How a 20-Second Film of Black Performers Kissing in 1898 Was Rediscovered. And Why It Matters.

For Dino Everett, a film archivist at USC's HMH Moving Image Archive, it was commonplace to receive dozens of boxes and bags filled with unidentified film reels dug up from dusty attics and the deepest corners of private homes. But most of what comes through are copies of news reels and silent versions of comedy films made in mass and sold for cheap by film company Castle Films in the 40s and 50s — or what Everett calls the film equivalent to "junk mail."

So, when, one day, he received a nitrate reel that revealed a Black couple kissing and embracing joyously, Everett knew he was holding on to something unlike anything that had been sent before.

"I pulled through the whole film and there was never a joke attached to it," Everett said. "So, I was like, 'Okay this, I think, is important.' Because here are these African Americans kissing. They’re not part of a joke. This doesn’t ever happen."

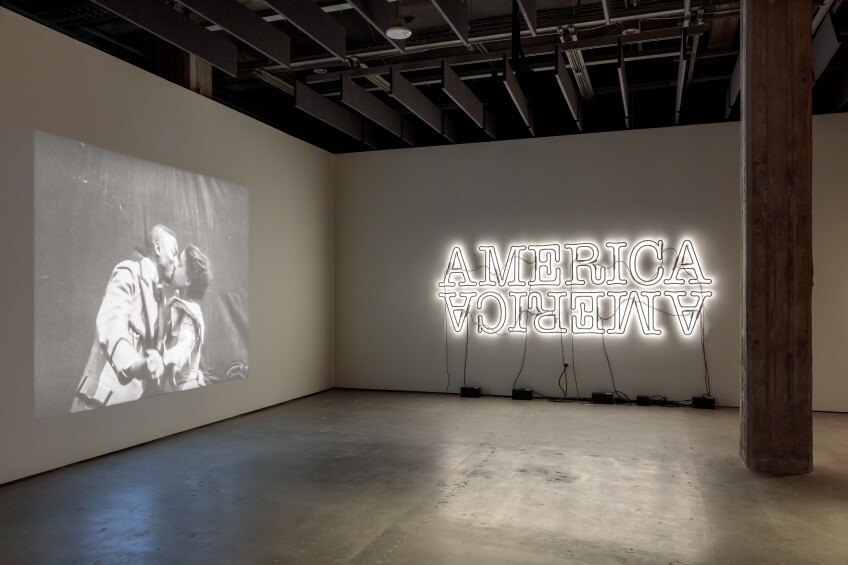

That roll of film would later be identified as the 1898 short film by William Sellig called "Something Good – Negro Kiss" — one of the earliest on-screen depictions of a kiss between Black actors. The film, with a runtime of about 20 seconds, is featured prominently in the recently opened "Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898-1971" exhibition at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures.

In the dizzying turn-of-the-century film, vaudeville performers Saint Suttle and Gertie Brown are dressed in dignified Victorian-era costuming and share several kisses, pulling back and swinging their arms side-to-side in between each one. The moment is tender and sincere — a stark contrast to the popular minstrelsy shows of the time that depicted racist caricatures of African Americans, framing Black performances and performers as comedy.

"It provides you with a counterbalance to these stereotypical pejorative images, and expanding our understanding around film and around Black representation within film. That there was more than one way that people were presenting themselves and being presented, which completely challenges our preconceived notions around African American presence in moving imagery," said Rhea L. Combs, a Black cinema scholar who co-curated "Regeneration" alongside Doris Berger, Vice President of Curatorial Affairs at the Academy Museum.

Much of what makes "Something Good – Negro Kiss" surprising for present-day audiences has a lot to do with Suttle and Brown's genuine performance paired with the contextual knowledge of when the film was made and distributed. But identifying these details — like when the film was made, its filmmaker and the performers — wasn't a simple task. It was a collaborative investigation of nearly two years.

Solving a Film Mystery: Identifying "Something Good – Negro Kiss"

Upon unrolling the original nitrate reel for "Something Good – Negro Kiss," Everett reached out to Allyson Nadia Field, an associate professor of film and media studies at the University of Chicago who specializes in the intersection of race and cinema. The duo's process was a combination of analyzing physical evidence hidden in the roll of film and digging through archival film catalogs, production records and newspapers.

