Hysteria, Witches and the Wandering Uterus: A Brief History -- Or Why I Teach "The Yellow Wallpaper"

Terri Kapsalis is a writer, performer and cultural critic. She is also an Adjunct Professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC). For the past two decades, she has been discussing the 6,000-word short story “The Yellow Wallpaper" with undergraduates as part of a course titled "The Wandering Uterus: Journeys Through Gender, Race, and Medicine."

The following is an edited excerpt, which was originally published in the website Literary Hub. It is republished here to give context to the world Vireo inhabits in "Vireo: The Spiritual Biography of a Witch's Accuser," which is now available for streaming. Watch the 12 full episodes.

I teach “The Yellow Wallpaper” because I believe it can save people. That is one reason. There are more. I have taught Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s 1891 story for nearly two decades and this past fall was no different. Then again, this past fall was entirely different.

In our undergraduate seminar at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, we discussed “The Yellow Wallpaper” in the context of the nearly 4,000-year history of the medical diagnosis of hysteria. Hysteria, from the Greek hystera or womb. We explored this wastebasket diagnosis that has been a dumpsite for all that could be imagined to be wrong with women from around 1900 BCE until the 1950s. The diagnosis was not only prevalent in the West among mainly white women but had its pre-history in Ancient Egypt, and was found in the Far East and Middle East too.

It is no accident that [hysteria as] a diagnosis took off just as some of these same women were fighting to gain access to universities and various professions in the U.S. and Europe. A decrease in marriages and falling birth rates coincided with this medical diagnosis criticizing the New Woman and her focus on intellectual, artistic, or activist pursuits instead of motherhood.

The course is titled “The Wandering Uterus: Journeys through Gender, Race, and Medicine.” It gets its name from one of the ancient “causes” of hysteria. The uterus was believed to wander around the body like an animal, hungry for semen. If it wandered the wrong direction and made its way to the throat there would be choking, coughing or loss of voice. If it got stuck in the rib cage, there would be chest pain or shortness of breath, and so on. Most any symptom that belonged to a female body could be attributed to that wandering uterus. “Treatments,” including vaginal fumigations, bitter potions, balms, and pessaries made of wool, were used to bring that uterus back to its proper place. “Genital massage,” performed by a skilled physician or midwife, was often mentioned in medical writings. The triad of marriage, intercourse, and pregnancy was the ultimate treatment for the semen-hungry womb. The uterus was a troublemaker and was best sated when pregnant.

“The Yellow Wallpaper” was conceived thousands of years later, in the Victorian era, when the diagnosis of hysteria hit its heyday. Medical attention veered from the hungry uterus and was placed on a woman’s so-called weaker nervous system. Nineteenth-century physician Russell Thacher Trail approximated that three-quarters of all medical practice was devoted to the “diseases of women,” and therefore physicians must be grateful to “frail women” (read: frail white women of certain means) for being an economic godsend to the medical profession.

At the time, the medical community believed that hysteria, also known as neurasthenia, could be set off by a plethora of bad habits including reading novels (which caused erotic fantasies), masturbation, and homosexual or bisexual tendencies resulting in any number of symptoms such as seductive behaviors, contractures, functional paralysis, irrationality and general troublemaking of various kinds. There are pages and pages of medical writings outing hysterics as great liars who willingly deceive. The same old “treatments” were enlisted to cure these afflictions — genital massage by an approved provider, marriage and intercourse — but some new ones included ovariectomies and cauterization of the clitoris.

It is no accident that such a diagnosis took off just as some of these same women were fighting to gain access to universities and various professions in the U.S. and Europe. A decrease in marriages and falling birth rates coincided with this medical diagnosis criticizing the New Woman and her focus on intellectual, artistic, or activist pursuits instead of motherhood. Such was the downfall of Gilman’s narrator in “The Yellow Wallpaper.”

There’s a good chance you’ve read the story in school, but in case you didn’t or have forgotten, here is a synopsis. Following the birth of her first child, the narrator says she feels sick, but her physician husband has dismissed her complaints as a “temporary nervous condition — a slight hysterical tendency.” He has rented a country house and has put her to rest in the former nursery. She explains,

So I take phosphates or phosphites—whichever it is, and tonics, and journeys, and air, and exercise, and am absolutely forbidden to “work” until I am well again.Personally, I disagree with their ideas.Personally, I believe that congenial work, with excitement and change, would do me good.But what is one to do?

