Hysteria and Surrealism: How a Nearly-Forgotten Mental Patient Inspired Surrealism

Vireo, the groundbreaking made-for-TV opera, is now available for streaming. Watch the 12 full episodes and dive into the world of Vireo through librettos, essays and production notes. Find more bonus content on KCET.org and LinkTV.org.

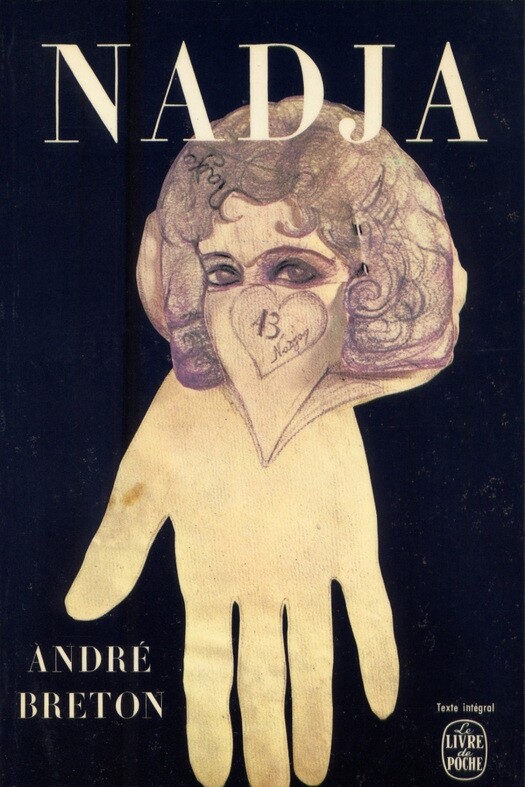

Hysteria and surrealism may appear to have little in common – one is a now-outdated, catch-all diagnosis applied mostly to females highlighted in the innovative opera "Vireo: The Spiritual Biography of a Witch’s Accuser," while the other describes a cultural movement that would inspire a cadre of writers and artists such as Joan Miró, Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, just to name a few. In the early 20th century, their paths converged in the story of “Nadja,” published in 1928 and written by one of the founders of the surrealist movement, André Breton.

In the late 19th century, the bourgeoning medical fields of neurology and psychology overlapped. Western medicine as we understand it today was itself still evolving and scientists who studied the brain and nervous system began asking interesting questions about whether the root of certain afflictions were physical or emotional. One of these so-called ailments was hysteria.

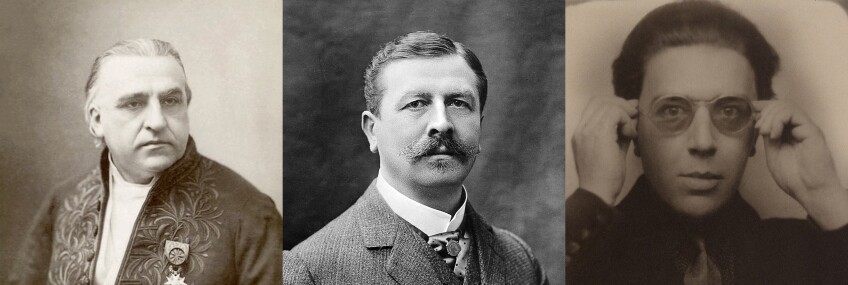

Before being a synonym for something incredibly funny, "hysterical" denoted irritability, anxiety, fainting spells, insubordination, displays of extreme emotion and almost anything that signaled a person's transgression from normative codes of behavior. The definition of the now-colloquial term was in a state of constant flux, as were so-called "cures." Toward the end of the 19th century, perspectives on hysteria evolved further, thanks to the studies of a renowned French physician, Jean-Martin Charcot (1825–1893) and his heirs in science, one of whom was Breton.

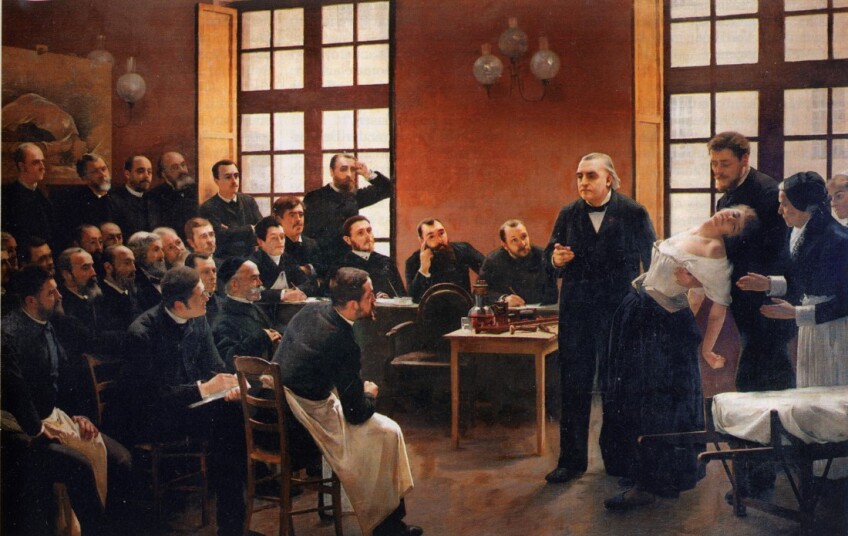

Charcot established the world's first neurology clinic at the Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris in 1882. His long list of achievements include identifying multiple sclerosis, investigating the causes of cerebral hemorrhages and supplying fundamental studies towards the understanding of Parkinson's disease. He was also interested in the origins of hysteria, and along with his student Joseph Babinski (1857-1932), devoted a great deal of time towards the study of the so-called disorder.

