I Am Armenian: The Intriguing Life of Aurora Mardiganian

As April 24 marks the 100th anniversary of the start of the Armenian Genocide, the spring programming for the Hammer Museum's "I Am Armenian" series focuses on the defining event of 20th century Armenian history. The Genocide essentially marks the beginning of the Armenian diaspora, as the survivors spread throughout the world.

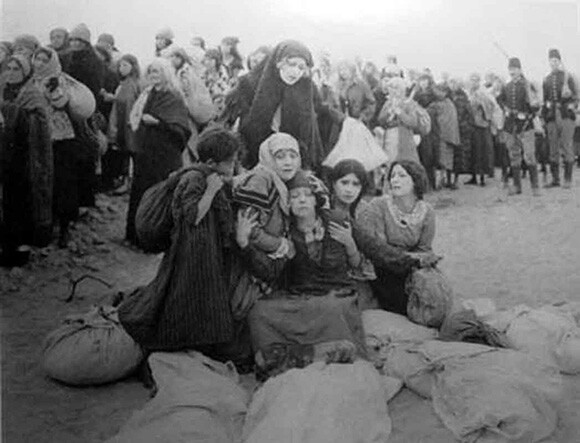

Author Anthony Slide and documentary filmmaker Dr. Carla Garapedian recently presented a talk at the museum about "Ravished Armenia," a silent flick from 1919 based on the story of Armenian Genocide survivor Aurora Mardiganian. Like the majority of films made during the silent era, "Ravished Armenia" is technically lost. All that is known to exist is 20 minutes of badly preserved footage that includes only the heavy-action bits of the movie. Slide, a film historian, theorizes that at some point, the film was cut up to make a documentary of the early 20th century atrocities. There is no known newsreel footage of the events that occurred in Turkey during World War I. This fictional reenactment of the Genocide, he and Garapedian agree, could pass for non-fiction.

Slide is quick to point out that the disappearance of "Ravished Armenia" (also known as "Auction of Souls") isn't the result of a conspiracy. Some might want to draw that conclusion. After all, Turkey continues to deny that the Genocide happened. Silent films, though, didn't stick around after sound was incorporated into the medium. Slide notes that 80 percent of the movies made during the silent era are lost and added that's particular true for "orphan films," which weren't connected to a major studio. In its day, though, "Ravished Armenia" was a blockbuster and, today, the work still holds a lot of significance. It's the first film based on the Armenian Genocide and its star, Aurora Mardiganian, was also its subject.

Throughout the year, the Hammer will feature monthly programming pertaining to the Armenian diaspora. The series, "I Am Armenian," began in January with a screening of "Calendar," from the acclaimed Canadian-Armenian director Atom Egoyan. "'I Am Armenian' reflects on Armenian culture and history but also aims to connect Angelenos with other Angelenos as well as new cultures and ideas," says Claudia Bestor, director of public programming at the Hammer, in a statement to Artbound. The museum team worked closely with Garapedian, who is affiliated with the Armenian Film Foundation.

"One of the criterion was to show things that maybe not everybody has seen and it's directed mainly at the non-Armenian community," says Garapedian. "Although we're getting good participation from the Armenian community, I would say half to maybe 2/3 of the audience is not Armenian at the Hammer events, so we can't assume that they've seen these movies."

Aurora Mardiganian, the woman whose life is at the center of "Ravished Armenia," came to the United States not long after she escaped Turkey. Soon after her arrival, her experience was released as a book, which became a hot seller. "Ravished Armenia," the book, remains in print and is included in "Ravished Armenia and the Story of Aurora Mardiganian," along with a script for the film and an essay by Anthony Slide.

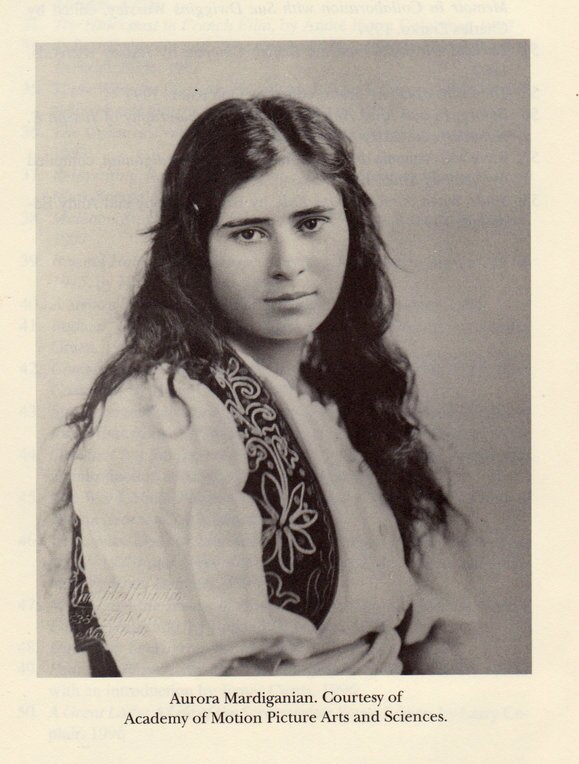

At first, Slide didn't think that Mardiganian was a real person. "I thought she was some sort of phantom of the imagination," the film historian says, a composite character based on the varied experiences of young Armenian women who endured genocide in Turkey. Mardiganian's story, told in the book Ravished Armenia, became the basis for the first film on the atrocity, a blockbuster silent flick that helped raise millions of dollars for the charity Near East Relief. In the book, itself a hot seller after its release in 1918, the tragedies come page after page. Between the torture, murder and sexual violence, it's hard to fathom how one person could have witnessed so much brutality and experienced so much grief.

