Herman Sillas' Art and Activism

In the City of Huntington Park, Herman Sillas is a legend. A noted Chicano activist, the lawyer of Sal Castro -- infamous teacher arrested during the 1968 Los Angeles Walkouts -- and revered artist, the presence of Sillas at the Huntington Park Public Library creates a stir and fills the building. Regularly, Martin Delgado, head librarian of the Huntington Park Public Library invites Sillas to discuss his trajectory from the son of working-class Mexican American parents to noted civil rights lawyer and award-winning painter. In a city of largely working-class Latino immigrants, Sillas finds it necessary to remind both the young and the complacent that the Mexican American and Latino communities across Los Angeles need to continue to strive towards equity and excellence. When sitting amongst a crowd of fascinated teenagers hanging on the every word of Sillas as he discusses when Los Angeles was segregated and when Spanish was banned from Los Unified School District classrooms, they seem spellbound as though listening to fairy stories or a far away land. But the trajectory of Mexican Los Angeles from a marginalized minority to an upwardly mobile citizenry is a real and recent history which Herman Sillas has both contributed to and documented along the way through both legal briefs and painted canvas.

Herman Sillas remembers the events which shifted his life. Though just a private practice attorney in East Los Angeles, his position in the city radically changed in August of 1965. For seven days, hundreds filled the streets and looted and burned the commercial section of Watts as protest against police brutality suffered by African Americans in the South Central area of the city.

As the city burned, Sillas brought every member of his family from their homes in Inglewood and South Los Angeles to his in the Eagle Rock. Such acts of dissension had become common across the nation since World War II and often they were centered within ethnic minority communities. Sillas no longer resided in South Los Angeles, but worked in downtown Los Angeles as one of the few Mexican American lawyers within the city. Daily he crossed the divide between middle class white Los Angeles into the world of immigrants and Spanish language speakers. He still often marvels at how wide the gap between ethnic communities of the city and the white majority stood during this era; he even recalls during the riots a neighbor commenting, "You gotta full house this evening. I heard on the news about some burnings or stuff going on?"

Though the Watts Riots were predominately an African American act of protest, city leaders became concerned with rising discontentment within other ethnic minority communities, especially, the Mexican American community; city leaders literally worried over black and Mexican American communities becoming the "tip of the spear" for Communist interests imbedded across the nation and decided to head off further discontent by consulting professional leaders from minority communities in the form of the Los Angeles County Human Relations Commission. As one of the few Mexican American professionals in 1960s Los Angeles and a graduate of UCLA's School of Law, Sillas was invited to participate.

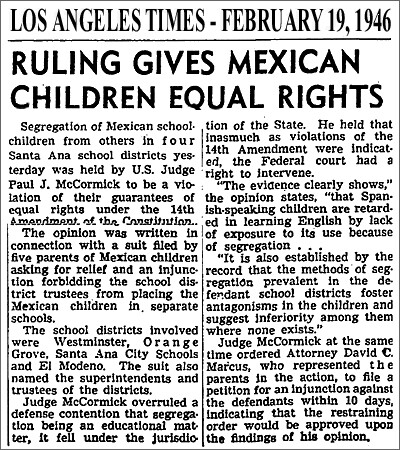

By the time Los Angeles formed the Human Relations Commission, the wheels of change had already begun to move. In 1946 the California Supreme Court desegregated schools across the state through their Mendez v. Westminster ruling, in 1961, interracial groups of civil rights activists from around the nation risked life, limb and reputation to integrate interstate bus travel through the Freedom Rides and waves of other public protests against racial and cultural hierarchies emerged in a number of states across the nation. But in spite of the growing vocalization of minorities against racism and discrimination and the slow increase of black, Asian and Latino students in major universities, no major law firm in Los Angeles hired lawyers of Mexican descent. Schools across the district banned Latino students from speaking Spanish on campus and the neighborhoods remained segregated under the illegal but common practice of redlining.

