How the New Deal Continues to Shape L.A. 90 Years On

Note: The opinion expressed here is solely of the author and does not reflect the views of PBS SoCal, KCET or Link TV.

If FDR were alive today and you tried to thank him for all the "infrastructure" his administration built, he would have no idea what you were talking about. He and Harry Hopkins, the chief architect of his Works Progress Administration, thought they were creating "public works."

In fact, if the military hadn't picked up the word "infra-structure" from the French while rebuilding postwar Europe and brought it home, Congress might not be having this whole summerlong tug of war about what the term does or doesn't cover. Who can blame people for thinking that infrastructure has to involve construction? "Public works" is more like it: meaningful work by and for the public. As senators start to dig into Biden's $3.5 trillion package of what Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg has called "social infrastructure," it's a good time to take a look back at what the WPA achieved 85 years ago in Southern California.

Call it what you like, but every time you drive across Los Angeles, or fly in or out of it, or even flush a toilet in it, you can thank FDR, Hopkins and the WPA. If you or your family have ever frequented a park here, attended public school here, or if your grandparents survived the Depression here, you owe the WPA big-time.

Residents of practically every other city and town in America can say the same. Invisibly to this day, New Deal handiwork surrounds Americans everywhere we go — Angelenos most definitely included. Luckily, there's now a crowdsourced website, The Living New Deal, that's mapping more and more WPA projects around the country all the time. That's a challenge, considering that (per PBS) "the WPA built or improved 651,000 miles of roads, 19,700 miles of water mains and 500 water treatment plants. Workers built 24,000 miles of sidewalks; 12,800 playgrounds; 24,000 miles of storm and sewer lines; 1200 airport buildings; 226 hospitals; more than 5,900 schools, and more than two million privies."

Once you know where to look, public works built in L.A. by the WPA become almost hard to avoid. Skeptical? Then meet me at the corner of First and Mednik in East Los Angeles. It's as good a spot as any to buckle up for an exploration of how the Works Progress Administration is still working for L.A..

East Los Angeles: 85 Años de Soledad

I've spent hours visiting the East Los Angeles Civic Center Library and its surrounding 29 acres of green space. I also know 31-acre Belvedere Park on Avenida Cesar Chavez, half a mile to the north. But only lately have I learned that, originally, this was all one park.

Alas, around the time I was born, the Pomona Freeway chopped the green space formerly known as Soledad Park in half. Soledad wasn't the only Eastside park later bisected by a freeway, but at least Hollenbeck Park in Boyle Heights got to keep its name.

Separately or together, Soledad Park has welcomed generations of Angelenos since the 1930s. The L.A Conservancy calls it the "recreational heart of East Los Angeles for over seventy years." In addition to the county library and other municipal buildings, the spacious grounds of the East L.A. Civic Center offer a large lake that hosts everything from Shakespeare performances to a trout-fishing derby. Across the freeway, Belvedere has a baseball diamond built by the Dodgers Foundation, a soccer field, a skate park and an enormous swimming pool, complete with its original stylish tile-roofed clubhouse.

What neither half of the original Soledad Park has, at least that I could find, is any indication of who created all this. Most WPA sites supply little or no signage commemorating any of the legions of workers who left us this legacy, nor the program that employed them to create it. Occasionally, you find the odd brass or bronze plaque — or a blank niche where a plaque used to go. Sometimes, at most, you might spot "1939" or another Depression-era year chiseled enigmatically on the approach to a bridge.

Was the WPA's reluctance to call attention to their own handiwork mere modesty? Or reluctance to become too obvious a target for the Project's enemies? Whatever the reason, this reticence has left generations of grateful beneficiaries in the dark about whom to thank.

The WPA's lack of commemoration will become a pattern as you and I motor west…

Downtown: The Harry Hopkins Bridge?

