"How to Read El Pato Pascual": Latin America's Dialogue with Disney

This is produced in partnership with Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, a far-reaching and ambitious exploration of Latin American and Latino art in dialogue with Los Angeles.

In 1941, as America hovered on the brink of war, President Franklin Roosevelt recruited a cute, charismatic 13-year-old to help in the fight against fascism in South America. The new recruit literally fell short in a few categories: age, size, experience.

But what he lacked in physical stature, he made up for in outsized personality.

“Mickey (Mouse) was already extremely popular” worldwide, explained filmmaker and writer Jesse Lerner, so it made sense to use Mickey and the other cartoon critters created by animator Walt Disney to reach Latin American audiences. “It wasn't starting from square one, but rather building on an existing infrastructure (or) tool palette.”

More than 75 years later, Mickey's impact can be felt in the group exhibition “How to Read El Pato Pascual: Disney's Latin America and Latin America's Disney,” curated by Lerner and artist Rubén Ortiz-Torres. It's part of the Getty's Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA collaborative project.

Featuring 150 works by 48 Latino artists, “How to Read El Pato Pascual” opened Sept. 11 and runs through Jan. 4, 2018, at the MAK Center for Art and Architecture at the Schindler House and the Luckman Fine Arts Complex at CSU Los Angeles.

“You'll see a variety of different approaches, from documentary photographers … to performance artists, experimental filmmakers, painters and sculptures,” Lerner said. Featured works range from “Paloma Negra,” a painting by Mexican artist José Rodolfo Loaiza Ontiveros that finds Frida Kahlo tossing back drinks with Cinderella, Belle and Snow White, to Mexican painter Columbian sculptor NadinOspina's “Siameses Aureolados,” which interprets Mickey as a two-headed Pre-Columbian artifact.

Lerner and Ortiz-Torres, a visual arts professor at UC San Diego, first delved in Disney's influence in their 1995 movie “Frontierland/Fronterilandia,” which examines cross-pollination between the United States and its neighbors to the south. (The pair revisited that subject as the curators of “MEX/LA: Mexican Modernisms in Los Angeles 1930-1985” at the Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach in 2011.)

“You can't walk around downtown Mexico City for more than a couple minutes before seeing (a Disney icon),” explained Lerner, a professor of media studies at Pitzer College in Claremont. “Those characters really have a presence in Latin American popular culture.”

Although Mickey and his cartoon pals – Donald Duck, Goofy and the rest – have been a part of the cultural conversation in Central and South America from the beginning, Disney's influence in the region got a huge boost on the eve of America's entry into World War II.

Hoping to curb the influence of Nazis and fascists south of the border, the U.S. government sought to promote Pan-American friendship as part of Roosevelt's Good Neighbor policy. Hollywood celebrities sallied forth for visits. And movie studios – making up for decades of tone-deaf depictions of Latin Americans as lazy peasants and sinister banditos – sought to infuse Latin-American themes into their films.

In 1941, the Roosevelt administration sent Disney and 15 of his employees on a research trip-cum-goodwill tour of Argentina, Brazil and Chile. The result was two animated feature films – “1942's “Saludos Amigos” and 1944's “The Three Caballeros” – as well as several shorts.

Part travelogue, part polemic, the movies find Donald Duck and other familiar Disney figures exploring Latin America's vast and varied cultural terrain with the help of new characters such as José Carioca, a cigar-smoking Brazilian parrot, and Panchito Pistoles, a pistol-packing rooster from Mexico.

The movies were “designed to play to many audiences, so an Anglo audience … who doesn't have a lot of exposure (to) or knowledge about Latin America learns a little something without feeling like they're being lectured to,” Lerner said. “And Latin Americans who are more familiar with the landscape and the cultural context that's being represented are also entertained but not offended. There's this spirit of sharing.”

The sinister side of that cross-cultural pollination is revealed in the controversial classic “How to Read Donald Duck” (“Para leer al Pato Donald”), first published in Chile in 1971. Looking at popular culture through a Marxist, post-colonial lens, Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart critique Disney comics as vehicles for American imperialism.

“For a lot of our artists, that was an important point of reference,” Lerner said.

San Francisco artist Enrique Chagoya, an art professor at Stanford University, encountered “How to Read Donald Duck” as an economics student in Mexico. The text, he recalled, cast the comics he read on Sundays in a disturbingly different light.

“That book was a bridge between my ideas of the economy and my ideas of what a corporate culture like Disney might represent,” Chagoya said.

Starting in the early 1990s, the artist began to infuse Disney elements into his work – reimagining then-President Ronald Reagan as a graffiti-painting Mickey Mouse, hapless puppet Pinocchio or the overwhelmed “Sorcerer's Apprentice” from “Fantasia.”

“I didn't want to represent (Reagan) as a monster. The easiest thing to do in satire is to represent characters that are fanatical, that are very damaging to society … as monsters,” Chagoya explained. “Reality is way more complicated.”

