From Gangs to Art: The Salvation of Fabian Debora

In partnership with Boom Magazine Boom: A Journal of California is a new, cross-disciplinary publication that explores the history, culture, arts, politics, and society of California.

This article was originally published in Boom: A Journal of California.

The image is stark. An East L.A. gang member, neck swathed in tattoos, stares out over a burning Los Angeles skyline. Clouds brood above. Behind the gang member, four children stand at a cliff edge as if about to plunge off. The scene is apocalyptic, intimidating, especially when seen in person. The six-by-four-foot canvas, hanging on a wall in a downtown Los Angeles café, looms like some unwelcome dispatch from the city's dark side.

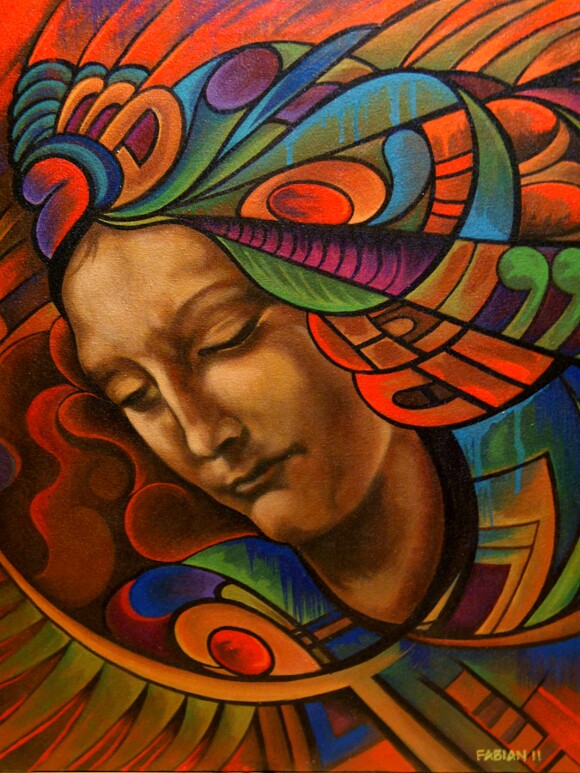

The scene is also familiar, at least to anyone versed in recent trends in Chicano art. The acrylic painting, titled "Pay Me No Mind," is by a former East L.A. gang member named Fabian Debora. It looks remarkably like the work of another, more famous Chicano artist named Vincent Valdez, whose 2009 painting "BurnBabyBurn" depicts L.A.'s fabled grid of nighttime streetlights twinkling, while in the distance, a raging wildfire consumes surrounding hillsides. The similarity is no accident. Debora, whose purchase on the L.A. art scene is more tenuous than Valdez's, interned for Valdez two years ago and describes "Pay Me No Mind" as an effort to channel his mentor's signature, hyper-real visual style.

And yet, for all their surface likeness, the two paintings, and the artists who painted them, could not be more different. Their differences tell a story. Vincent Valdez is a rising art star, educated at the Rhode Island School of Design, exhibiting his work in museums ranging from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. He paints like many latter-day Chicano artists, employing visual irony to address wider themes only tangentially related to traditional barrio concerns.

Fabian Debora, born in America to Mexican parents, grew up the son of a heroin addict and joined one of East L.A.'s oldest and most violent street gangs as a teenager. He wrestled for years with drug addiction, and at age thirty tried to commit suicide by running across the southbound lanes of the Golden State Freeway (Interstate 5). It was only after what he describes as an encounter with God during that suicide attempt that he entered rehab and began seriously to pursue an artistic career. Fabian paints like a man eminently grateful for his hard-won state of grace. "Pay Me No Mind," he informed me, was intended as an inspirational image, an effort to illustrate that pivotal moment when a gang member, or anyone gone astray, finally decides to make a change. The light shining on the gang member's face is meant to signify divine illumination. The gang member, turning away from the burning city below, decides at the same moment to become a responsible father, shielding his children from the flames of his former life. It is a far different vision from that of Valdez, who in an interview described "BurnBabyBurn" as a visual representation of the social "turbulence" generated by Los Angeles, that symbol of American racial tension and economic inequality. Fabian's aims are simpler. "I find the divine in the image of a gang member," he told me. "Art is the closest thing you can get to the essence of God."

Most contemporary artists dedicated, like Vincent Valdez, to stylistic innovation and cultural critique, do not as a rule incorporate such bald religious sentiments into their work. Fabian Debora is not a typical contemporary artist. His biography is not standard MFA fare. More importantly, he has maintained roots in a part of America uniquely suited to fostering his peculiar artistic mix of visual sophistication, street savvy, and spiritual engagement. Fabian grew up, lives, and works in the heart of immigrant L.A. His neighborhood, Boyle Heights, is known for its rich history of migration, encompassing waves of Jews, Russian Orthodox, African Americans, Japanese, and Mexicans. It is also marked by another defining characteristic of immigrant communities: its religiosity. In line with a recent Pew study showing that immigrants, especially those from Mexico and Latin America, are more likely to be Catholic and to believe in God than native-born Americans, Boyle Heights is anchored by Fabian's childhood Catholic parish, Dolores Mission. The church is L.A.'s poorest, and at various times in its 90-year history, it has provided sanctuary for undocumented migrants, staged neighborhood Christmas festivals at which Joseph and Mary's search for lodging in Bethlehem is reenacted as a Mexican border crossing, organized neighborhood mothers to combat gang violence, and run an elementary and junior high school attended mostly by the children of immigrants. The neighborhood is a place where faith and immigrant life are deeply intertwined.