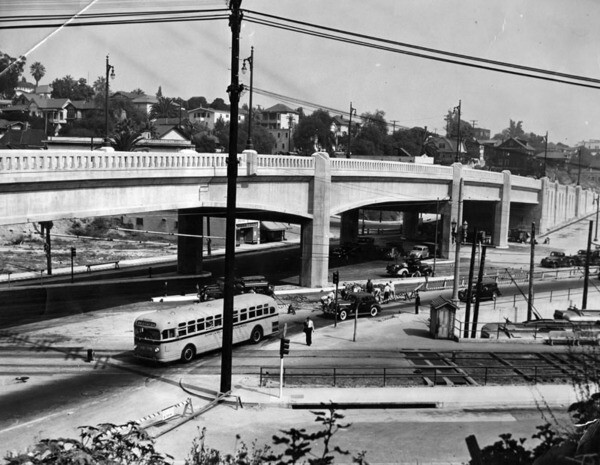

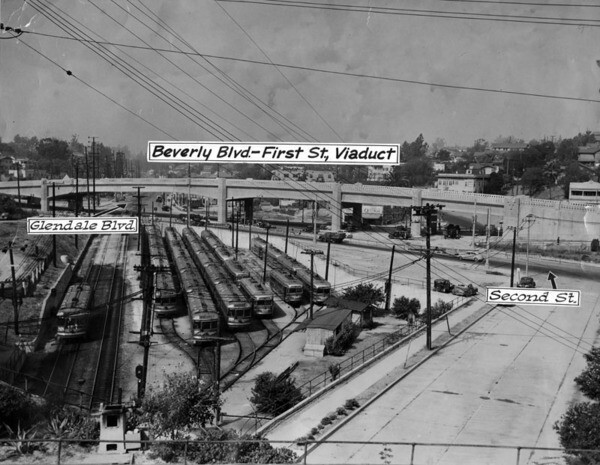

The First and Glendale Viaduct downtown turns First Street into Beverly Boulevard, gracefully bestriding Glendale Boulevard below. A real workhorse of downtown surface transportation, it originally spanned some very busy Red Car tracks. We're heading west over it, but lucky eastbound drivers get a fairytale view of the downtown skyline, a gorgeous three-dimensional WPA mural brought to life.

The bridge stands as just one monument among thousands to all that Harry Hopkins and the WPA accomplished. Come to think of it, renaming the bridge after him would only be justice. It would also be, incredibly, the only monument dedicated to him in the entire country.

While we're at it, we could name the nearby WPA-built Figueroa Street Viaduct of the Pasadena Freeway after Frances Perkins, FDR's female labor secretary, who midwifed the creation of both unemployment insurance and social security. The sturdy Fig Viaduct carries traffic over the L.A. River and several train tracks — and today the Golden State Freeway. Surely by now I don't have to tell you whose labor helped build the sinuous Pasadena Freeway itself.

OK, hop back in. We're headed for Griffith Park, the Central Park of Los Angeles — if only Central Park were five times bigger and had a mountain range running through it....

Griffith Park: Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler, Newton and … Iron Mike?

On Oct. 1, 1935, FDR visited Los Angeles and saw for himself how the New Deal had begun transforming the city. In Griffith Park, he attended the unveiling of a statue honoring the Civilian Conservation Corps. You can still see the figure of "Iron Mike," aka the "Spirit of the CCC," standing sentry in the middle of Travel Town with his trusty shovel.

Everywhere around him, Roosevelt would've seen a park coming to life. The Conservation Corps paved roads, blazed trails, created tennis courts and a municipal golf course, even installed a sadly decommissioned hillside sprinkler system in the event of brushfire. Just up the hill, on the greensward in front of the Griffith Observatory, WPA artists sculpted the Astronomers Monument, anachronistically exalting science as indispensable to any viable republic.

All this work has paid off. Estimates put Griffith Park annual visitors at about 12 million a year, eclipsing numbers for even national parks like Zion or Yosemite.

Roosevelt's brief crib sheet for his address to the young men of the CCC survives in the archives of the FDR Presidential Library. His "INFORMAL EXTEMPORANEOUS REMARKS ... AT THE UNVEILING OF THE STATUE ERECTED BY CCC TRANSIENT CAMP" last all of three sentences:

"I am glad to be here and take part in the dedication of this great statue. It is good to see you all. You are doing a splendid piece of work. (Applause)"

Rhetorically, it falls somewhere short of the great "Second Bill of Rights" speech to Congress in 1944, the one where FDR declared every American's right to a job, a home, healthcare and a good education. But imagine what it must've sounded like to hundreds of poor kids bivouacked in Griffith Park — gainfully employed for the first time, out in the fresh air all day, camping at night with new friends under then-visible stars, hearing their president give them a pat on the back.

The legacy of these workers isn't just the trails we hike or the putts we sink. It's the example they bequeath to us of a government that once valued its citizens enough to put them to work for the good of their neighbors.

Feeling the heat on our westbound drive? Let's pull in at an example not just of the grace of the WPA's Los Angeles work but of its ingenuity…

Beverly Hills: It's a Wonderful Building

The hangar-shaped Beverly Hills High School Swim Gym built in 1939 looks like an ordinary indoor basketball court — until basketball season ends. That's when the hardwood divides at center court and recedes beneath the bleachers, revealing an aquamarine, tournament-sized swimming pool. In "It's a Wonderful Life," Jimmy Stewart and Donna Reed dance right off the edge and into the drink.

Under this parquet have swum such surprising Beverly alumni as the beloved LA Times restaurant critic Jonathan Gold, the columnist and screenwriter Nora Ephron, Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas, filmmakers Rob Reiner and Albert Brooks and the fine novelist Mona Simpson, who set her debut novel "Anywhere But Here" at Beverly. (On the minus side, there's lobbyist and convicted felon Jack Abramoff.)

Some of my old Beverly classmates now employ fleets of accountants to keep their taxes to a minimum. They may think that government outlays help only other neighborhoods, never their own. Don't they realize how they themselves once benefited from government largesse — and how their children still benefit, every time they suit up for P.E.?