In hopes of assuaging the frustration of Chicanos across the city, the Human Relations Commission gathered to deal specifically with poor housing, inequitable education and widespread unemployment. Interestingly, the goals of this Committee became far more involved than mere economic improvement. Both Mexican American activists, as well as academics like Marcos de Leon pushed for deeper change within the Chicano community like addressing the community's widespread loss of Spanish language skills and the absence of a strong Mexican identity. To Sillas' amazement, this included him. Never had he deeply considered the childhood experiences which taught him that Spanish words "did not count" or feelings that his Mexican identity was inferior.

As he continued to meet with members of the Human Relations Commission he began to remember experiences which subtly taught him that Spanish and other associations with Mexican culture were considered inferior by the majority population. He recounted that while in the first grade, his teacher challenged each student to think of a word that begins with the letter "C." One by one his classmates rose and offered their word -- "cat," "cookie," "can." To Sillas' dismay, many of the words he considered were shared as his turn neared. Finally, the question came around to him, "Give an example of a word that starts with the letter, 'C.'" After some thought the young Herman Sillas became ecstatic; he'd thought of a word to share with the class -- "Chanclas." He confidently rose and stated his word to his teacher and classmates. "How do you spell such a word, Herman?," his teacher asked. He did not know. "My mother wears chanclas on her feet," he announced. To end the discussion his teacher stated, "There is no such word, Herman, you need to pick another word." He stood confused, he visualized his mother's chanclas in the closet, she wore them daily around the house, once she even swatted his bottom with one of her chanclas. They definitely existed. He recalled that moment as marking the first time that he realized that Spanish words held no value in a predominately white school.

From that moment on, Sillas distanced himself from both in hopes of being more successful. By the time he completed his law education, he had for years consciously allowed his Spanish to lapse but no white firm would hire him. He soon realized that the language of his parents stood as essential for him to successfully gain employment in his field and advocate on behalf of his Mexican American neighbors in cases of discrimination, low wages and an overall lack of opportunities. Like a "gringo" he was forced to study Spanish in the evenings to maintain his practice and feed his family.

After many Human Relations Commission meetings and dinners discussing the crisis of language and identity within the Mexican American community across the nation, he ultimately felt compelled to purge years of bottled up frustration and paint his first work entitled, "The Mexican American," in late 1965.

By splitting the canvas in half with one half depicting the Mexican-ness of his community and the other the American-ness of Chicanos, Sillas explored the ongoing tug-of-war of culture and identity found within many children and grandchildren of Mexican immigrants. Direct conflicts of values permeated his painting as they did his life. With one side defined by masculinity, Catholicism and revolution and the other by time, liberty, corporatism and feminism, Sillas articulated the two-ness which lay at the core of the Mexican American community; so many of his community members struggled to balance the expectations of the dominant white society with those of their Mexican traditions, families and Catholic faith. The work struck a cord with leaders within the Chicano Movement and was featured in El Malcriado the newspaper of the National Farm Workers Association -- the organization founded by Cesar Chavez and the voice of farmworkers across California. Sillas claims that after painting "The Mexican American" he no longer struggled with an identity crisis and fully embraced his Mexican roots and culture.