The same goes for the rest of L.A. Thirty-four percent of Southern Californians are foreign-born, according to the United States Census, which is America's highest big-city concentration of immigrants. Like New York a century ago, Los Angeles in recent decades has spawned an immense religious infrastructure ministering to newly arrived migrants struggling to find their place in a nation often hostile to their presence. The Islamic Society of Orange County in the city of Garden Grove, one of America's largest mosques, offers worshipers a complete kit of civic services, including a mortuary, a preschool, an elementary and junior high school, and meeting rooms for weddings and other community activities. In Hacienda Heights, an L.A. suburb a few freeway exits away from Fabian's neighborhood, the 15-acre Hsi Lai Taiwanese Buddhist Temple, the largest in the western hemisphere, organizes summer camps for local youth, teaches Cantonese, produces radio and television broadcasts, raises money for disabled children, operates a printing press, and runs an art gallery.

There are more Catholics in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles -- almost 4.5 million -- than in any other American archdiocese, and Dolores Mission in Boyle Heights was omnipresent in Fabian's upbringing. As an artistically talented student at the parish school, he was encouraged to draw the Virgin of Guadalupe for religious festivals. When he was expelled from Dolores Mission in eighth grade (he threw a desk at a teacher who ripped up one of his drawings), he was sent to see the parish priest, Father Gregory Boyle (a Jesuit who went on to found Homeboy Industries, a celebrated gang intervention program now headquartered near downtown Los Angeles). Boyle became a mentor. He sent Fabian home that day with a pointed request: "I want you to draw something for me." A few years later, after Fabian had drifted into gang life and begun bouncing in and out of jail, Boyle convinced Fabian's probation officer to allow his charge to work as an apprentice to Wayne Healy, one of the founding fathers of L.A.'s Chicano mural movement. In Healy's warehouse studio, Fabian met veteran Chicano artists and recent art school graduates. He learned to paint and worked with Healy on a mural outside the chapel of Eastlake Juvenile Hall, where Fabian himself once had been incarcerated.

Although Fabian ended up wrestling with drug abuse for several years before finally cleaning up and embarking on an artistic career, he never forgot Boyle's redemptive Jesuit vision. He even narrated his bottoming-out suicide attempt to me as a kind of born-again experience. He'd found himself running toward the freeway one afternoon, he said, after fleeing from his mother's attic, where she'd caught him smoking methamphetamine. Scrambling up a retaining wall, he heard voices: "You don't deserve to live. Kill yourself!" He stepped out into traffic. "I saw a turquoise Chevy Suburban coming at me. I looked at the grill of the truck. The smile of the bumper was like a demon. I felt the impact of the truck, but it wasn't the truck. It was something greater and higher than myself pushing me to the center divider. I looked up and saw clouds and birds and peace. I realized that God loved me so much he got me to the center divider and showed me who I could be."

Today, Fabian works a day job as a lead substance abuse counselor at Homeboy Industries and paints in a loft overlooking downtown LA. He has worked on seven murals around Los Angeles and exhibited his work at a few university art galleries and on the walls of Homegirl Café, a restaurant adjacent to Homeboy Industries that recently exhibited "Pay Me No Mind" and other canvases in a series Fabian calls "Childhood Memories." Working for Boyle, Fabian spends much of his life within the shelter of that L.A. immigrant religious infrastructure. His job shows in his art. He has painted gang members bowing at the feet of the Virgin Mary; flowers wilting at an impromptu street-side shrine; a gang member mourning the destruction of a recently razed Boyle Heights public housing project; and another gang member hoisting up a small child with the words "Tu Eres Mi Otro Yo" -- You Are My Other Self. "I'm taking something sad and dead and I see the beauty in it," Fabian told me. "Art allows me to do that."

It is no accident, I think, that an artist like Fabian has emerged in Los Angeles. Writing in the Los Angeles Times Magazine several years ago, critic Josh Kun observed that "a rapidly expanding pool of young Southern California artists is actively redefining what it means to make Chicano art in the new millennium." Fabian Debora is one of those young Chicano artists, but he has charted a path different from many of his contemporaries. His work is rooted less in his city's ascendant place in the international contemporary art scene and more in L.A.'s current status as America's immigrant capital. While many young L.A. Chicano artists, educated at top art schools and courted by international galleries and museums, seek artistic horizons beyond the barrios that once spawned the Chicano movement, Fabian remains tied to his community, painting with the same hunger for inspiration that brings so many recent migrants to L.A.'s myriad religious institutions.

His "Pay Me No Mind" is a perfect illustration. Borrowing from Vincent Valdez to create a recognizably apocalyptic scene, the painting then turns that scene on its head by telling the story of a man stepping away from, not falling into, his own private catastrophe. The gang member at the painting's center is modeled on a friend of Fabian's named Richard Cabral, who, like Fabian, left the gang life and got a job at Homeboy Industries, baking bread at the organization's Homeboy Bakery. The children behind Cabral are Fabian's own four children, who range in age from three to eight. The clouds are painted to draw the viewer's eye upward, toward the sun breaking through: new life, the presence of God. The painting says to a community hungry for good news: "I'm taking something sad and dead and I see the beauty in it." To repeat, it is no accident that an artist like Fabian should emerge in Los Angeles. America's immigrant future is playing out in this City of Angels. If Fabian Debora's art is any indication, that future will involve finding the divine not only in the image of the gangbanger, but in the face of a new America itself.

Dig this story? Sign up for our newsletter to get unique arts & culture stories and videos from across Southern California in your inbox. Also, follow Artbound on Facebook and Twitter.