The narrator’s work is that of a writer. She sneaks paragraphs here and there when she is not being observed by her husband or his sister who is “a perfect and enthusiastic housekeeper, and hopes for no better profession.” The story documents the narrator’s frustrations with her so-called treatment and her husband’s resolve that she only needs to exercise more will and self-control in order to get better. “‘Bless her little heart!’ said he with a big hug, ‘she shall be as sick as she pleases.'”

We witness the narrator’s steady decline as she becomes increasingly obsessed with the room’s ghastly wallpaper: “the bloated curves and flourishes — a kind of ‘debased Romanesque’ with delirium tremens — go waddling up and down in isolated columns of fatuity.” Gilman — a prolific writer of fiction, poetry and progressive books, including Women and Economics, a woman who drew large crowds as she made the national lecture circuit in her day — is masterful at showing us how things fall apart for her protagonist. In the final scene of the story, the narrator creeps along the edges of the former nursery amidst shreds of wallpaper, stepping over her crumpled husband who has fainted upon discovering his wife in such a state.

A number of 19th-century practitioners gained fame as hysteria doctors. S. Weir Mitchell, a prominent Philadelphia physician, was one of them. He championed what he called “the rest cure.” Sick women were put to bed, ordered not to move a muscle and instructed to eschew intellectual or creative work of any kind, fed four ounces of milk every two hours, and oftentimes required to defecate and urinate into a bedpan while prone. Mitchell was so renowned he had his own Christmas calendar.

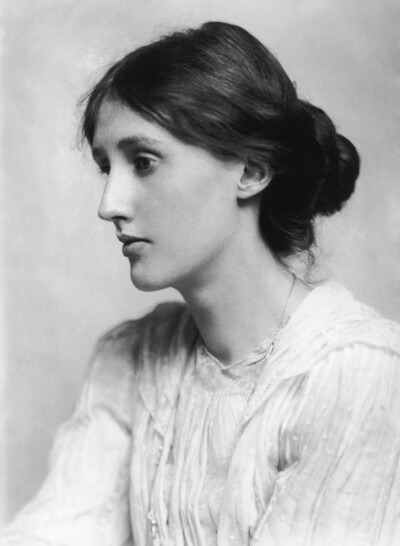

Mitchell was Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s physician. His rest cure was prescribed to some of the great minds of the time, including Edith Wharton and Virginia Woolf. Scores of white women artists and writers were diagnosed as hysterics in a period when rebelliousness, shamelessness, ambition and “over education” were considered to be likely causes. Supposedly, there was too much energy going up to the brain instead of staying in the reproductive organs and helping the female body do what it was supposed to do. As Mitchell wrote, “The woman’s desire to be on a level of competition with man and to assume his duties is, I am sure, making mischief, for it is my belief that no length of generations of change in her education and modes of activity will ever really alter her characteristics.”

Transgressing prescribed roles was thought to make women sick. British suffragettes, for instance, were “treated” as hysterics in prison. Outspoken proponents for women’s rights were often characterized as the “shrieking sisterhood.” In our seminar discussion, we make the comparison to the numbers of African American men diagnosed as schizophrenics at a State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Ionia, Michigan during the 1960s and 70s, as documented in psychiatrist Jonathan Metzl’s powerful book “The Protest Psychosis: How Schizophrenia Became a Black Disease.” A diagnosis can be a weapon used as a way to control and discipline the rebellion of an entire demographic.

As we discussed “The Yellow Wallpaper” and its historical context, I could see that one of my students, Allie, was becoming more and more outraged. She looked as if she might bolt from her classroom seat. Her hand shot up, “Would you believe that my high school English teacher told us, ‘If this woman had followed her husband’s instructions, she wouldn’t have gone crazy?!'”

If I’d had a mouth full of something, I would have done a spit take. In all my years of teaching the story, I cannot remember ever hearing this jaw-dropping explanation. But Allie opened the floodgates. Another student, Bec, raised her hand, “We read it in eighth grade. We were all concerned and confused, especially the girls. And disturbed by the ending. No one understood what was wrong with the woman. The story didn’t seem to make any sense.”

Max added, “In my A.P. Psychology class, our teacher asked us to use the DSM 4 to diagnose the woman in “The Yellow Wallpaper.” I remember a number of student guesses, like Major Depressive Disorder, General Anxiety Disorder, as well as OCD, Schizophrenia, and Bipolar with Schizotypal tendencies.”

Noëlle said she remembered a fellow high school student describing the narrator as “animalistic” and the teacher writing it on the board. There was no discussion of what “hysteria” actually meant.