Sigmund Freud also studied with Charcot, just one of many students who observed a portion of the father of neurology's three decades of medical research at the hospital. As a result of Freud's observations of Charcot's work, the definition of hysteria morphed from a physical affliction to a psychological one, as outlined in Freud's 1895 publication, “Studies on Hysteria,” co-authored by pioneering neurophysiologist Josef Breuer.

But it was Breton, a would-be physician studying under Babinksi, who recognized the implications of hysteria as a creative force. In 2012, a trio of academics examined the influence of science on art in a study called “Neurology and surrealism: André Breton and Joseph Babinski.” The authors established a direct relationship between Babinski and Breton. They suggested that Breton traded science for surrealism after not only abandoning medical studies because of Babinski, but applying his own observations on hysteria in his definition of surrealism as well.

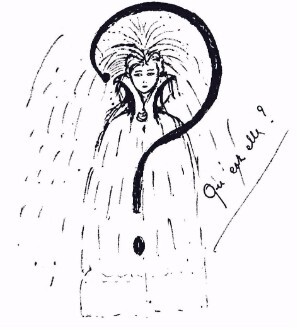

Breton met the woman who would manifest the defining characteristics of his budding cultural movement and inspire the book “Nadja” in 1926. Their encounter is chronicled in the text, which is equal parts autobiographical narrative and stream-of-consciousness Q&A between the author and himself. It begins with the simple question, "Who am I?" The query serves as a response to a drawing by the mysterious Nadja, who asks similarly, "Qui est elle?"

Who is she?

A series of auctions in the early 2000s included dozens of letters addressed to Breton that tied Nadja's identity to that of Léona Delcourt, who was born in 1902 in the suburbs of French Flanders on the border of Belgium. Coming from a financially-stable family, Delcourt exhibited an independent streak when, as a pregnant teen, she refused to marry her lover. Still practically a child herself, she had a daughter in 1920. Delcourt’s parents supported her move to Paris in 1923 while Delcourt's own child remained behind. Within a few years, Delcourt and Breton would meet face-to-face.

"Suddenly, perhaps still ten feet away, I saw a young, poorly dressed woman walking toward me, she had noticed me too, or perhaps had been watching me for several moments," Breton writes in “Nadja,” as translated into English by Richard Howard in 1960. "She carried her head high, unlike everyone else on the sidewalk. And she looked so delicate she scarcely seemed to touch the ground as she walked."

Following their chance encounter, "Nadja" spends ten days with Breton, who is captivated by her ethereal charm as well as her innate ability to translate her own thoughts into symbolic sketches that are included in the publication of the book.

"Before we met, she had never drawn at all," Breton writes, noting that Delcourt’s artworks "belong to that taste for searching in the folds of material, in knots of wood, in the cracks of old walls, for outlines which are not there but which can readily be imagined."

The author continues to watch and study the enigmatic Delcourt: "I have taken Nadja, from the first day to the last, for a free genius, something like one of those spirits of the air which certain magical practices momentarily permit us to entertain but which we can never overcome," he writes.

But soon, Breton distances himself from his unlikely muse, and not long after, Delcourt is admitted to a mental hospital with vague symptoms of “hysteria.” Breton foreshadows their separation in “Nadja”: "About to leave her, I want to ask one question which sums up the rest, a question which only I would ever ask, probably, but which has at least once found a reply worthy of it. 'Who are you?' And she, without a moment's hesitation: 'I am the soul in limbo.’"

In the book, the first-person narrator likens his existence to a specter with an unknown purpose. But how many of the spiritually-tinged existential questions in “Nadja” originated with Breton, and how many came from Delcourt? There’s a technical tone in the book that is discordant with Breton’s cosmological rhetorical questions and eventually, the work evolves from a public epistle to a diary-like reflection on absence and residual memory — specifically, memories of Delcourt, who passed away in 1940 from cancer, never once receiving a visit from Breton during her confinement.

Dutch writer Hester Albach mined the newly uncovered information to write a biographical novel about Delcourt called “Léona, héroine du surréalisme,” (“Léona: Heroine of Surrealism”), which — just like Delcourt's French wikipedia page — doesn't yet appear to be translated into English.

Breton, meanwhile, used Delcourt’s life as an example of how to purely and instinctually represent forces that are beyond the scope of understanding. This idea was a central tenet in surrealism, which typically featured strange, whimsical elements as well as unexpected contrasts and seemingly illogical conclusions. Eventually, surrealism expanded to infiltrate not just art and literature, but the worlds of film, theatre, and music. But few are aware of the impact that the relationship between Breton and Delcourt had on the movement itself, until now.

Top Image: Left: Portrait of Jean-Martin Charcot, circa 1880 (NIH/U.S. National Library of Medicine); Center: Joseph Babinski, circa 1910 (Photograph by Eug. Pirou, Paris); Right: Andre Breton in 1924 / WikiCommons