Enigmatic Artist's Garage Holds Out Against South L.A.’s Gentrification

Garages hold an almost mythical status in the creative life of Californians (Apple, Microsoft, Marc Maron), but for Afro-Angelenos, the converted garage is where one's own cultural identity is formed and preserved. They were the original makeshift recording studios for R&B producers, practice spaces for woodshedding jazz musicians, beat laboratories for experimenting DJs, and workspaces for artists—not to mention de facto theatres, galleries and classrooms for a community shut out of existing (white) institutions. "All sought to create sights of a metaphysical home, places of the dream, wellsprings of the creative," writes Kellie Jones in her new book “South of Pico: African-American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s.” "Even when the notion of homeplace, like the real space of housing, was a significant arena of contention."

An essential if not easily categorized transitional figure, [RoHo's] tangled, frustrating and fascinating career represented the L.A. Black Art aesthetic as it transformed from the historical and representative to the more abstract and what Jones calls, "virtual."

The tumultuous 1960s was where this notion of creative self-preservation seemed to reach some sort of critical mass. Frances E. Williams, who taught night school at Dorsey High School, and her husband, ceramicist William Anthony Hill, started L.A.'s first equity theater out of her three-car garage on Fifth Avenue in the upscale West Adams-Sugar Hill district. University librarian Mayme A. Clayton started her massive archive of African-American history in her Culver City garage that would later evolve into the invaluable Clayton Library. Composer/pianist Horace Tapscott rehearsed his guerilla jazz orchestra in his Leimert Park garage on Saturdays for decades; when he passed away in 1999, the garage held archival tapes from his vital but little-recorded "Arkestra" that became Jazz Collection No. 237, the largest body of work by a Los Angeles artist in the UCLA Music Library.

Remembering the past, however, has an added caveat in Southern California, where, as USC architecture historian Margaret Crawford once noted, "once things are eradicated, they're lost." On a quiet residential street between Crenshaw Boulevard and USC, this may be happening in real time. Chephren Rasika, a 42-year-old film and video producer, is organizing the garage-cum-art studio of his late father, the enigmatic and fiercely independent artist known only as "RoHo." An essential if not easily categorized transitional figure, his tangled, frustrating and fascinating career represented the L.A. Black Art aesthetic as it transformed from the historical and representative to the more abstract and what Jones calls, "virtual." The attempt by artists like RoHo to "reach across time," she affirms in “South of Pico,” "brings us towards a model of Afro-futurism."

This is also a history that is still being written, and it's the work that needs to be done before the archivists and historians arrive that concerns Chephren Rasika — it's not just about preserving the art but the garage itself. Built in 1994 after the Northridge earthquake destroyed the original structure, the space is essentially a split-level art installation, and it reflects its creator's roots in the assemblage movement of the 1960s (he was mentored by Noah Purifoy). Trained in architecture and design, RoHo loved angles, specifically isosceles-shaped ones like church steeples or the edges of sun-rays, and so embedded many of them in the structure, which is pregnant with arty detritus. There are sensual mounts of rounded abstract feminine curlicues; three-dimensional pieces built out of chimerical combinations of old rocking chairs and repainted cereal boxes; paintings of John Coltrane and a large upside-down American flag that hung in the Governor's Mansion during Jerry Brown's first term; a spirit box with layers of panes of glass embedded with tiny selfies; large wooden sculptures that look like someone deconstructed a 'schwa' symbol and put it back together in Cubistic fashion. "People would probably call him a hoarder, but every part had a use," says Rasika. "This was his functioning living art piece; he planned this out for years. When there were certain points of the day he wanted light in certain areas." A firm believer in the fusing of art, architecture and spirituality, RoHo used the ancient random-number generator known at the I-Ching. "He'd throw down the I-Ching to figure out the lengths of the angles and how they all fit together."

At the same time, the Big "G"(entrification) has been licking at the margins of the surrounding neighborhood due to the construction of the new Metro Line and attendant plans for the reboot of the Baldwin Hills-Crenshaw Plaza mall. RoHo's studio has been threatened by a recently instituted building code: The point of contention is in the back southeast corner, a spire that sticks up three feet past the legal limit. When the warning letters first started arriving from the city, RoHo corralled some of his many artist friends to write letters of support and things quieted down. But after he passed away two days after New Years' Eve 2016 at age 70, the letters started arriving again to his son. The first contractor Rasika consulted wanted to demolish the structure completely. Not surprisingly, Rasika balked. "This back place is the essence of our family," he affirms.