Circular perforation marks found along the edge of the film strip were one of the first clues that narrowed down Field and Everett's search. The faint markings were a distinct feature of a camera manufactured and used by French filmmakers and cinema pioneers, the Lumière brothers. But archival research found that "Something Good – Negro Kiss" did not match any of the Lumière brothers' catalog of film descriptions. The Lumière trail dead end led Field and Everett to William Sellig, a Chicago-based American filmmaker who reverse engineered the Lumière brothers' cinématographe to create his own camera and produce short films in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

A deep dive into various Sears motion picture catalogs printed at the turn of the century confirmed Sellig as the filmmaker. Among dozens of cataloged films, was the title "Something Good – Negro Kiss," paired with a thumbnail illustration of one of the film's frames and Sellig's name listed as the filmmaker.

But the identity of the film's performers was still a mystery. According to Field, unless you were a popular performer of the era, visual records for stage actors didn't exist and crediting performers wasn't commonplace in early cinema. A database at MoMA would offer up a clue that would lead Field and Everett to the final piece of the puzzle. At the time, MoMA was working with a 1900 short film, "Sambo and Jemima, Comedians," that also featured a kiss between Black performers, one of whom was Saint Suttle. The identification of Suttle then led to a photo of The Rag-Time Four, a vaudeville quartet he performed in along with Gertie Brown.

Upon its official identification, "Something Good – Negro Kiss" made its rounds through social media, earning praises and awe-struck reactions from thousands of Twitter and Instagram users, most notably actress Viola Davis and filmmaker Barry Jenkins.

"If there is something like restorative justice for underrecognized figures of film history, I hope this might be a small part of it. At the very least, this is a process that has allowed Suttle and Brown's audience to grow to the millions, 120 years after they first kissed before the motion-picture camera," Field wrote in her essay, "Archival Rediscovery and the Production of History: Solving the Mystery of 'Something Good – Negro Kiss.'"

"It's bittersweet to have [Suttle and Brown] in the Academy […] in the sense that they are now welcomed into a space and celebrated by this institution that they never would have had access to in their careers," she added in an interview with KCET Artbound.

Finding the 'Lost' Pieces of Black Cinema

With the excitement surrounding the recent rediscovery of "Something Good – Negro Kiss," it begs the question — what other lost pieces of Black cinema history could be out there, waiting to be found? For Combs, she and Berger hope that "Regeneration" sparks more curiosity and interest around Black cinema and inspire viewers to keep digging for lost pieces that are likely hiding in plain sight.

Following the rediscovery of "Something Good – Negro Kiss," an alternative, extended cut of the film surfaced in Norway — a version that had been sitting, unidentified, in the National Library of Norway for decades. The extended cut is shot at a wider angle and reveals more playful banter and performance between Suttle and Brown, finishing the act with a grand kiss and a twirl.

"It was through the finding of the one in California that Norway was able to say, 'Hey, we've always wondered about this.' And it allowed them to recognize the work that they have, " Combs said. "And so that's just an example of how I think the potential for new discoveries is ripe."

As a film archivist, Everett remains an optimist about "lost" cinema.

"I like to think of these things as simply lost," Everett said. "It's not like they're erased from the earth. They're just lost. We haven't quite found them yet."

"I do believe that there's lots and lots of material in private hands," he added. "And people might not even know it's film. It's just Pop-Pop's stuff, you know? And nobody's really taken the time to go through it."

Such was the case for "Black Chariot," a 1971 independent film by Robert Goodwin that had been considered lost and gone. Produced and released at the advent of the Blaxploitation era, a subgenre of low-budget independent films made for, and oftentimes by, Black filmmakers, "Black Chariot" was "lore," never again seen by anyone outside the small group of people who watched it upon its release.

It was a family member who reached out to Combs as she was in the process of co-curating "Regeneration" and claimed to know the whereabouts of "Black Chariot." Unbeknownst to most of the world, the film had been sitting in the living room floor of an unoccupied apartment in Mid City, Los Angeles, "almost around the corner from the museum." The film roll has since been confirmed as "Black Chariot," cut, preserved and restored to be screened for the first time in over 50 years at the Academy Museum on Sept. 29 alongside the 1971 Black independent film "Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song."

"We really do hope that these kinds of finds will spark others to continue to dig," Combs said.

"Many museums only put a fraction of their collection on view, meaning that there are legions of things behind in their archive space. And oftentimes, those things don't see the light of day unless there's a curator who, by chance, is looking for something or an archivist that has a spare moment to dig through. And oftentimes, these things are found by happenstance."