However, Mardiganian did exist. She was born Arshaluys Mardigian (her name was changed upon moving to the United States) in the early 20th century and was raised in an Armenian family in Turkey. Once in the U.S., Harvey Gates, a screenwriter, and his wife Eleanor Brown Gates became her guardians and essentially orchestrated her brief ascent to fame.

---

Inside his Studio City home, Slide explains how he came to meet Mardiganian. He was working as an editor at the time and had a lot of freedom to what he could publish. He wanted to reprint the book with an essay about how the film came to be. After contacting an Armenian organization, he was able to track down a neighbor of Mardiganian's in New York. The neighbor informed him that the woman had since moved to Los Angeles and was living in Van Nuys. Slide obtained her address and wrote a series of letters that received no reply. Eventually, Mardiganian's son called him and said that Slide could meet her, but the son would have to pick up Slide and take him to the destination.

In 1988, Slide met Mardiganian in a small, Van Nuys apartment."You wouldn't have thought that she was once a movie star," he says. Mardiganian served Armenian coffee and stuffed grape leaves and talked about the movie. "She was thrilled to have someone speak with her because she said that no one had every spoken to her about the film," he says. She gave him the coffee cup when he left the meeting.

During the interview, Mardiganian told Slide that she was paid $15 a week to make the film. As Slide explains in his essay, Mardiganian didn't know what film was. She thought that she would be posing for still photos. Plus, her trauma was quite fresh and the wounds were rubbed open when she saw people dressed in Turkish costumes on set.

"She had been exploited by people," says Slide. "She had been exploited by Harvey Gates, who was one of the men behind the book and the film. She was exploited by the filmmakers. She was exploited by Near East Relief in a way because they were using this film to raise money and to their credit, they raised hundreds of millions of dollars for Armenian relief, but they didn't seem to realize how to treat this young girl. She was just an object, really, to be used."

At this point in time, the Armenian Genocide has become a fashionable cause, a trending topic that fueled the outrage of readers and movie-goers. Filmmakers played up on that. Of the stills that remain from "Ravished Armenia," one depicts a scene where women are crucified. That's not something that actually happened. From later interviews with Mardiganian, the crucifixions is based on something closer to impalement. This image, though, of women on the cross is actually less brutal and heightens the way the Genocide was framed in Western media as a crime committed specifically against Christians.

"The sad reality is that I don't really think that American audiences or European audiences cared very much that it was Armenians involved," says Slide. "They cared that it was Christians. The emphasis is on the Christian."

As public outrage faded, so did Mardiganian fade from their consciousness. As documented in Slide's essay, she sued to obtain some of the money that she should have received for appearances related to the film and went on to live a life off camera. Decades later, she spent the last few weeks of her life at the Ararat Home in the San Fernando Valley and died alone at nearby Holy Cross Hospital. Her body went unclaimed and she was cremated and buried anonymously somewhere in Los Angeles. Slide sees this as "the tragedy" of Mardiganian's life. Certainly, it is a heartbreaking end for someone who had already endured so much pain.

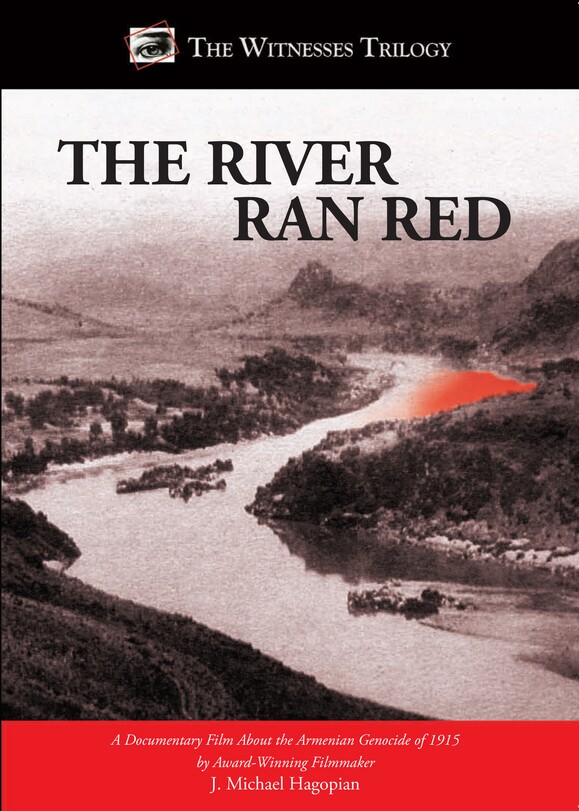

Still, Mardiganian did make an impact on the world. During the Hammer presentation, Garapedian mentions a recent announcement that George Clooney is attached to a new award called the Aurora Prize for Awakening Humanity. The $1 million grant is named in part for Mardiganian and will be awarded to people who risk their own lives to assist the survival of others. Both Garapedian and Slide discuss the continued quest to find a complete copy of the film. Meanwhile, an interview with Mardiganian, filmed in the 1970s by documentarian Dr. J. Michael Hagopian, is part of the Armenian Film Foundation collection that will be added to USC's Shoah Foundation Institute's Visual History Archive.

In the coming months, guests will also have the chance to view Sergei Parajanov's artful depiction of the life of poet Sayat-Nova, "The Color of Pomegranates," and the Fred Astaire and Cyd Charisse vehicle, "Silk Stockings," which was directed by Rouben Mamoulian.