The "garage" of the former Donald E. Davis is redolent of a maverick and somewhat restless career. Although he came off like an outside artist, he anything but. Born to a middle-class family in 1945, he was a graduate of Santa Monica High School and L.A. Trade Tech. A bit of a prodigy, he was only twenty years old when he became one of the handful of African-Americans working in Universal Studios' art department in the mid-1960s. He lasted a year. "That was not a happy situation for him," recalls filmmaker Barbara McCullough, who met him in 1972. "There was some prevalent racism on the lot, so he essentially left...he didn't really talk about it; he just touched on the experience." He worked as a car washer and dishwasher. He moved north to teach painting at the San Francisco College for Women before opening his own design business, Art and Fashions. Moving back to Los Angeles, he involved himself in the Black Arts Movement in Watts.

In the early 1970s, he went to UCLA to study with Richard Diebenkorn. By the time McCullough met him on north campus, he was already calling himself "RoHo Rasika" (Swahili for "Soul/Spirit" and "Essence of Creation") and had steeped himself in Egyptology and the experimental films of Stan Brakhage and Maya Doren. He was not bereft of ego, and they soon began a relationship. "He was a short person who walked like a tall person," McCullough remembers. They would split soon after their only son was born, but McCullough credits RoHo with introducing her to the avant-garde, specifically film and jazz, that would later inform her work with the "L.A. Rebellion" school of filmmakers.

Even at the UCLA of the early '70s, he was a bit of an outlier. He dabbled in acrylics, sculpture, collage, woodworking and photography. He also kept wandering over to the film department and — to everyone's irritation — started making films. They were allusive, freeform, personal endeavors like "Self-Portrait," "The Party" and "Fire" (which featured the poet Ojenke from the Watts Writers Workshop). "He got a lot of flak from UCLA because he wasn't in the film department," says McCullough. "They didn't know his political point of view. It was rough on him. Some in the film department dubbed him 'Andy RoHo' after Andy Warhol." (Apparently, during a didactic era, this was considered a grave insult.) They were especially irked when, with no prompting or introduction, RoHo and two other non-UCLA artists secured $5000 from KNBC to make a 30-minute documentary.

Which explains the box full of reel-to-reels that his son would stumble upon over forty years later. “The Tip of the Iceberg,” which aired on Channel 4 the day after Independence Day 1973, may have been RoHo's most remarkable accomplishment. Along with a Long Beach art instructor named Phillip Mackelroy and cameraman Roderick "Quaku" Young from the Malcolm X Center, he approached KNBC with a proposal for a documentary on South Central's emerging gang culture.

Surprisingly, KNBC executives approved the project — but added a caveat: They wanted their cub sportscaster Bryant Gumbel to host. "RoHo and Phillip met with him and thought he was too 'boojie'," says McCullough. "So RoHo thought of [actor] William Marshall, who had a connection with the community through his teaching at the Watts Happening Coffeehouse." She recalls with a laugh the time Marshall came over to the house they shared to discuss the project, one of her older children opened the door and immediately recognized the 48-year-old actor from his most famous role: "Mom! Blacula's at the door!"

During this time, RoHo and Young also began a loose affiliation with Studio Z, an art collective that included David Hammons, Senga Nengudi, Maren Hassinger, Ulysses Jenkins and Houston Conwill. Studio Z specialized in art you couldn't buy — namely, improvisational, performance-based masquerade tableaux staged usually in the disabused public spaces of Los Angeles like the off-season Greek Theater, an empty swimming pool in an abandoned Catholic School or underneath the Harbor Freeway. When Hammons and Nengudi began to spend more time in New York, RoHo began staging concerts and poetry readings in Studio Z's cavernous space in Inglewood that was once an old dance studio, booking his practitioners of avant-garde jazz such as saxophonists Julius Hemphill and David Murray, pianist Horace Tapscott, woodwindist John Carter, trumpeter Bobby Bradford and the performance-jazz troupe the Art Ensemble of Chicago. Photographer Tylon Barrea attended the latter: "During Malachi [Favors]'s solo, one-third of the ceiling fell down — and nobody paid any attention."