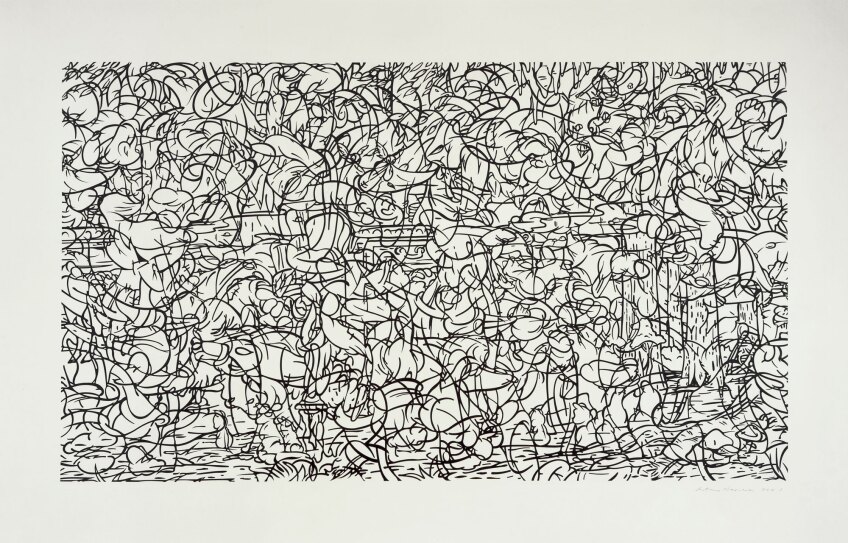

Mickey pops up alongside Superman and Wonder Woman in Chagoya's “Tales of the Conquest: Codex” in 1992. In one scene, he gapes, aghast, at priests with hatchets buried in their heads; in another, the red-handed rodent rides alongside Batman and a camouflaged soldier in a blood-splattered tank, guns aimed at Aztec warriors armed with arrows.

That mouse may look like Mickey but “it's not the harmless cartoon I grew up with,” Chagoya explained. “In my work, it becomes a symbol of Western culture dominating non-Western culture.”

In the same way, the Pre-Columbian people seen devouring severed limbs in Chagoya's 1994 painting “The Governor's Nightmare” parody misconceptions about modern-day immigrants. (Nearby, a bound Mickey lies on a plate as a slavering god brandishes a giant salt shaker.)

“They are the cannibals, the savages, the ones who cross the border and bring illness,” explained the artist, who took his inspiration from former California Governor Pete Wilson and his anti-immigrant policies. “It's a clash of the stereotypes.”

Following the lead of marketers who use childhood nostalgia to sell products to grownups, Los Angeles artist Jaime Muñoz uses Disney characters to explore global power struggles. “Mickey is, to me, a symbol of American capitalism,” said the artist, drawing on his background in commercial art. “When you think of globalism and imperialism, you also think of Mickey.”

While his painting “Fin” imagines an end to that dominance – it features a prone Mickey surrounded by stylized flowers – another piece speaks to the possibility of subverting the socioeconomic structure. “Boing!” features a smiling yet defiant Donald with his fist raised in “a universal gesture for progress,” Muñoz said, signifying the value of “truly participating in your democracy instead of being a spectator.” “It really speaks to our times right now.”

“Boing!” the Mexican-American artist explained, refers to Mexican soft drink maker Pascual Boing, which became a worker-owned cooperative in 1985 following a series of brutal labor disputes. Just as those workers turned their cartoon duck logo – now a shaggy, streetwise version of Donald Duck – into a symbol of freedom, Muñoz seeks to subvert images and manipulate their meaning.

“I see it as reprogramming,” he explained. “Whatever I see as false in the (original imagery), I'll try to change and make it true.”

A similar sense of reinvention guides Irvine artist Mariangeles Soto-Diaz. As a girl growing up in Venezuela, she first encountered Disney in the form of a record featuring stories about Bambi, Dumbo and a super-sized litter of dogs. (“Why Dalmations? Why 101 and not 100?” she remembers musing.) “It was much later than I came in contact with … Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty, the more classic princess stories (about women) whose lives revolve around romantic interests,” she recalled.

“These stories of young, fair-skinned women who need to be rescued by a prince to go live in a castle seemed to insult the intelligence of most of the independently minded professional women I knew, including my mom,” Soto-Diaz said.

Her installation “Painting With Fire” “reimagines an alternative narrative of princess Elena, the first Latina princess created by Disney,” she said. But unlike Ariel in “The Little Mermaid” or Elsa in “Frozen,” the “bold, adventurous and fierce” Elena of Avalor was introduced to audiences in 2016 via a television show, not a movie – prompting “some to denounce her treatment as second-class.”

In “Painting With Fire,” created the nursery room of the Schindler House, Soto-Diaz imagines the princess burning her pink plastic castle – purchased on Craigslist, of course – in an act of feminist defiance. Wooden corner structures pair video and paintings with scorched plastic, plexiglass and vellum in “a visual conversation with (the building's) brilliant modernist architecture.”

Ultimately, the goal of “How to Read El Pato Pascual,” Chagoya said, is to “open the door for dialogue” about the troubled relationship between the United States and Latin America, “hopefully through some sense of humor.” After all, he added, “We will never solve this problem with art alone.”

Top Image: "The Governor's Nightmare" by Enrique Chagoya | Courtesy of the artist