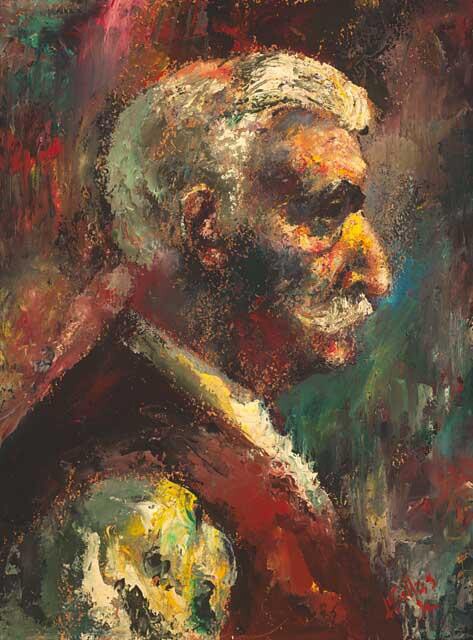

A year after joining the Human Relations Commission, Sillas and a diverse mix of Los Angeles lawyers decided to found their own law firm. As a newly defined Chicano activist and member of the California art community, Sillas convinced his colleagues to set aside $900 and an entire wall in their new space to depicted "The History of the Law." Ultimately, the firm hired the later renowned Armando Campero--a former student of Diego Rivera and an aspiring muralist. Campero recently arrived in Los Angeles and had inquired around the city about opportunities to paint Mexican-styled murals. According the Sillas, city officials told Campero, "No." and even Sillas recalled stating, "City walls are for advertising not for art." As a last resort, Campero sought support from the Mexican American Lawyers Club and the perfect storm of the firm's small art budget and large wall allowed Campero to launch his art career in California; he went on to paint murals around East Los Angeles. (Unfortunately, Campero's mural was destroyed with Sillas' law firm was firebombed.) By working in close proximity with Campero daily, Sillas received encouragement to continue painting especially after his success in publishing "The Mexican American" in El Malcriado. Using tight compositions of the people and culture he re-embraced and worked for daily, Sillas painted those historically overlooked--working class Latinos, migrant workers, and those left behind in Mexico.

As Sillas and his colleagues settled into their law offices in East Los Angeles, the Chicano Movement gathered steam with the National Farm Workers Association's call for a labor strike against the largest California grape growers in the Central Valley which ultimately lasted five years. Across the nation Mexican Americans rallied for positive change in their local communities. The culmination for educators and students in Los Angeles were the East LA Blowouts in 1968. In 1966 Sillas assisted in organizing the Association of Mexican American Educators in which local educators officially questioned the quality of education provided by Los Angeles Unified School District particularly the overt stripping of Mexican culture from LAUSD students, failure to prepare Mexican American students to compete on a university level (especially as a number of them were channeled either into industrial courses or courses set aside for "Educationally Mentally Retarded" students due to their first language being Spanish), and the banning of the use of Spanish on campus. Of the teachers gathered under the AMAE, Sal Castro stood out from his colleagues as he challenged students to take responsibility for agitating for the improvement of their own education and despite threats of having his teaching license revoked, Castro walked out with thousands of students.

Sillas recalled Castro justifying his efforts by saying, "What does it matter to have a license if you can't teach kids what they need to be taught." Following the Walkout, hundreds of students were jailed and Sal Castro was charged with the felony -- conspiracy to commit a misdemeanor and his case was brought before a grand jury. As a visible supporter of the Chicano Movement within the city, Castro hired Sillas as his lawyer and ultimately the trial was thrown out of court because of discrimination within Los Angeles' jury selection process. In the history of grand jury cases, less than three Mexican Americans had ever been summoned to serve on the jury. The judge agreed that Sal Castro would not have received a fair trial. The Walkouts proved to be a pivotal point in the history of Los Angeles as the school board found themselves forced to alter discriminatory practices citywide. Mexican American culture and the Spanish language were fully acknowledged in the city's schools.

Years later in 2008, Herman Sillas was commissioned to paint a mural depicting the experiences of Mexican Americans for the 40th anniversary of MALDEF--Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund. In the submitted mural, "MALDEF and Latinos Shaping America," Sillas painted the spectrum of the Mexican American experience across the nation -- from the legions of well-heeled professionals climbing the corporate ladders of national and multi-national companies to regular family gatherings in the parks to the ongoing awareness of road signs warning of Mexican and Latin American souls darting across busy highways, he painted it as all a part of the patchwork quilt which is the Mexican American experience and Sillas spent his career working to give that experience dignity and stature in a historically unwelcoming society.

In textbooks Herman Sillas is canonized as the lawyer who defended Sal Castro and the students of the East Los Angeles Walkouts but in the Chicano art world, Sillas has lent his talents as a painter to articulate the inner struggles had by Mexican Americans at the height of the Chicano Movement -- the near loss of culture, the lapse in Spanish language skills and the growing cultural amnesia had by so many Mexican Americans before the height of the Chicano Movement. Sillas' paintings are visualizations of split identities and the seeking of cultural awareness in 1960s Chicano Los Angeles but they are also pictorial memoirs of a witness to social change.

Dig this story? Sign up for our newsletter to get unique arts & culture stories and videos from across Southern California in your inbox. Also, follow Artbound on Facebook and Twitter.