Keeta encountered the story in a college literature seminar titled “Going Mad.” That class discussion focused on the “insane and unreliable narrator." “[It was] a missed opportunity for me to learn about something very real and current, and in some ways I feel wronged by that,” Keeta said. They explained that they had a similar feeling when watching the film “Beloved” in middle school. “Here’s your heritage, and it’s dumped in your lap, and you have no idea why this enslaved woman killed her child. If you had more information about the history of slavery and reproductive resistance, then you would be able to make better sense of what you were seeing.”

Cristina hadn’t read “The Yellow Wallpaper” before but said, “In the fourth grade in my all-girls Catholic school in Bogotá, my religion teacher told the class that we should only show our bodies to our husbands and doctors. Meaning they are the only ones that can touch our bodies. I think there is some connection here, no?”

I am always moved by the associations students make between the history of hysteria and their own lives and circumstances. We discussed how it is startling to learn about nearly four millennia of this female double bind, of medical writings opining cold, deprived, frail, wanting, evil, sexually excessive, irrational and deceptive women while asserting the necessity of disciplining their misbehaviors with various “treatments.”

“What about Hillary?” Bec chimed in.

This wasn’t just any fall semester. There couldn’t have been a more appropriate time to consider the history of hysteria than September 2016, the week following Hillary Clinton’s collapse from pneumonia at the 9/11 ceremonies, an event that tipped #HillarysHealth into a national obsession. Rudolph Giuliani said that she looked sick and encouraged people to google “Hillary Clinton illness.” Trump focused on her coughing or “hacking” as if the uterus were still making its perambulations up to the throat.

For many months, Hillary had been pathologized as the shrill shrew who was too loud and outspoken on the one hand, and the weak sick one who didn’t have the strength or stamina to be president on the other. We discussed journalist Gail Collins’ assessment of the various levels of sexism afoot in the campaign. On the topic of Hillary’s health, Collins wrote, “This is nuts, but not necessarily sexist.” We, in the Wandering Uterus class, wholeheartedly disagreed. But, back in September, we did not understand how deeply entrenched these sinister mythologies had already become.

To help us understand what we were witnessing unfold during the campaign, we turned to prevailing wisdom in the Middle Ages. By way of the church, the myth flourished that women were evil. Women were seen as lascivious and deceptive by nature. Female sexuality, once again, was the problem. So-called witches were accused of making men impotent; their penises would “disappear” and it was claimed that witches would keep said penises in a nest in a tree. Unholy spirits were the cause of bewitchment, a condition that sounded a lot like earlier descriptions of hysteria. Its “treatment” led to the death of thousands of women. In their 1973 groundbreaking treatise, “Witches, Midwives, and Nurses: A History of Women Healers,” Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English argue that the first accusations of witchcraft in Europe grew out of church-affiliated male doctors’ anxieties about competition from female healers. The violence promoted by the church allowed for the rise of the European medical profession.

How could we not compare the campaign season to the witch-hunts when folks at rallies started chanting “hang her in the streets” in addition to the by-then familiar “lock her up.” In short order, we witnessed a shift from the maligned diagnosis of a single individual to an all-out mass hysterical witch-hunt against [Hillary Clinton,] a woman who dared to run for presidential office.

In class, we continued to discuss the construction of she-devil, foul-mouthed Crooked Hillary who extremists berated with hashtags like #Hillabeast and #Godhilla and #Witch Hillary. How could we not compare the campaign season to the witch-hunts when folks at rallies started chanting “hang her in the streets” in addition to the by-then familiar “lock her up.” In short order, we witnessed a shift from the maligned diagnosis of a single individual to an all-out mass hysterical witch-hunt against a woman who dared to run for presidential office. We discussed the brilliant literary critic Elaine Showalter whose book “Hystories,” written in the 1990s, focuses on end-of-the-millennium mass hysterias. Prior to the existence of social media, Showalter presciently wrote, “hysterical epidemics. . . continue to do damage: in distracting us from the real problems and crises of modern society, in undermining a respect for evidence and truth, and in helping support an atmosphere of conspiracy and suspicion.”

