Connecting the Dots: Oxy Arts Exhibition Links Moments of Asian American Activism, Art and Collectives Throughout History

You may be familiar with the local zine turned internationally distributed "Asian pop culture and beyond" magazine Giant Robot, first published in 1994 by friends and UCLA graduates Eric Nakamura and Martin Wong. But you may not know about the 1969 UCLA student-run newspaper Gidra that inspired the two. You may have seen mainstream media coverage about the multigenerational activist sewing group Auntie Sewing Squad — an 800-plus-member national network that started in the Koreatown living room of performer and now Pulitzer Prize finalist Kristina Wong in early 2020 to address the nation's lack of PPE during the pandemic. Or seen articles about Stop DiscriminAsian — a collective of East, Southeast and South Asian arts workers formed the same year in response the wave of anti-Asian attacks that dramatically increased during the pandemic. But perhaps the work of Basement Workshop — an Asian American collective of artists and activists that produced the notable quarterly Bridge Magazine and the seminal 1972 arts book Yellow Pearl — may have slipped through your radar. There was also Godzilla — a New York–based group of artists and art workers in the early '90s who worked to increase Asian American representation in major art spaces and mainstream media through open letters, a nationally distributed newsletter and themed exhibits.

"Voice a Wild Dream: Moments in Asian American Art and Activism, 1968–2022," an exhibition on view at Oxy Arts in Northeast Los Angeles through Nov. 18, brings together these early Asian American publications and collectives back into the public eye. The exhibition highlights the important role of each in documenting the Asian American experience and providing platforms for Asian American voices and creativity when there weren't any. The exhibition also serves to explore the interconnected nature of each collective's work and how one action ripples through time, inspiring another. Through the early groups' archives (publications, photography, artwork and ephemera) and the multimedia work of collectives active today (videos, a palm-sized zine, a community-generated quilt and sound recordings), the show is evidence that the so-called "silent minority" has been resisting, disrupting and transforming the status quo for decades through grassroots and intergenerational art production and activism.

Curator Kris Kuramitsu says those featured in the exhibition are "artists and culture workers who are committed to kind of moving the needle forward and spreading some idea or trying to realize a different kind of world in whatever way that they're doing." For these groups, art was "a way to enact a different kind of future — not just as a vehicle for communication." The viral Los Angeles Public Library performance of "Racist, Sexist Boy" by the all-girl rock band The Linda Lindas and their sets at the Save Music in Chinatown shows at Grand Star Jazz Club to raise money for a school's music program are examples of this and the intergenerational thread that is now powering such movements. The daughter of Giant Robot and Save Music in Chinatown co-founder Martin Wong, Eloise and her cousins Lucia and Mila de la Garza are three-fourths of the group.

"Voice a Wild Dream" touches upon a mere fraction of a history that unfortunately is largely unknown or not easily accessible to the larger Asian American community and beyond. Kuramitsu, who is currently senior curator at large at The Mistake Room and adjunct professor of art history at Harvey Mudd College, says the exhibit came about through conversations with artists and colleagues who realized that younger generations were very eager to learn more about their activist predecessors. "Since the beginning of the pandemic, these conversations have gotten much more urgent with the rise in anti-Asian hate and violence, which, of course, was always there. But I think there was an increase in an awareness [of past Asian American activism] and the pandemic allowed the dots to get connected."