Santa Monica: The WPA's Greatest Gift

The WPA proved especially kind to Santa Monica, partly because of the city's need for extensive rebuilding after the devastation caused by 1933's Long Beach Earthquake. City Hall, the post office and half a dozen schools in the Bay City were all either built or rebuilt by federal labor.

Think of the thousands of students still learning today in these classrooms. Now think of the hundreds of thousands of Santa Monicans educated on these campuses since the 1930s.

While you're at it, think of the countless WPA projects we've passed on our way from East L.A. today to the Pacific — the parks, the roads, the bridges, the schools. All these durable public works were designed and built at decent wages with regard not just for usefulness but for beauty.

The disparate projects we've visited comprise just an arbitrary fraction of all that the New Deal did for L.A. We could just as easily have visited any of the following, all built, rebuilt or improved by the WPA:

- Angeles Crest Highway (and many other highways)

- The Ballona Creek Channel (and, likewise, others)

- Los Angeles International Airport (and others)

- Elysian Park (and others)

- Hollywood High School (and others)

- Venice Post Office (and others)

According to the Living New Deal website, the WPA worked on more than 140 projects in L.A. — and those are just the ones catalogued in more comfortable neighborhoods, where volunteers have had time to do the research. Treasures likely await amateur WPA historians in more working-class neighborhoods.

My favorite WPA project isn't a road or a bridge or even a school. It's not a library, but you're getting warmer. The Santa Monica Main Library has a gorgeous Stanton Macdonald-Wright mural that spent 40 years in storage before somebody remembered and restored it — but even that's not my favorite.

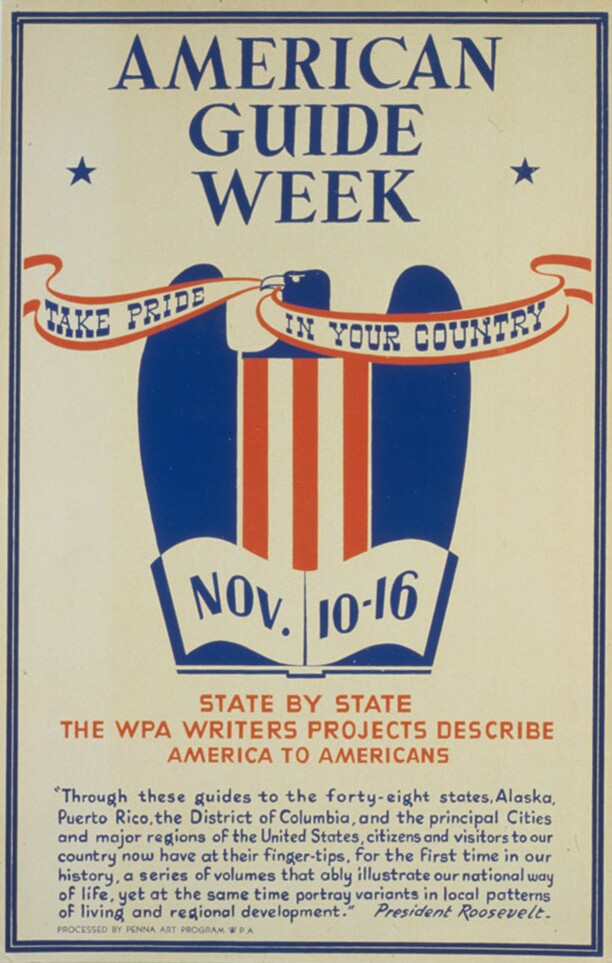

No, only if you visit the Santa Monica Library — or any good public library in the country — can you find jewels from the best WPA project of them all: the Federal Writers' Project, which created American Guides to all 48 states.

In addition the states, forty cities around the country had guides, too, many available in inexpensive reprints like this one from University of California Press:

If you're curious, the Federal Writers' Project is currently, finally, up for renewal in Congress. Congressman Ted Lieu' 21st-Century Federal Writers' Project Act (H.R. 3054) would allocate $60 million to create 900 to 1,000 jobs for writers, editors, photographers, web developers, librarians, teachers and other gifted storytellers.

Their brief would be essentially threefold: 1) to document America's recovery from the pandemic, 2) to pick up where the original WPA guides left off, chronicling the story of the country and its people and ultimately, 3) to reintroduce America to itself.

A new Federal Writers' Project might yet create the one public-works project that all the other WPA projects could fit snugly inside of: a brand-new shelf of these thoroughly researched, enjoyably written, handsomely produced American Guides. (If you agree, please contact the labor point person in the office of your member of Congress and [concisely!] invite them to co-sponsor HR 3054.)

But does a shelf of books qualify as public works, let alone infrastructure? Does it really deserve a place in an omnibus package alongside parks and bridges and schools?

As far as I'm concerned, public works are anything that will still be useful in 90 years. By that definition, the WPA and all its projects not only meet that criterion — they're still paying Angelenos back to this day.

Now, multiply the WPA's achievements in L.A. by all the cities and towns in the country. Could America possibly do anything as important today?

Could we forgivably do anything less?