We discussed the fact that social media had enabled this rapid circulation of Hillary mythologies. I explained that the witch-hunts in Early Modern Europe happened to correspond to the invention of the social media of their day. First published in 1486, “Malleus Maleficarum” (translated as “The Hammer of Witches”) by Reverends Heinrich Kramer and James Sprenger became the ubiquitous manual that spread the church’s methods of identifying witches through questioning and torture in large part by means of the contemporaneous invention of the printing press. For nearly two centuries, this witch handbook was reprinted again and again, disseminating sentences -- such as “She is an imperfect animal who always deceives” and “When a woman thinks alone, she thinks evil” -- that would later inspire the anti-Hillary playbook.

By midterm presentations, we talked about the ways in which hysteria had gone viral with other women candidates, like Zephyr Teachout, a law professor and activist running for Congress, who found herself on the receiving end of attack ads that featured a close-up of her face with a red-lettered CRAZY stamped on it.

Upon closer investigation, this form of political slander was not limited to the current election season or the US. In Poland, women who marched against a recent abortion ban were called feminazis, prostitutes, whores, witches and crazy women. While in 2013, Russian news reports suggested that members of the band Pussy Riot were “witches working with a global satanic conspiracy” in cahoots with the Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.” That should have been a clue to what would follow.

During the weeks running up to the election we veered from the topic of hysteria and discussed the history of gynecology and enslaved women as experimental subjects, sexual anatomy and disorders of sexual development, and queer and trans healthcare, but we still began each class by sharing recent developments from the campaign trail: Muslim registries, pussy grabbing/sexual assault and bullying. We discussed Trump’s remarks that soldiers living with PTSD are not “strong enough,” echoing medical and military attitudes from the previous century that associated male hysteria with WWI and “shell shock.”

The Sunday before the election, I was invited by students belonging to the school feminist group, Maverick, to meet at the Hull-House Museum. We sat on the floor of Jane Addams’ bedroom which houses her 1931 Nobel Peace Prize as well as her thick FBI file, evidence of the one-time moniker “most dangerous woman in America.” We talked about the founding of the Settlement House, that Addams knew that “meaningful work” was important for this first generation of white women that had received a college education. At the Hull-House, Addams and other young women residents worked together with some of the poorest immigrants to improve living conditions, to promote child labor laws, to build playgrounds. They celebrated various immigrant traditions over large shared meals and Italian opera and Greek tragedy.

I told the group that Charlotte Perkins Gilman visited the Hull-House on a number of occasions. It was at the Hull-House that she developed some of her ideas about women and economics, about group kitchens and shared domestic responsibilities. I told them how amazed I was to learn that, as a young woman, Addams, as well as a number of Hull-House residents, had also been under the care of the famed Dr. Mitchell.

I read them excerpts of Addams’ writings during WWI when she was blacklisted for her promotion of peace; her health failed, and she hit the depths of depression. Remarking on her colleagues’ suffering, she wrote: “The large number of deaths among the older pacifists in all the warring nations can probably be traced in some measure to the peculiar strain which such maladjustment implies. More than the normal amount of nervous energy must be consumed in holding one’s own in a hostile world.”

A good deal of the election’s fake news had been dependent on the power of a nearly 4,000-year-old fictional diagnosis.

When our class met two days following the election, we talked about deportations, anti-Muslim hate crimes, LGBTQ vulnerabilities and climate change. A number of us confessed that we were physically ill as we watched the returns come in. I mentioned one friend who wrote me that he felt as though he were drinking poison. Two other friends were struck down by bouts of diarrhea and dry heaves on election night. When they went to their doctor, she said that she had seen an inordinate number of sick people. Something was going around.

For many of these students, the election results were just an added stress to that long-time civil war back home, to having undocumented family, to losses from gun violence or to being targeted when walking down the street because of race and/or gender presentation and/or sexuality and age. For some of us, this next administration would be yet another thing to get through. For more of us, we were only beginning to understand that our democracy and our rights were fragile things.

I didn’t tell them that I was waking up each morning feeling nauseated, my belly distended. I knew I was clenching my gut as if I had been sucker-punched. This clenching plus many surges of adrenaline had set off an old familiar pain in my gallbladder area. A friend told me about his neck pain. Another said her hip pain had returned. I was reminded of Showalter again: “We must accept the interdependence between mind and body and recognize hysterical syndromes as a psychopathology of everyday life before we can dismantle their stigmatizing mythologies.” Who could ever claim that mind-derived illness is not true illness? Pain is not fiction.