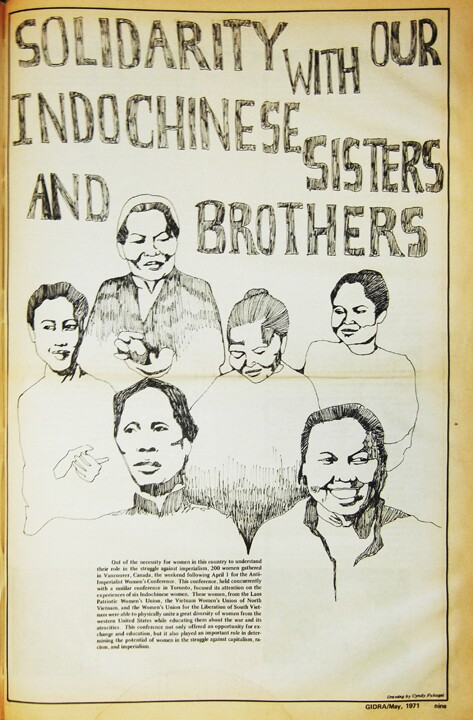

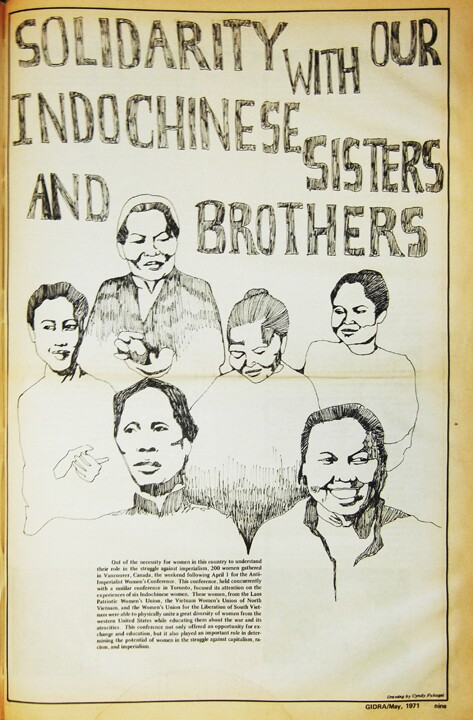

Decades before, it was the Black liberation movement and antiwar movement of the 1960s that spurred Gidra co-founder Mike Murase and a dozen other student collaborators to publish their community-oriented, activist newspaper: "We wanted to be a part of the struggles for social change," said Murase. Their headlines included "The Third World: A Response to Oppression" and provocative cover illustrations by emerging Asian American artists, such as an alert woman sitting on the floor, cradling her breastfeeding newborn in her right hand, while clutching a semiautomatic rifle in her left. Prior to its publication, Murase was among the UCLA students together with faculty, alumni and community to bring ethnic studies courses and an Asian American Studies Center to UCLA. But for him and his classmates, the university needed to do more.

They pushed for funding for a publication just as the Black and Latino students on campus had. "We argued that an institution of higher learning had the responsibility to teach its students not only the ideas of the dominant society," he shares, "but the ideas of the many cultures and many histories that make up America." The university would only fund it if they had editorial oversight, which was a deal breaker for them, so they started their own. "We began raising money and recruiting volunteers to work on the publication," recalls Murase, who emphasizes the gravity of the situation for everyone involved. "We were hungry to learn about our own history." And on March 31, 1969, the maiden four-page issue was published.

"As we organized young people, we learned that there was a deeply felt desire to express ourselves in poetry, art and writings. We wanted to find our own voice." And, perhaps more importantly, lasting relationships and impacts resulted in the process. "In the crucible of a movement for social justice or class struggle, if you will, we discuss, we argue, we develop a deeper sense of unity and camaraderie," he adds. "And when an idea or feeling is put down in print, they have a broader reach and a lasting impact beyond our own experiences."

On the East Coast, the following year, Basement Workshop was founded in New York's Chinatown, and were "primarily Chinese American artists who were involved in all kinds of [creative] community workshops, health fairs and voter registration drives, and they had a really active print workshop," says Kiramitsu. Photographer Corky Lee was active there and many Asian American writers and playwrights who would later rise to national prominence, such as Jessica Hagedorn and Frank Chin, participated in their workshops. "Ultimately, Basement Workshop sort of birthed all these other organizations, many of them are still active, including the Asian American Arts Centre."

Among Basement Workshop's most active members was artist Tomie Arai, who produced illustrations for the "Yellow Pearl" book and painted murals in the city depicting Asian American life and struggles. The work of the intergenerational cultural collective she cofounded in 2015, Chinatown Art Brigade, whose mission is to advance social change through various modes of production, is also featured in the Oxy Arts exhibit. The intergenerational aspect of the Brigade, she notes, has been vital to realizing their goals. "I've learned so much from younger activists and I'm continually inspired by their passion and commitment. As I see it, the purpose of upholding intergenerational models like the Brigade centers around access and shared principles of equity and inclusion," says the 73-year-old who is currently an Artist in Residence at the Asian American women-led CAAAV: Organizing Asian Communities in New York. "We are working intentionally to generate some kind of consensus around ways to build a movement. … The difficult challenge I see before us is our capacity to address ableism and ageism, provide collective access and recognize the need to shift our priorities, post-COVID 19, toward building a more inclusive and compassionate future." She's a source of inspiration for those of different generations, first because of her work through Basement Workshop, and more recently, because of CAAAV and the Brigade. Not one to take a break, Arai actually just started a full-time job through the artist employment program Creatives Rebuild New York and spends her weekends mobilizing tenants to fight gentrification.

At the Oxy Arts show, a corner displays the ongoing work of Stop DiscriminAsian, which mobilizes, inspires and empowers Asian Americans and allies through open letters, social posts (Virus Don't Discriminate Neither Do We is among them), and panel discussions, to name a few. The group, which consists of six to two dozen active members at a time, calls out anti-Asian racism and xenophobia in the art world and emphasizes the global influence of Asian culture, among other important issues and struggles. They declined to call out specific member contributions, but instead shared this: "We are artists, writers, educators, and organizers who continue to consider how we can creatively use our skills and resources rooted in the arts towards social transformation, and how we can best make use of our platforms, which include our respective art communities who we often bring together in coalition."

Murase, who like Arai is in his 70s, would likely be emboldened by such movements and emphasizes the need for Asian Americans of all generations to push ahead: "Fifty years since Gidra stopped publishing, and yet so much more to be done and said. We cannot stop," he says. "Hard work is a part of the equation. We build relationships through solidarity work to gather forces for a bigger fight, for a better tomorrow."