful bartering with a people's fate... Just look at the pattern since 13,000 Soviet Jews were unexpectedly allowed to leave in 1971: With the signing of SALT I, the first big wheat deal and the promise of more trade, the number rose in 1972 and 1973 to 32,000 and 35,000." Following the exodus, Yurshansky's family eventually resettled in the San Fernando Valley.

Currently, Yurshansky is most interested in what she describes as the "gaps of memory and information that were experienced within a state where these people were second-class citizens." Ultimately, she wants to answer the question: "How have the losses in cultural memory been manifested?" through this a daunting, if not long-form research project.

But when Yurshansky told her mom, Rima, about these plans for the grant, her mom ignored her.

"And then I got it," Yurshansky said, with her eyes lit up. "I didn't even have to say anything to her. I was just like, 'Mom, guess what!' And she was like, 'Ah, I'm not going.' I didn't even have to tell her what it was related to. She could see it on my face."

In the past, some of Yurshanksy's multimedia work, such as "Blacklisted: A Planted Allegory," has dealt with themes related to migration, borders, and xenophobia. Her upcoming show "The Gloaming," at Visitor Welcome Center, opens April 23, and will feature work from three artists who are immigrants, ruminating on absence and loss.

Yet for her Moldova project, Yurshansky decided to take an approach that is more personal and narrative than anything she's ever done. This project felt like a risk that she was ready to take.

However, she still had to convince her mother that it was worth it.

To talk things out, Yurshansky had a meeting with Abigail Phillips, one of the organizers at Yiddishkayt, a group that arranges trips through the history of Yiddish culture. Their trips travel through Chișinău, Moldova, Romania, and Transylvania before landing in Vienna. Phillips offered Yurshansky and her mother spaces on the trip.

For Yurshansky, this was a dream come true. After a few meetings, her mother eventually warmed up to the idea. The plan was for them to travel to Moldova with a group that includes a cultural ethnographer, cultural anthropologist, other creatives, and a psychiatrist. It wouldn't be the two of them going alone; they would have support from the group, which made a big difference. It's a 10-day trip overseas, departing on May 24 and returning on June 4, 2016.

"[My mother] still is saying that there is no reason for me to go back, for myself, but she saw that it was important for me so she was like, 'I will do it for you,'" says Yurshansky.

For Yurshansky, Moldova is a place of stories and the past -- not a place that she knows or understands first-hand. She knows that it was a tumultuous time for Jews in Eastern Europe when her parents departed the country. Much like Black Americans during Jim Crow South, Jews were given the right to vote, but were considered an ethnic minority and identified as such. This meant that Jews had restricted travel and could only hold certain jobs. Jews could not have government or military jobs, either. If they had higher career aspirations, the bar to entry was nearly impossible.

"My mom Rima wanted to be a doctor," says Yurshansky. "In all practical senses she couldn't be a doctor because you would have to be the top student in your graduating class, to apply to go to med school, to get the position. The quota system made it impossible for Jewish people to do anything."

As an artist and daughter of Jewish immigrant parents, Yurshansky grew up in the Valley, and has had a relationship to Judaism. But her Jewish heritage didn't factor into her identity as much as her parents.

"We didn't have a lot of connection to the Jewish community [in L.A.]," says Yurshansky. "My parents would try by going to religious after-school programs like Chabad, for them to give us a chance to learn about Jewish religious history that they would never have known about, or had access to. It was also up to us to determine how religious to be, which of course I decided later was not useful for me."

Growing up Yurshansky identified with being an immigrant more than a Jew. Her relationship to Judaism was very much bound up in her attendance at Chabad and Jewish religious services, which she described as more of a formality and a way to recognize her ethnic background than an ethnic identity. Her trip back to Moldova with her mother marks a turning point for her -- a sort of coming out as a Jew, as it were.

"It's a 'coming out' of something that I don't know I have full claim over, even though it's completely who and how I exist," says Yurshansky. "It's shaped the whole history and arc of my family and people, but religiously I do not identify that way. If I were to call myself a Jewish artist, the project I'm engaging with is trying to ask a much broader set of questions through this one entry point."

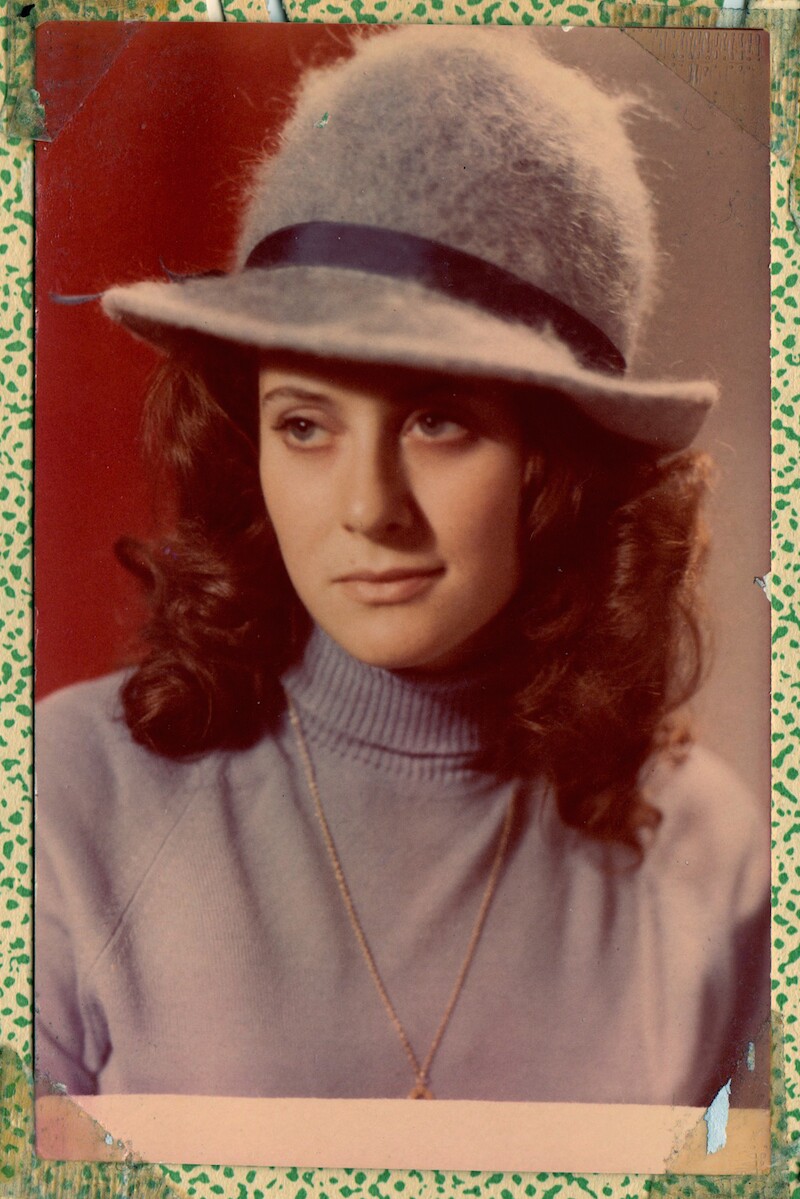

Top image: Jenny Yurshansky, "Blacklisted: A Planted Allegory (Incubation)," 2015.