The readings for the class immediately following the election included Byllye Avery on her creation of the National Black Women’s Health Project. She wrote about the importance of really listening to each other, that issues like infant mortality are not medical problems, they are social problems. We also discussed an excerpt from Audre Lorde’s “The Cancer Journals.” Her words are remarkably fresh some 30 years later: “I’ve got to look at all my options carefully, even the ones I find distasteful. I know I can broaden the definition of winning to the point where I can’t lose. . . We all have to die at least once. Making that death useful would be winning for me. I wasn’t supposed to exist anyway, not in any meaningful way in this fucked-up white boys’ world. . . Battling racism and battling heterosexism and battling apartheid share the same urgency inside me as battling cancer.” We took heart in Lorde’s reference to, “The African way of perceiving life, as experience to be lived rather than as a problem to be solved.”

Our syllabus continued to portend current events even though it had been composed back in August before the start of the semester. At the escalation of the Standing Rock water protectors’ protests, we discussed Andrea Smith’s “Better Dead than Pregnant,” taken from her book “Conquest: Sexual Violence and American Indian Genocide.” This chapter discusses how the violation of indigenous women’s reproductive rights is intimately connected to “government and corporate takeovers of Indian land.” We discussed Katsi Cook’s “The Mother’s Milk Project” and the notion of the mother’s body as “first environment” in First Nations cultures, which led environmental health activists to the understanding that “the right to a non-toxic environment is also a basic reproductive right.”

“For some of us, this next administration would be yet another thing to get through. For more of us, we were only beginning to understand that our democracy and our rights were fragile things.”

The week the students were to begin their final presentations, we discussed the Comet Ping Pong Pizza conspiracy, that a man actually stormed a DC pizza parlor with an assault weapon because of fake news claiming that this establishment was the locus of Hillary’s child sex slave ring. I would not have been surprised if the fake news writers had taken inspiration from the “Malleus Maleficarum” and reported that the parlor also served Hillary the blood of unbaptized children.

Emma said she was tired of Facebook and where was the best place to get news?

A good deal of the election’s fake news had been dependent on the power of a nearly 4,000-year-old fictional diagnosis. Both news and medical diagnosis masquerade as truth, but they were far from it. How can we make sense of this fake diagnosis in relation to the idea that illness can be born from our guts and hearts and minds? Is there anything truer? And yet, psychosomatic illness continues to be deemed an illegitimate fiction.

We know that the social toxins of living in a racist, misogynist, homophobic, and otherwise economically unjust society can literally make us sick, and that sickness is no less real than one brought on by polluted air or water.

We know that the social toxins of living in a racist, misogynist, homophobic, and otherwise economically unjust society can literally make us sick, and that sickness is no less real than one brought on by polluted air or water. In actuality, both social and environmental toxins are inextricably intertwined. The very people subject to systemic social toxins (oppression, poverty) are usually the same folks impacted by the most extreme environmental toxins. And the people who point fingers and label others “hysterical” are the ones least directly impacted by said toxins.

Then there are the lies leveled at fiction. What of the fake criticism my students had encountered during their former studies of “The Yellow Wallpaper”? Our histories provide us with scant access to the so-called hysteric’s words or thoughts. But Gilman was outspoken about her experience. She wrote about it in letters, in diaries, in the ubiquitous “The Yellow Wallpaper” and in a gem of a 1913 essay titled “Why I Wrote ‘The Yellow Wallpaper.'” In this 500-word piece -- required reading for anybody assigning ”The Yellow Wallpaper” -- Gilman describes her experience with a “noted specialist in nervous diseases,” who, following her rest cure, sent her home with the advice to “‘live as domestic a life as far as possible,’ to ‘have but two hours intellectual life a day,’ and ‘never to touch pen, brush, or pencil again’ as long as I lived.” She obeyed his directions for some months, “and came so near the borderline of utter mental ruin that I could see over.” Then she went back to work—”work, the normal life of every human being; in which is joy and growth and service”—and she ultimately recovered “some measure of power” leading to decades of prolific writing and lecturing. She explains that she sent her story to the noted specialist and heard nothing back. The essay ends.

"But the best result is this. Many years later I was told that the great specialist had admitted to friends of his that he had altered his treatment of neurasthenia since reading 'The Yellow Wallpaper.'

It was not intended to drive people crazy, but to save people from being driven crazy, and it worked."

I teach “The Yellow Wallpaper” because it is necessary to know and to revisit. I teach “The Yellow Wallpaper” because a deep consideration of this story in relation to its historical and medical context teaches us how much more we can learn about every other narrative we think we already know, be it fact or fiction.

Top Image: A clinical lesson about hysteria held at hospital of la Salpêtrière in Paris by French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot | Wikimedia