In the early 1980s, RoHo returned to his métier when he worked for Hub Cities designing modular housing in Compton. Needless to say, the work gave him little outlet for his inspirations — mainly the desert architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright and Paolo Soleri. He soon parted ways with Hub Cities and in 1990, with two former Studio Z members Ronn Davis and Joe Ray, formed the multi-racial, multi-generational Zip Zap collective, which continued Studio Z's aesthetic of art in public spaces. The theme of their 1997 show "Vital Signs," staged at the Santa Monica Mall, was the connectivity of I-10 Freeway to which each artist contributed autobiographical found artifacts. RoHo contributed silver Cadillac hubcaps (in honor of his father, a Cadillac salesman) and branches from his own backyard. "It seems like the 10 draws everyone," he told a local reporter. "Everyone who knows Los Angeles knows the language of the freeway."

By design, it was one of RoHo's few public statements. In his father's mellifluous files, Rasika proffers a list in handwritten script headed "Portfolio & Proposals"; the absolute last entry is telling: "Do P.R."— like a dreaded afterthought. "My father didn't like dealing with the fakeness of trying to promote himself," he explains. "It was his truth, but it was bad for his business...His friends would say, 'Roho your not gonna be wealthy, but your son's gonna be.'"

During his later years, as his eyes and heart failed, RoHo turned increasingly inward, and the garage communicates this. You enter it and enter into some lost link between Frank Gehry and Simon Rodia, but you also enter a disquieting conversation with an increasingly insular artistic life that knew how to produce but did not know (or cared) how to market or distribute — a proud, sensitive soul howling in the wilderness. It now falls to the son to arrange and make sense of a legacy he only half-knew, and to pass it on to his two children. Some of the pieces sit half-finished, some unpainted, some are degraded or destroyed by four decades of Southern California weather. You look at the bicycle dangling from the rafters or the ugly smears of patch-up plaster, and you think of loss and stasis.

But then, true to its designer's design, you can see different parts of the studio catch the moving light of the day. A canvas tarp adorned with abstract glyphs hangs just under a patch of sun as it slowly moves into its embrace and the ceiling and tarp being to glow. You realize this was not a man behind his time. You open old sketchbooks to reveal fascinating dioramas of futuristic architecture, a map of a building complex that resembles a Jetsons-meets-Sun Ra fantasia of — irony of all ironies — the Crenshaw Hills mall.

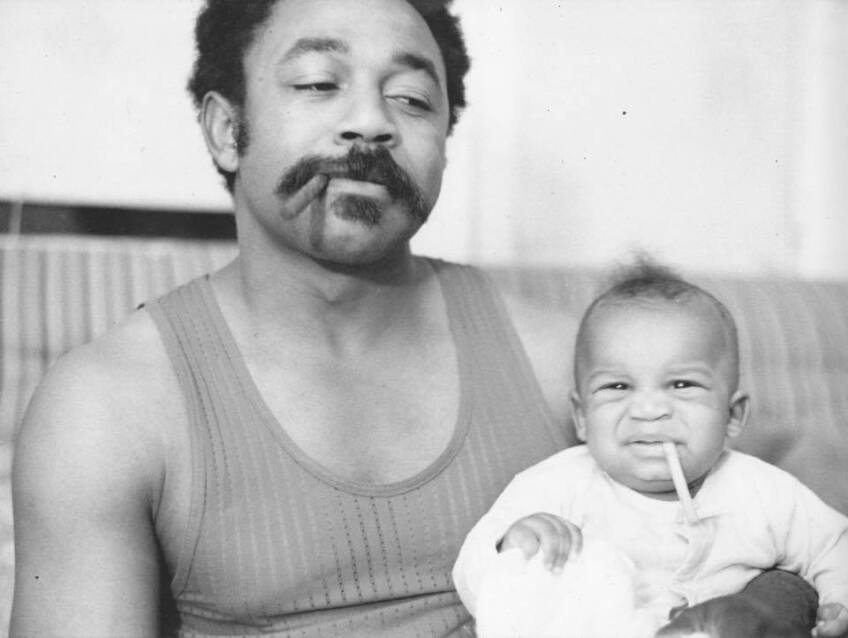

Top Image: Chephren Rasika and his daughter in his father's garage in South L.A. | Stefani Urmas